Tap tap tap tap tap tap, rattled knuckles on Land Cruiser roof. Their machine gun cadence bespoke urgency, so Dries Bronner, my professional hunter, stood on the brakes, causing a red cloud of Namibian dust to pass us like a fog. Instinctively I grasped for my rifle and scanned the horizon for game—perhaps a kudu or warthog or maybe even a lion or something—but spied nothing. So my eyes followed my PH’s to the pockmarked sand below the tires. I guessed it was another “whitetail”—a gemsbok, but then again, you never know what the African bush may provide.

Frankly, it does little good for a 10-day client like me to look at the ground at all, but dang it, we are curious creatures who don’t like feeling useless, and so we must. Yet despite my study, the two-track looked like little more than a busy public beach with an infinite number of indistinct dimples made by random feet; like a driving range with a thousand divots—you know a golfer made them, but that’s about it. But to Piet, the tracker in the back of the Land Cruiser, each dimple revealed facts that told a story and possibly dictated our next move. Hushed chatter emanated between Dries and Piet in Afrikaans. I waited for the verdict like a dumb dog expecting a treat. I believe it tickles guides to keep their clients in the dark, as least for a few moments.

“Gemsbok. Very fresh,” relayed Dries, finally. His voice was hushed and more urgent than normal, so I translated this to mean, “Big gemsbok bull. Very close.” By now I knew the program, so without speaking or asking questions I eased open the passenger door and slithered onto the hot sand just as he killed the engine.

I’d almost taken for granted that Piet had deduced all this info by glimpsing one track from the back of a Toyota going 20 kilometers per hour through a haze of dust, amid hundreds of other similar tracks before we’d even crossed it. That’s just what these guys do. To a tracker, tracks tell a story that forms a never-ending book written in a language I can’t understand. And because the trackers do it effortlessly, it’s easy to begin taking this incredible skill for granted.

A few days prior, for example, we were at a waterhole at dawn, searching for tracks of a mature eland bull—the largest of the antelope that can weigh nearly a ton—when I saw a track slightly but obviously bigger than the rest. Why Dries and Piet hadn’t seen it I couldn’t say. Dries must have noticed me staring at it.

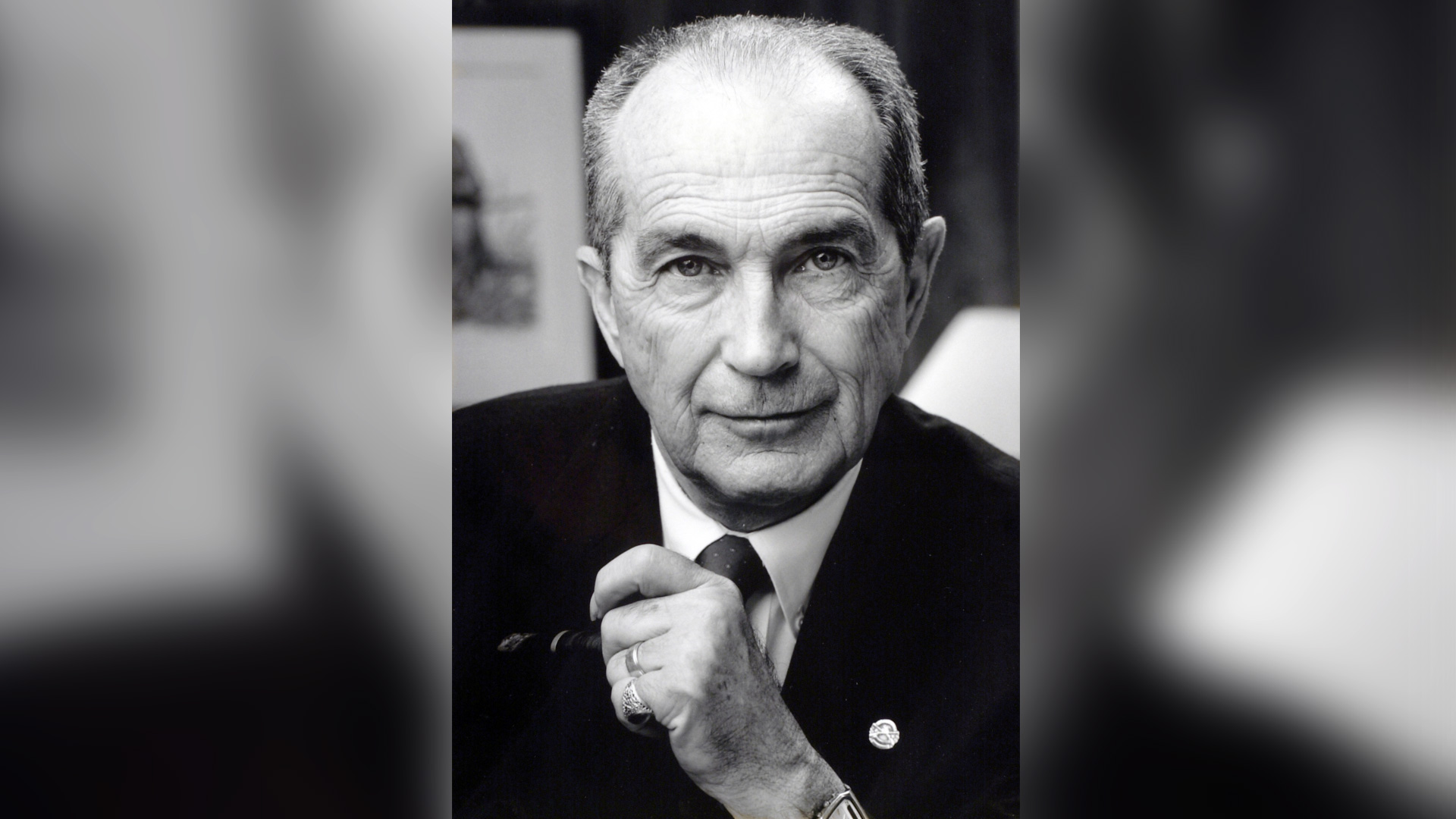

“Giraffe,” deadpanned Dries. “They’re up ahead about 2 kilometers,” he said, nodding to the north as he looked at me and winked, all at the same time. Dries is about 5-foot-8, built like Kirby Puckett and always has a glint of mischief in his eye. He’s a stand-up joke teller, camp manager and lead guide for safari outfitter Jamy Trout. Don’t try to out-walk him.

Giraffe. Of course. I’d forgotten about those. Idiot. And then Dries pointed to one nondescript print in the loose red sand among thousands. It had no edges nor defining features. It was just another shallow pockmark on a beach. “This is our boy,” he said, meaning the eland bull.

We spent the next five hours tracking (I use “we” generously) this particular eland even as he joined with several other bulls and crossed thousands of other tracks—fresh and new, some probably his own from days and weeks before. I should have bagged the bull about 10 kilometers later—had I not missed him at 200 yards—but that’s another story entirely and one I’d like to forget. The point is, it surprised me none when the tapping on the metal roof of the Toyota now urged Dries to slam on the brakes and to know without a doubt there was a good gemsbok bull nearby, sight unseen. The tricky part, however, is defining “good.”

The Whitetails of the Kalahari

I’ve noticed hunters, or rather people in general, tend to compare foreign things to those they know. If you’re a Texan and it’s your first safari, it’s mandatory that at some point you look at the jess and brilliantly observe, “This looks just like Texas!” And I’m no different. To me, gemsbok are the whitetails of Namibia. After all, they’re nearly as numerous as whitetails are in South Texas. But the analogy goes deeper than this, as Dries, having hunted deer in Georgia once, explained.

It’s not that the two species have much in common physically; rather they are both iconic game with rich hunting traditions in their respective countries. Like most rural Namibians, Dries grew up hunting gemsbok like we do deer. He cut his teeth on them, hunted them for meat and pleasure, and raised his son Rheinart the same way. He can judge an inch of horn just by glimpsing one from across a mirage-soaked veldt. As a former government culling officer and currently a PH guiding clients, he’s certainly seen thousands of these animals hit the turf. Still, he says hunting them never gets old. When he spoke of them as whitetails, I got it.

The most numerous antelope of the Kalahari Desert, these 350-pound, swishy-tailed ungulates are prolific, adaptive, hardy, tasty and challenging due to their speed, stamina and olfactory senses. Their eyesight is no less than incredible. Gemsbok can survive in temperatures that would turn horse hooves into Elmer’s glue. They can go for days on no water, often at a slow trot. They can also take a lot of lead. With clown-faced hides, head-turning horns and backstraps coveted on BBQs everywhere, they are one of the world’s perfect game species.

Trophy quality is measured in inches of their long, antennae-like spikes for horns, veritable weapons that have been found broken off in very dead and regretful lions. Mature cows can have longer horns, but the bulls’ are thicker. And nearly all of them are almost identical with the only variance being length and diameter. The difference in a trophy bull and an average bull is a matter of a couple of inches, say 34 inches for a trophy and 36 inches and over for an exceptional animal—like a Boone and Crockett-caliber buck. I’ve never been that much of a tape-measure guy, but then again, I don’t like shooting young animals. I guess that’s the QDMA in me.

In Namibia, much like trophy deer hunting in the States, the object (when not hunting for camp meat) is not to kill just any animal, but to take a “good one” so that doing so is made memorable by the challenge of it. I mean, how much fun would deer hunting be if each year you went out and shot the very first deer you saw? I’m not knocking meat hunters, but personally, I sit long hours in a treestand—or in this case a hot desert—to savor the hunt as much as I can. And while some hunters prefer horn length to fulfill their challenge, I’m a mass guy. Or better yet, I like an old, on-his-way-down male that’s soon to be hyena kibble. If his horns are great, that’s a bonus. And if he’s a retired old boy with massive, non-typical horns, well, then, stop the truck immediately, sir, and let’s rack a round!

Weird but Wonderful

Almost as soon as my boots hit the sand of the two-track, I saw the last few animals of what was likely a small herd of gemsbok filtering through the camel thorn trees. They were merely 60 yards away, unaware of us due to the wind in our favor, and hastily moving to our right. One was clearly larger than the rest. I thought I saw something interesting about it, but without getting the Nikon up in time, I couldn’t be sure … .

We followed the track of the herd for only a few minutes before it collectively stopped to rest. Dries took a knee, glassed again then leaned in to whisper. I could sense some disappointment in his voice.

“Old bull, but horns that go like this,” he whispered, slashing his hand over his head, rather than straight up and out like a TV antenna. “Thought I saw it from the truck, but now I’m sure.” He was disappointed because after nearly a week of hunting these Namibian whitetails with failed stalks and no success, it meant we’d drive back to camp once more empty-handed, something that’s not too common for an African plains game safari.

You see, unlike non-typical whitetails, weird horns in gemsbok are rare and usually caused by injury. For whatever reason, most hunters tend to pass them, instead opting for a more classically styled, perhaps representative, trophy. But I might be a little weird, too.

“I want him,” I said. And suddenly my PH’s eyes regained their gleam, as if his team had just recovered the onside kick and suddenly had one final chance to win.

Using the cover of the thorn trees while minding the many eyes of the herd, we stalked the old bull just as hunters have done for eons. At some point in the closing moments, it’s up to the hunter to find a favorable shooting position and take the shot if and when he knows he can. So without words, I crawled ahead of Dries and nestled the Kimber on the shooting sticks. I found the bull in the scope, took a good, magnified look at those unmistakable horns for verification then centered the crosshairs on the bull’s shoulder. But before the trigger broke, the bull stood and walked forward. Sensing danger, he looked at us and stopped. Seconds dripped by as he nervously tested the air, looking for any reason to swish his tail and wheel. With fleeting light threatening to close the book on this story forever, I maneuvered right a few inches and found a tiny window through the brush.

The report see-sawed me off the sticks and sent the herd flying. Except one. The old bruiser lay dying, heart shot, kicking reflexively at air.

Anti-hunters will never get it, but there are few things more satisfying yet bittersweet than walking up to hard-earned game after a perfect shot. A record-book bull he was not, not that I cared. Like some of the non-typical whitetails on my wall, perhaps only his mother thought him beautiful. I thought him perfect. The bush had provided indeed, and I was grateful.

I grasped his horns and patted his shoulder, still warm but losing heat swiftly like the shadow-laden sand beneath him. Dries stood back and admired the scene while exchanging some words in Afrikaans. I was curious, but I knew better than to ask. Finally, he spoke.

“Piet says this old fighter had only two more weeks to live before falling over dead of old age,” said my PH.

I cocked my head incredulously. “How in the heck does he know that?” I asked.

Dries just winked.