The wild boar broke from the forest intent on sharing some of its pain. Bloodied and bristling with rage, it fixated on Sabine Eriksson, a hunter from Sweden.

From my position 300 yards down the line I heard murderous bawling and yapping, screaming and snapping, fury and frenetic gunfire—but there was nothing to be done except nervously hold the line and keep my rifle at the ready. Meanwhile Sabine fired her Merkel into the boar’s face as she parried behind a tree, pinballing it in another hunter’s direction. More hounds joined the melee, stupidly snapping at ham and jowl only to be flung off like fleas. Additional shots echoed until eventually the macabre music of the chase faded from the Bulgarian countryside like the sunset of communism.

That evening back at Byalka lodge near Lovech, Bulgaria—the former hunting ground headquarters of that country’s former head of state—the day’s slain boars were laid out in rows and encircled by a ring of torches in a ceremony of celebration. Sabine recounted the story and vodka was passed cordially between houndsman and hunter. Included were Bulgarian hunters, a couple crazy Russians, a few Swedes, Norwegians, some fast-firing Finns, an Australian and me, the sole American.

Most of these hunters were adept at shooting driven game, the preferred way to hunt wild boars, moose and stags in Europe. Me? Not so much. Previously I’d viewed driven hunts as a nobleman’s idea of shooting game for fun without dirtying the hands. But I soon found that’s not the case. Driven hunts are employed because they are the most effective way to roust stubborn old boars from thick cover. And it’s far from foolproof. Boars are savvy, dogs tire and hunters miss. After three days of hunting, I’d yet to fire a shot. But this style of hunting is a team effort, rich in camaraderie, where all participants celebrate in the kill.

Indeed, hunting doesn’t get much more exciting than a driven wild boar hunt in unfamiliar country. When large, tenacious game is pushed to desperation, anything can happen. Maybe nothing happens at all save the sounds of hounds, but you must remain prepared to make a safe and accurate shot in a second’s notice, for these boars are not mere feral swine. They’re true Russian wild boars with giant shoulders, long legs and wicked ivories, and they’ve been persecuted for centuries by kings and farmers alike. If you see one it’s normally a blur of black streaking through the trees. Many Americans learn the toughest part is firing at all, because we want the animal to stop so the shot can be perfect. But if you hesitate, the opportunity—and the boar—is lost.

On the final evening of the hunt, with gunfire and barks echoing all around, a single black boar broke from timber. I waited two seconds until it cleared Sabine to my left, then I swung the rifle, placed the glowing red dot of the Aimpoint on the boar’s shoulder and pulled the trigger. A moment later there was nothing; the boar had vanished into vegetation. At sunset, after the din of dogs had died down, I walked over. There was my Bulgarian boar, pure black and perfectly dead from a Norma bullet behind the shoulder. Back at the lodge my new European friends congratulated me on a fine trophy and a great shot. I believe they were truly impressed. Me? Not so much. I knew it was mostly luck, but I kept that to myself as they passed the vodka.

No doubt some readers will object to the shooting technique described in this article. It’s as though we’ve forgotten the lean years in this country’s history when shooting at running game was a standard and necessary practice for sportsmen who desired to eat well and regularly. In some parts it’s still practiced: Ask any Deep South hound hunter or Pennsylvania deer driver how many deer he’s shot as they stood statue-still. But during the surplus years—and probably due to two or three generations of “riflemen” who only practice by shooting stationary targets from benchrests—American hunters have lost the art of shooting running game. In Europe, however, where sportsmen hunt driven deer and wild boars with the same enthusiasm and success that you and I enjoy as we ambush them from treestands, the art flourishes. Indeed, if you don’t shoot at running boars in Bulgaria, well then good sir, you’re not apt to shoot many boars. Here’s how it’s done.

1. Gather data.

Like any good shotgunner, the key to hitting running game is not to shoot where the animal is, but to anticipate and shoot to where it will be. Luckily, each of us comes equipped with an amazing game predictor: It’s called our brain. You simply must let your brain gather data via the eyes. It will immediately calculate the animal’s speed and direction relative to you. This means keeping both eyes open and not obstructing input by shouldering the rifle too early. So, when you first see a running animal, keep both eyes open with your rifle held below your eyes while you begin the following sequence.

2. Move your feet.

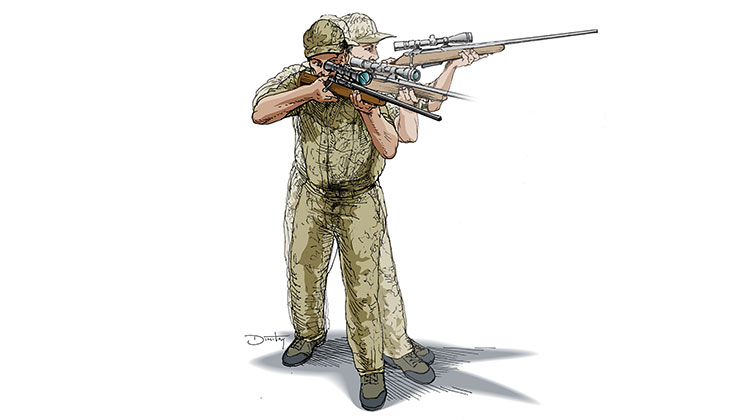

With your eyes glued on the animal, move your feet so your body comes into an athletic-style stance from which you can lean forward to drive the gun barrel and stay on balance as its recoil rocks you backward. Place your lead foot slightly ahead of the running animal and twist at the waist as you begin slowly swinging the rifle at the animal’s pace.

3. Mount and swing the rifle.

Just as you find your footing, begin raising your optic (or sights) to your eye as you move the barrel laterally with the boar. Don’t think of it as shouldering your rifle, as that will come naturally. You should see the game in your scope before your shoulder and cheek touch the stock. This means that you must raise the rifle to your cheek so that it lifts with buttstock and barrel more or less level.

As the gun rises, work the safety. The hands should smoothly pull the rifle up and push it a few inches away from the shoulder so the buttstock clears clothing before snugging it back into the shoulder pocket. All the while, the dominant eye should be directing the hands to move the gun barrel so the reticle finds the lead edge of the animal.

4. Aim small and rough.

Focus on a specific, small point on the sternum or lead shoulder (for broadside shots) and do your best to put the crosshair on it and keep it there. Unlike a shotgun that should be pointed, a rifle with its single projectile must be aimed. The key is to learn to relax and not worry about being so perfect that the swing stops. Realize that you’ll never get the reticle perfectly steady on your intended aiming point. Get it close, in line with the animal’s body, and (if the distance is less than 100 yards) don’t shoot if you see daylight between the reticle and the animal. For straightaway shots, aim for the base of the tail or a hip if quartering away.

5. Squeeze the trigger.

Don’t mash the trigger but concentrate on pressing it back smoothly as you swing your barrel so it doesn’t disrupt the swing’s plane.

6. Follow through.

Make a conscious effort to continue the barrel’s swing along with the animal’s path after you pull the trigger. While a good follow through will ensure hits, it will keep you in position to make a follow-up shot if you miss.

7. Work the action and reposition your feet if necessary.

The support hand is used not only to support the weight of the rifle and guide the barrel, but also to apply rearward pressure to keep the rifle in the shoulder pocket so the trigger hand can work the bolt. While maintaining your cheekweld on the stock, work the bolt as you recover from recoil. Once fully recovered, find the target in the sights and rotate your feet if you are near the limit of your waist’s rotation. Keep swinging with the target and shoot again. Repeat as necessary.