If I ever die in an automobile accident, it won’t be because I’m texting or falling asleep or even practicing my goose calling while steering with my knees (a perfectly safe practice, I can assure you). It will happen because I’m gawking at wildlife, probably at flocks of Canadas feeding in some field, and almost assuredly in December or January.

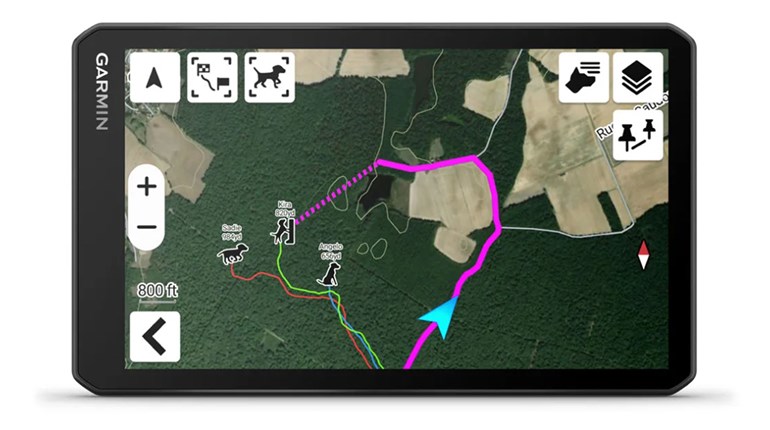

Feeling, as I often do then, somewhat perplexed and often defeated by educated geese turning so many promising hunts into a track record of uneven results, I’m always curious how geese are behaving in fields from one day to the next and under various weather conditions. Bunched up or spread out? Mostly feeding or loafing? How many heads are up; how many are sleeping? How are the flocks distributed, and in what kind of field? Since late-season honkers can be so hard to decoy, I’m eternally on the hunt for any scrap of intelligence that might turn the odds in my favor.

Which, thanks to the industry I’m in, has allowed me to befriend some of the best waterfowlers in the world and glean all sorts of useful information. One of those experts is Fred Zink, world-champion caller and founder of Zink Calls and Avian-X Decoys. Fred’s greatest strength as a hunter is the thousands of hours he’s spent simply observing geese, much of it after the season and for hours at a sitting. That has enabled him to accumulate a treasure trove of knowledge on goose behavior, and his keen eye for detail and power of observation always make me feel like I’ve been sleeping most of my life. I’ll look at geese on the ground and see a rough pattern upon which I can arrange my decoy spread; he’ll notice they’re concentrating on a row of winter wheat where the snow and ice have just melted. Pretty much nothing escapes his notice, and when you hunt with him you’ll find he never sets a spread haphazardly. Every decoy is set down based on what he learned from his most recent scouting session.

Formulating a (Different) Plan

By the time January rolls around, big migrator days may be few and far between, and the geese in your area might have been there for weeks. While they’ve likely been hunted all along their migration route, now they’re pretty cued into what’s happening in the ’hood. They’ve seen pretty much everything local hunters are throwing at them, and they know how to pick out all the warning signs: the rectangular outlines of layout blinds, the familiar decoy patterns, the spreads placed in the same places in every field, the same raucous calling and aggressive flag waving. That’s why if you want consistent success, you’d better pay attention to what’s happening around you.

Smart hunters scout not only the geese but other hunters as well. Now’s the time when you have to be targeted and specific in where and how you set up. First, you’ve got to pay extra attention to mimicking exactly what the geese are doing: what kinds of fields they’re now using, where in those fields and why, and how they’re distributed. In short, you can’t afford not to be ultra-realistic in your presentation, at a time of year when what’s realistic can change from one day to the next. Equally important is offering geese a different look than other hunters. Most hunters are creatures of habit and will use the same spread over and over again. Geese, on the other hand, react constantly to changing weather, temperature, food availability and hunter pressure.

The “X” is Important, but Good Concealment Rules

Once geese have been in an area for weeks, they know where the food is, and by now it’s getting harder to find. Setting up in the middle of a grain field might have worked earlier, especially when new, less-educated geese arrived. But those spots are now played out, and the geese know it. So you’ll have to pay special attention to what and where the birds are concentrating on.

For grain fields late in the year, Fred Zink recommends hunting the edges, because that’s where there’s still an abundance of grain. “To find food geese will continue to broaden their range as winter progresses. While they may have stayed away from field edges earlier on, now you’ll see them up against ditches, weed lines and fences.

“There’s a certain amount of trial and error, but I’ve found that 15 to 20 yards from a field edge usually marks what I call ‘the invisible line of danger,’ where geese decide that being any closer to cover is not worth the risk of feeding. A killer strategy is to place lots of decoys along that invisible line, which will typically follow the contour of the field edge. That will tell approaching flocks that there’s a lot of food there, and that the geese have been there for a while and it’s safe. Remember to spread your decoys along that line, not place them in an unnaturally tight ball.”

Field edges can be a boon to late-season hunters because, now more than ever, educated birds are experts at picking out hunters. As Zink laments, “I never thought I’d say this, but while being on the ‘X’ is important, being well camouflaged is more so. Fact is, over the last five years geese have become so much better at spotting signs of danger. That goes double for late-season birds, so if you can’t find good concealment where the geese are feeding look for the closest cover in line with their approach from the roost.”

Join the Green Party

Most hunters think of cornfields when the temperatures plummet. After all, corn’s carbohydrates will help fuel the geese through the bitter days. And that’s true when it first gets cold. But since corn is low in protein, and can also hold lots of snow that eventually crusts over, by January they’ll be looking for other accessible protein-rich food sources, in particular winter wheat, alfalfa and grass. As Zink puts it, eating steak for a month might sound great, but eventually you’ll crave other foods.

Zink has observed that, often by mid-morning, stems of dark-green winter wheat will have absorbed enough heat to melt the ice immediately around them. He’s watched hungry geese walk up rows of exposed stems, plucking one after another. Fred’s also quick to note where melting or windswept snow exposes food—excellent places for decoying birds, particularly along drifted-in ditches that make great locations for concealing blinds.

The area I hunt most during the late season is full of cattle operations and hence lots of pastures. Some of my best hunts have been in grazed-down grass, where intermittent warm days send fresh green shoots sprouting up. Geese love these pastures and will often loaf in them even after feeding on grain first thing in the morning. They make wonderful mid- to late-morning hunting spots, and the birds are typically less wary coming to them, thanks to most hunters concentrating on grain fields. Don’t pass up these under-hunted hot spots.

Decoy Strategies for Late Season

January weather can go from extreme cold to days in the 50s, and you’ll need to tailor your spread to the conditions. As temperatures plummet, more often than not the geese will fly out late (and the colder the later), and they’ll come out once, unlike morning and evening flights common in more moderate weather. In extreme cold it’s all about conserving energy, and geese might wait until 11 a.m. to fly to a field, only to plop down on their bellies and pass much of the day in that position, feeding on what’s in reach or what happens to be exposed after the snow underneath them has melted off. Zink has watched countless geese feed in this manner.

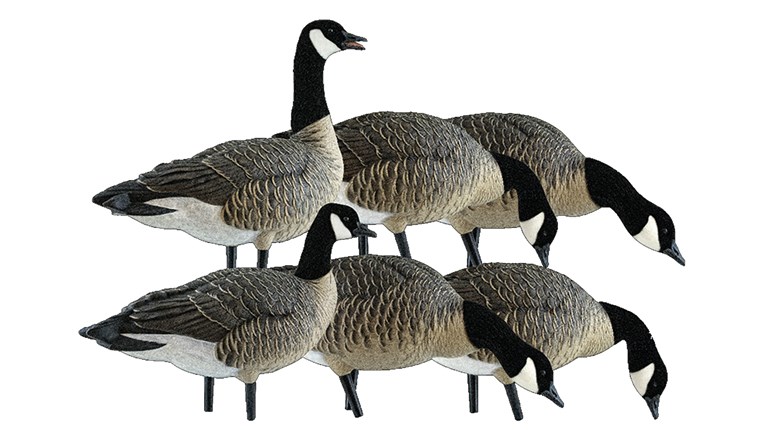

In general, when it’s 10 degrees or below, geese will bunch up tight, so Zink will cram his decoys together, although not in one unnatural-looking wad. If he’s using 60 to 100 decoys, for instance, he might arrange them in six to seven tight bunches with a few walkers in between. And, most important, at least 80 percent of them will be sleeping or lying down. Shell decoys are ideally suited for late-season hunting, as are full-bodies without bases. Zink designed his Avian-X full-bodies with retractable bases precisely for this situation. If you use your standard mid-season spread with plenty of active feeders and walkers, educated geese will know something’s not right.

Warm trends can be a boon to waterfowlers, exposing food previously iced over and often bringing geese that had been forced farther south to come back in large numbers. On these migrator days large spreads are usually most effective, but with the decoys spread out and with plenty of active poses. Remember, you’re trying to imitate geese that are hungry and searching for food in a field that may have been picked over a bit earlier in the year.

For most late-season hunts, any spread that’s different from what other hunters are using can work magic. For instance, I’ve had good luck using silhouettes when the ground’s soft enough for stakes or there’s enough snow to keep them upright. As long as hiding outside the spread isn’t problematic, a super-small spread can also be effective. One of

Fred Zink’s favorite late-season setups, when he can hunt on the “X,” is using four to six decoys with a pair off to the side. I’ve had good luck on smaller flocks hunting over 12 to 18 decoys, placing them in an irregular, scattered formation. Which brings up a good point about late-season spreads: The more irregular you can make them, staying away from discernible and traditional decoy patterns, the less they’ll look like the competition’s and the more convincing they’ll be.

Why Pairs Aren’t any Fun … But Can Be Useful

You’ve probably been frustrated by all those pairs of honkers ignoring your decoys—the same ones that seemed so easy to fool earlier. Fact is, by mid-January Canadas are well into pairing up for the breeding season, and as a rule they want to be by themselves, to the point of running off other geese that dare to get too close. The good news, according to Zink, is the majority of geese, being less than 2 years old, are non-breeders and are still happy to drop into spreads as long as everything looks right.

So how do you incorporate pairs into a spread so it looks more realistic, but still have them work for you? Since younger geese will stay clear of them this time of year, Zink pairs up aggressive male poses with relaxed females outside the area where he wants the geese to land. The pairs essentially keep younger geese from landing to the sides of the main spread and funnel them toward the landing pocket.

When geese are flying high, a few pairs set 60 to 100 yards downwind of your spread can get them to drop altitude out of curiosity. Then they can be called to your spread, low and in easy range on the first approach. This is a wonderful late-season tactic, because if you allow educated birds to start circling your spread from higher up, the outcome is rarely good.

Hunting late-season geese isn’t rocket science, but everything you do has to be deliberate and with attention to every detail. Change your tactics to match the conditions, pay attention to what the geese are doing right now and try to be different than other hunters in your area. You’ll be one giant step closer to consistent success.