Mention wildlife conservation to folks on the street and they may think of endangered species like the giant panda or black rhino. But fish and wildlife in your local community also require and benefit from conservation. State and federal governments as well as nonprofit organizations all help to conserve fish and wildlife in the United States by following a set of principles called the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation.

While many species of fish and wildlife are doing very well in the United States, some are not. Even though government and private partners are working to conserve species in trouble, there was actually a time not too long ago when many species were in bad shape. Certain animals that are common today, including waterfowl, alligators, whitetail deer and bald eagles, suffered in the past from overhunting and habitat loss. Until the late 1800s, people just assumed Mother Nature would take care of herself, and that her bounty was endless. This was the pioneer, tame-the-wilderness mindset rooted in the dawn of the European colonization of North America. Further, people saw fish, wildlife, trees, minerals and other natural resources simply as raw materials that could be used for personal economic gain. Very few people thought fish and wildlife might be limited resources.

So what inspired change? For one, the slaughter through unlimited hunting of species like the bison and passenger pigeon, the latter to the point of extinction, struck a nerve with the public. Self-serving people saw many game species as a resource to be exploited and turned into cash. Another contributing factor to such losses was the fashion industry, where fancy feathers for ladies’ hats took a toll on bird populations. Other catalysts for change were the grandeur of Yosemite Valley and other iconic American places, the efforts of Scottish naturalist John Muir and laws promoted by President Theodore Roosevelt, all of which helped to bring the idea of wildlife conservation into national focus.

In the late 1800s, Roosevelt and fellow conservationists began to push for federal legislation to protect wildlife. Beginning in the 20th century, Congress passed such laws as the Lacey Act (prohibits illegal trade in wildlife, fish and plants), the Migratory Bird Treaty Act and the Endangered Species Act. Around the same time that Congress passed the Lacey Act, states responded to concerns raised by overhunting with new game laws and the appointment of the first game wardens.

This infant system of state regulation of wildlife grew into what is today the 50 state fish-and-wildlife agencies that conserve fish and wildlife for the public. These agencies have the legal authority needed to conserve species. They, along with federal and private partners, have enjoyed many conservation successes including a partnership that allowed the American alligator to rebound strongly from the brink of extinction. Today, the alligator is so abundant that it can be legally hunted in many states.

While the laws and partnerships that enabled successes like the American alligator’s rebound do not effectively address the “why” or the policy considerations behind such successes, the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation does. First described in the mid-1990s by wildlife biologist Valerius Geist, the Model describes in plain words the principles that underlie conservation decisions in the United States and Canada.

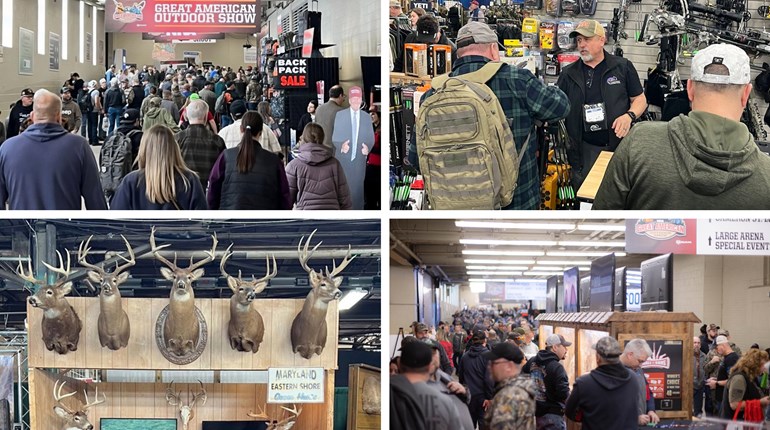

Today’s sportsmen pay for the preservation and management of our wild lands each time they purchase hunting or fishing licenses; equipment for hunting, shooting or fishing; or a day pass to a public park. Through grassroots participation and our votes, as well as financially supporting conservation, we help to ensure wildlife continues to be a public trust resource in perpetuity—a tenet of the Model.

The everyday efforts of hunters, sportsmen, campers and sport shooters strengthen language in state laws, increase the focus on holistic wildlife management and promote young children’s understanding of the importance of wildlife conservation.

For example, the NRA Women’s Policies Committee established the Women’s Wildlife Management/Conservation Scholarship that is administered by The NRA Foundation. This scholarship is a renewable, one-year, $1,000 scholarship available to full-time college juniors or seniors.

7 Pillars

The Model is founded on two basic tenets: taking of wildlife is reserved for the non-commercial use of individual hunters; and fish and wildlife are to be managed so that their populations persist forever. It is based on seven pillars.

1. Wildlife as a Public Trust Resource—Martin v. Waddell, an 1842 U.S. Supreme Court case, established the legal precedent that it is the government’s responsibility to hold fish and wildlife in trust for all citizens, and that private individuals cannot own fish and wildlife. This is the principle component of the Model.

2. Prohibitions on Commerce—Hunters and anglers led the effort to eliminate markets and commercial traffic in dead animal parts, which was a huge business in the latter half of the 1800s and early 1900s. The market killing of birds and animals decimated many species and brought some species to or near extinction. Today, this principle limits privatization of the public’s fish and wildlife and helps prevent overexploitation.

3. Hunting Opportunity for All—In the United States and Canada, every man and woman has a fair and equal opportunity under the law to participate in hunting and fishing. No single group of hunters or non-hunters can legally exclude others from the opportunity to pursue game.

4. Non-frivolous Use of Wildlife—Although laws govern access to wildlife and ensure that all citizens have a say in its protection, some guidelines on take are needed. Non-frivolous use serves as this guideline and strives to ensure wildlife is not killed simply for its horns, antlers or feathers.

5. Wildlife is Considered an International Resource—The boundaries of states and nations are of little relevance to migratory wildlife and fish, and policies and laws for wildlife conservation have to address this reality. The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 is an excellent example of successful international cooperation.

6. Scientific Management—The original public push for conservation came primarily as a reaction to the decimation of many species. States began to appoint game wardens and set up commissions in the early 1900s, and these officials were tasked with making and carrying out conservation policy. However, they needed information to inform their decisions. Aldo Leopold’s inauguration of science-based conservation policy in the 1930s grew into the science-based conservation systems we have in place today.

7. Democratic Rule of Law—Wildlife is allocated for use by citizens through laws. This protects against allocation by other criteria, such as elite social status (as occurred in Europe), on the basis of land ownership or by market principles. All citizens, through their elected representatives, can have input into how fish and wildlife resources are managed and allocated.

Editor’s Note: This article was inspired by a lecture from, and written with the guidance of, Carol Bambery. As an avid shooter, hunter and Second Amendment activist, Bambery is General Counsel to the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies, Washington, D.C. A member of the NRA Board of Directors since 1998, she has served on several committees including presiding as Chair for Bylaws and Resolutions, and Vice Chair for Women’s Policies and the NRA Civil Rights Defense Fund. Bambery is a trustee of the NRA Whittington Center and chairs the NRA National Firearms Law Seminar, which annually educates hundreds of pro-gun attorneys.