I knew I had messed up as soon as we left the blind. We stepped out to a wind speed that had increased significantly without my notice. We had been sitting for hours in this blind with the door and windows shut to keep in the sparse heat and to mitigate any scent we were sending off to adventure on the wind currents. Iowa winters can be stormy, and the wind had been rocking and buffeting us for days. We were trying to stay mobile with the unpredictable behavior of rutting bucks, but the wind had driven us behind the walls of various portable and permanent blinds.

This wind had already cost me one of the best 8-point bucks I have ever seen wild and free. He showed up the previous day just before dark and started feeding on some sparse standing corn, just a little bit too far off for a shotgun. That’s the curse of hunting open land with restricted firearms. You will see a lot of deer that you should not shoot at; it’s a constant battle between temptation and your conscience.

After a while, the 8-point started closing the gap so slowly I thought my head would explode. As very last shooting light approached he passed my mental marker for the longest distance I would shoot. I had fired a lot of slugs off the bench out to this distance and beyond. I knew all the ballistics, except one: the wind, which was running high. I tried to time the gusts so I could shoot in a lull. I wracked my brain to come up with a hold to shoot in the wind. I did everything except give into a panicked, Hail Mary shot, which is always tempting but is a paver on the road to disaster. It was just too far to risk it. Finally, the buck saw something he liked and faded back into the wood line. The disappointment grabbed my psyche and shook it like a worn-out rag doll.

I remember years ago during an interview for some long forgotten article I was writing when a game warden had told me: “The ethics of the situation are often determined by the size of the antlers.” This buck was enough to inspire a bishop to risk damnation. The rest of the night I was second-guessing myself so hard that my mind all but seized a bearing.

The next afternoon we were back in the same blind and night was coming fast. The 8-point didn’t show, but a big, wide and very even 10-point did. It quickly became a bird-in-the-hand situation. We watched him for a long time as he moved closer and closer. My plan was to let him get as close as possible before shooting, but a doe wrecked it all. He decided to follow her, and it was clear that he was as close as he was going to get. He stopped, quartering to me more than I wanted, and it was now or never. I held for the wind and distance and executed a perfect trigger pull.

Shotguns kick, there is no getting around that, and I lost sight of the deer for a brief time. When I found him again he was just going over a hill and looking rough. As Mike Mattly and I gathered our gear I had all the confidence in the world. Then we stepped out and that first wind gust told me I had screwed up.

It had been buffeting the blind with almost a musical pattern that became monotonous over time, and I didn’t notice the gradual increase in speed as the day cooled with the long sun. My mistake.

I had just made a shot on that big 10-point that I can do in my sleep if I have all my information correct. But that’s the problem when you start stretching the hunting distance with any firearm: the fine print gets a say. You must be aware and adjust for the small and subtle things that don’t factor in at the range. I felt sick as we started off in the gathering dusk to look for a blood trail.

It’s well known in outdoor-writing circles (and likely outdoor-reading circles, too) that we writers never miss. This is the point where traditionally the writer goes over the hill to discover that he has made a perfect shot after all and the buck of a lifetime is waiting patiently to pose for the hero photos.

But I told myself when I started this career I would never intentionally lie to my readers. Of course, I could just gloss over what happened next and tell you I found the deer and make myself out the hero, but this article is about the fine print and how we must be aware of it at all times. It’s an important lesson, and I can convey it by admitting I am human, just like every other hunter in the world. Sometimes things don’t go according to plan; I’ll take the hit. The other lesson I hope I can convey is one of responsibility: When things go off the rails, it’s on you to fix it.

The firearm you are using is not the issue. Long range is long range. While a shotgun might enter long-range territory at less than half the distance for a rifle, the fine print can still trip you up.

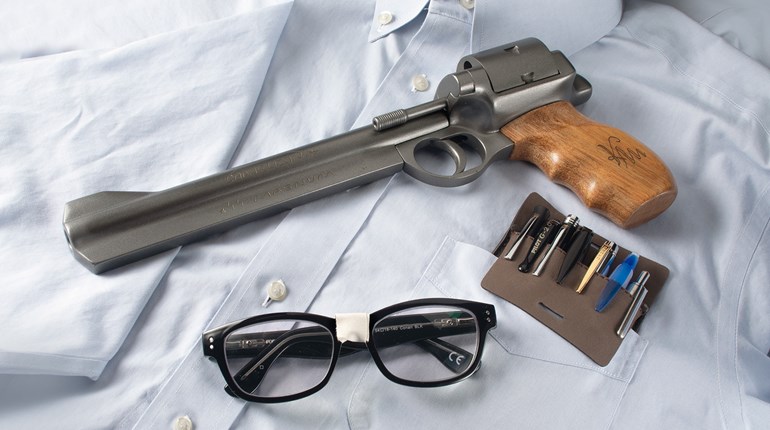

Before I headed to Iowa I took my Savage Model 212 shotgun and a bunch of Federal Premium Trophy Copper slugs to the range several times. I was using a Bushnell Trophy riflescope with a DOA 250 MZ ballistic reticle and shot on targets from up close to long range, all to fine-tune the holds at each distance. This is pretty much what you would do with any firearm that you might use for a longer shot.

I entered my Iowa hunting blind with a self-imposed limit of how far I would shoot, and that number was a fraction of the distance at which I could hit a target under controlled conditions at the range. As this story illustrates, even with the discipline to stick with self-imposed limits, Murphy lives and things can still go wrong.

The fine print is nothing more than the differences that occur once your target changes from paper or steel to flesh and blood. It’s the things you may or may not remember and probably can’t control. The wind, the light, the rest for your gun, the posture of the deer, your heart rate and your emotions. These are all the fine print factors that change the rules of engagement when hunting. Ignore them at your peril. What the fine print means is that although you may be slamming steel in the next ZIP code when you are at the range, to stay ethical you really need to dial it back a lot when you are hunting.

The thing is, if the deer had been broadside it would not have mattered so much. The margin of error I like to allow would have still put the slug in the kill zone. But the deer was quartering to me, and this is one of the fine print factors that wreaks more havoc than most hunters understand. Sure, if you place the bullet with precision it’s a deadly shot. But trigonometry comes into play here and the margin of error becomes substantially smaller as the angle of the deer’s posture increases. Depending on the angle of the deer, a bullet that’s off the mark even a little bit will hit much farther back than it would on a broadside deer. A shot that might catch the back of the lungs on a broadside deer can go into the badlands on a quartering deer. That’s what happened to me.

The deer didn’t go far, in fact I found him just over the hill, lying in the high CRP grass and watching us. The fact he didn’t travel far before lying down and that he still had his head up and he was alert indicates a gut shot. The best thing to do is back out of there, come back in the morning and he will be lying dead in that same bed.

I didn’t do it. Part of that was stupid ego; I wanted him in the truck that night. Part of that was also my anguish over what I was putting him through. I caused this; I needed to end it. I thought I could.

I won’t bore you or torment myself with the details, but my plan didn’t work out and he made it across a fence onto property we didn’t have permission to enter. I watched him through my binocular until dark. I knew his problems would be over soon, so we left to find the landowner and get permission to go after the buck in the morning.

This buck had a very distinctive rack, it was wide, even, tall and very white. At full morning light Mike and I were crossing the fence when Mike spotted a doe running through an opening in the trees. Right behind her was my buck. How was that even possible? Did I miss? Maybe he was just tired and wanted to lie down? I didn’t believe that, but the deer chasing that doe was him. Was he unhurt, or such a stud that even with a bullet wound he was trying to breed? Nothing made sense, but our eyes saw what they saw.

We were moving silently along the fencerow, trying to find him when the big 8-point from two days prior stood up in the CRP grass, 50 yards from us and completely unaware we were even on the same planet.

He was magnificent, thick, unbelievably heavy and tall. His brow tines were perhaps the longest I have ever seen on a wild deer. We had every evidence that the buck I thought I was going to recover this morning was still alive, so in theory that made my tag valid. In front of me was a world-class whitetail, one that I had been hunting for 50 years. It would have been so easy to shoot him and call it good. I suppose a lot of people could have made that work with their conscience. Lord knows I tried. He stood there for a long time, five, 10, 16 minutes? I can’t say. Time gets all goofy in these situations. So do your emotions. In the end, I was confident in my shooting and understood the fine print and its effect on my shot. I knew in my heart of hearts where I hit that buck the night before, and so I watched the buck of two lifetimes just walk away.

Mike Mattly and I have hunted together for a couple of decades and in a few dozen places. He has the best eyes for spotting game I have ever encountered, and we were on his home turf. So when he froze, so did I. A doe ran up the hill and behind her was my buck. Perhaps 100 yards away, he stopped broadside and looked at us. I eased up my shotgun for the shot, but I didn’t take it. My rule of thumb in a situation like this is to shoot fast. I think the best hunters are very decisive and never hesitate. I hesitated.

Maybe it was just the weirdness of this thing. I knew that deer could not be alive, yet he was. I also never look at the antlers once I decide to shoot a deer. You know you are going to shoot, no point in ever allowing yourself to be distracted from the job of making the shot. So I can’t really tell you why I noticed this buck had nine points. Other than that, he was the exact twin to the 10-point I had shot at in the wind the night before.

My buck was not where we expected to find him. After two hours of looking I was second-guessing myself again and again. I had just let a world-class buck go because of my obligation to a deer that was gone. We figured it out, finally. The buck moved back into the trees, probably to get out of the wind. Sometime during the night the coyotes found his cooling body and feasted well that night.

They were considerate enough to leave the antlers and cape undamaged, but that did little to reduce my rage. None of this should have happened. If I had been better tuned to the fine print, if only I had adjusted my wind hold a few inches more, things would have been different.

I didn’t care about myself, the pain I was feeling was deserved. I was ashamed for what I put this buck through. I know it’s part of hunting and it happens to all of us sooner or later, but none of that mattered. I needed to beat myself up for a while.

In the end we probably went above and beyond in passing on two other opportunities when we thought the buck was alive. I did that only because of my faith in my shooting knowledge and my belief that hunting in the real world is often a wild and unpredictable event and you need to trust yourself. Perhaps my strongest belief here is that you clean up your own messes. We worked very hard to find a buck that many hunters I know would have abandoned in half the time. I beat myself up, even as I bathed in the success. I know that sounds contradictory, but it’s not.

Long ago, I was running out of wall space and money so I set a very high bar for any whitetail I would mount. I have them all—every single one—and many of the best are European mounts on my office wall. I have not had a shoulder mount done in a decade. This buck misses my self-imposed size limit, but Pete Lajoie, one of the best whitetail taxidermists alive, is working on him.

Will it be a tribute to a great buck or penance for me to see him every day on my office wall? Perhaps it’s a little of both. It will also be a constant reminder to always remember the fine print.