The birds were already flying when we started setting up, their whistling wings taunting us from overhead as we climbed from the boat and distributed the decoys around the layout blinds we’d be calling home for the next four or so hours. We worked quickly, laying a trap we hoped would fool the local diver ducks. Temperatures were unseasonably warm for Utah in mid-December, though that seemed the case throughout the country. Nothing we could do about it. At that moment, though, it remained of particular concern to me, because all that was supporting my rather large frame was a few inches of softer-than-usual ice—and it wasn’t long before, with a sickening, dull crack, the frozen surface beneath me gave way and dumped my rear end right into Willard Spur. Oh, I was okay—the water was only a couple of feet deep, and I’d come equipped with waders—though my heart certainly skipped a beat. With a sigh, I stood up, put my bare hands on the sturdiest looking piece of ice I could find and lifted myself back up, to resume my decoy duties. I’d remember what my feet felt like later. We had ducks to kill.

■■■

Waterfowl hunters are a dedicated breed. The long hours, the gear costs, the weather patterns—on the days most big-game guys would decide to take a break, there are duck hunters that are just starting to get excited—all make for a package that’s not fit for everyone. Waterfowl hunters do it for different reasons. Sure, lots of guys have birds mounted on their walls, but they aren’t true “trophy” animals. And you’ve got to shoot a pile of birds if you’re looking to feed a family of more than one. But the diehard bird hunter will chase his prey clear across the country, if he has to. Each of the North American flyways (Pacific, Central, Mississippi, Atlantic) offers its own local terrain, unique challenges, homegrown traditions and particular selection of birds. So, for any waterfowl hunter, the thought of hitting all four in a calendar season is bucket-list worthy. Me? I’ve already finished my tour. Here’s the road map I followed, in chronological order.

Stop 1: Central Flyway

Flyway Includes: Montana, Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota and North Dakota, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories*

Dates: September 2015

Location: Yorkton, Saskatchewan

Targets: Ducks, Geese, Sandhill Cranes

*According to Delta Waterfowl

My 2015 season began a little earlier than it normally would, courtesy of a trip to the Great White North, which I covered in detail earlier this year in American Hunter (“Crane Games,” October). It wasn’t my first trip to the absolutely massive (more than a million square miles across the continent’s interior) Central Flyway, but it was the first time I’d visited so early in the year. Not that beginning the season in Saskatchewan, a true waterfowl Mecca, is a bad thing. Though we’d journeyed north with eyes on knocking down plenty of ducks and maybe a few geese with outfitter Habitat Flats, we were caught a bit by surprise by the sandhill crane. As I’ve mentioned, weather patterns were a bit wonky throughout all four flyways last year, and, as a result, there were still cranes moving through eastern Saskatchewan come late September. We made sure our share of them didn’t get any farther south, if you catch my drift.

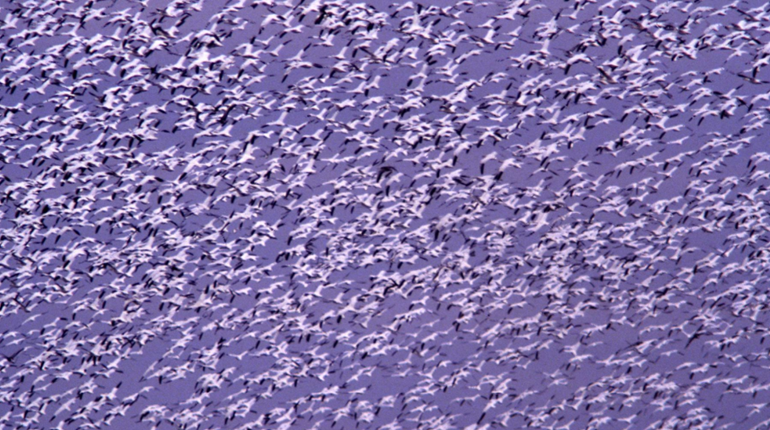

When I call Saskatchewan a waterfowler’s paradise, I mean it. Those of you who have been need no explanation. Those of you who haven’t should be booking your trips before you finish reading this story. (Go ahead, put the magazine down and do what you’ve got to do. I’ll wait.) Known for its endless waves of birds and generous bag limits, Canada as a whole is a must-visit destination for any bird hunter. It’s nice to get on the migration before half the flock has been educated, too. You’ll hunt predominantly in fields of peas and barley, and results shouldn’t be an issue. We did the Central Flyway proud during our stay, knocking down continual limits of ducks and cranes alike. The geese weren’t quite ready to cooperate—I’m told they started moving a bit more after we left, though we did kill a couple of honkers. The ducks, largely mallards and teal, still hadn’t quite molted into their full plumage yet. So don’t go thinking we were just stacking up hens in the photos. Long story short, I kicked off my year, and my tour, right.

Stop 2: Pacific Flyway

Flyway Includes: Alaska, Arizona, California, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and those portions of Colorado, Montana, New Mexico and Wyoming west of the Continental Divide*

Dates: December 2015

Location: Great Salt Lake Region, Utah

Targets: Ducks

*According to Delta Waterfowl

The second leg of my journey took me to Utah’s Great Salt Lake, where I had the misadventure detailed at the beginning of this story. The Pacific Flyway is easily the single most diverse of the bunch, featuring environments that range from the Rocky Mountains to the shores of the Pacific Ocean. I found myself positioned on the eastern portion of the flyway, where I’d join Avery pro-staffer Chad Yamane for a pair of hunts on and around the famous Great Salt Lake. Due to its incredible salinity levels (certain portions are reportedly 10 times saltier than ocean water) nothing lives in the lake, short of brine shrimp. The thing is, the local waterfowl population enjoys eating brine shrimp—which makes it a fantastic place to kill birds, if you’ve got the equipment required to do it.

I say that because the lake and the surrounding bodies of water tend to come one of two ways during waterfowl season: incredibly shallow, or frozen. It’s why so many of the local hunters have adopted airboats, which ferry them over sheets of ice and occasional 5- to 6-inch waters alike. It’s with an airboat that we were able to reach a hole in the ice near what’s known as Willard Spur. The Spur sits north of the Great Salt Lake proper, but remains connected to the lake’s overall ecosystem. Because the Spur gets some freshwater inflow from the nearby Bear River, its salinity level is somewhat unique within the context of the lake’s territory. As a result, it’s not a bad spot to find a hole in the ice and set up for diver ducks that are returning to freshwater after feasting on brine shrimp. It was there that we stacked up a healthy pile of common goldeneyes. Known as such because of its distinctive iris, the goldeneye is a tough, fast-moving diving duck that’s no easy target. Though flocks are relatively quiet on the approach, it’s easy to hear the unmistakable whistling of their wings as they lock up and prepare to land. On more than one occasion, we heard them coming down on us before we saw them.

Day two consisted of a more traditional hunt on the Great Salt Lake proper. The recipe? All black silhouettes (some of which just barely resembled what I’d call a duck) and black coffin-style layouts, all in just a few inches of water. The result? A three-man limit of birds made up entirely of teal and spoonbills. Yeah, we piled up the spoonies. Don’t judge us.

Stop 3: Mississippi Flyway

Flyway Includes: Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, Tennessee and Wisconsin, and the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario*

Dates: December 2015

Location: Jonesville, La.

Targets: Ducks

*According to Delta Waterfowl

Named for the legendary river that runs clear through it, the Mississippi Flyway is the continent’s most heavily utilized migration corridor for waterfowl. In my case, visiting it meant venturing to Louisiana, which has no shortage of duck hunters. The most famous ones may carry the last name Robertson, but they’re far from the only locals who have feathers on the brain. Our hunting grounds had a reputation all their own. Known for its plentiful waterfowl population—not to mention its TV show on the Pursuit Channel—Honey Brake is something of an institution. Honey Brake and other destinations in the region like it have often been around for decades, and have the property—and corresponding blind layouts—to prove it. Some of Honey Brake’s duck blinds would be more properly described as duck mansions. Complete with a garage to park the boat in upon arrival. Honey Brake as a whole is home to 120 duck blinds, and sits conveniently near both the mighty Mississippi and Catahoula Lake, a 60,000-acre waterfowl wintering grounds. So, going in, it felt like a slam dunk.

Well, not quite. Creature comforts aside, we were vexed by two unfortunate truths in Louisiana. First and foremost—this’ll sound familiar—it was simply too warm. Fresh birds just weren’t moving south. There was no need for them to, really. So while we saw no shortage of birds, they were stale and very familiar with our setups. Second, Louisiana is at one of the southernmost points of the country. By the time a migrating duck gets down there, he’s been shot at by every Tom, Dick and Harry in the flyway. So the birds we were dealing with were stale and educated. They may as well have had Ph.D.’s.

Still, we did work where we could, and took advantage of the region’s sheer diversity. By the end of the trip, our collective group of hunters had bagged a healthy quota of mallards, plus a few teal, wigeons, pintails, ring-necks and canvasbacks.

Stop 4: Atlantic Flyway

Flyway Includes: Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Vermont, Virginia and West Virginia; the Canadian territory of Nunavut and provinces of Newfoundland, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Prince Edward Island and Quebec; plus the U.S. territories of Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands*

Dates: January 2016

Location: Chestertown, Md.

Targets: Ducks and Geese

*According to Delta Waterfowl

It’s probably blasphemous that my home flyway wound up being the final stop in my tour, but schedules can get cramped when you’re trying to put together a Waterfowl World Tour, of sorts. Truth be told, I’d very briefly hit the Atlantic Flyway in November 2015, but I’d gotten skunked. So I decided to give it a second go once the calendar rolled over to 2016, with hopes of killing a few birds before the calendar season came and went.

The stage was set. We were in Chestertown, Md., a waterfowler’s dream. Our hunting grounds were mere miles from the Chesapeake Bay and all of its duck-slaying lore. We hunted alongside my father, Pat Skipper, a man who’d spent decades killing ducks and geese up and down the state. How could we miss?

Thing is, the Atlantic Flyway had a really rough 2015-2016 season. It may have been hit the hardest by the oddball winter weather. Temperatures remained warm well into January, and snowfall simply came too late. Though the flyway had no shortage of birds, they spent much of the hunting season harboring in northern New York and Canada. But dammit, we had to try. Which is how we spent three mornings and two evenings watching stale birds essentially shrug with disinterest at our decoy spreads and ignore our calls. We couldn’t even get lone geese—birds that, in countless years past, in those very pit blinds, I’d watched come right to the gun—to work for us. We did eventually kill two Canada geese—though not on the same day—before throwing our hands up in defeat. As Dad noted, numerous times, “Another season like this and I may have to become a deer hunter.”

It was that kind of year in the Atlantic.

Still, though, we’d hunted the flyway. The two geese, they were just a bonus. What had started in mid-September finally came to fruition in mid-January. Four flyways in one season. This one, at least, I can scratch off my list.