“The delight of wild scenery, the exhilaration of bodily exercise in pure air, and the ever-varying circumstances of wild and majestic country; the inspiring sense of solitude, broken only by the whistle of the marmot or the laugh of the loon; the intimate communing with Nature in every aspect of sunshine, mist, and storm—all these, and with them the satisfying of that hunter’s instinct which is one of the most deeply rooted things in human nature; the delight of pitting the intellect and the senses against the instincts of self-preservation of a really wild animal—that is wilderness hunting.”

—Townsend Whelen, Wilderness Hunting and Wildcraft, 1927

The spring runoff had pushed Horse Creek to its limits, and the roar of the watercourse through the narrow, rocky canyon was nearly deafening. I tensed in the saddle as my horse negotiated a tight trail. The terrain was so steep that, leaning toward the uphill side, I could reach out and almost touch ground. If I fell off my four-legged friend, gravity would carry me to an icy, cold swim—or death.

Trusting my horse, I craned my neck and looked through the treetops. I was scanning for a bear in the slivers of neon-green grass growing between jagged Precambrian rock outcroppings on the nearly vertical mountainsides. I wondered to myself how we’d get up to any bear I might see and shoot, and more importantly, how we’d get it down.

We were 10 miles from civilization, in the heart of the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness. I was riding a horse, carrying a rifle and breathing possibly the cleanest air my lungs had ever consumed. I was coursing the watershed of the Salmon River, described by Lewis and Clark as “foaming and roaring through rocks in every direction, so as to render the passage of anything impossible.” The river got its “No Return” name because although in the early days boats could navigate down it, they could not return upstream through the fast water and numerous rapids.

The Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness is a seemingly endless stretch of hellacious mountains, deep canyons and wild whitewater rivers that encompasses 2,366,757 acres in central Idaho. With the exception of Alaska it is the largest contiguous federally managed wilderness in the United States. It is more than unspoiled wilderness; it’s a national treasure.

Senator Frank Church sponsored the Wilderness Act of 1964, which protected 9 million acres of land as part of the National Wilderness Preservation System. He also introduced the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in 1968, which included the Middle Fork of the Salmon River. The 1980 passage of Church’s Central Idaho Wilderness Act created the River of No Return Wilderness by combining the Idaho Primitive Area, the Salmon River Breaks Primitive Area and a portion of the Magruder Corridor. In January 1984, Congress honored Church by adding his name to the River of No Return Wilderness.

Riding through this expanse of pristine nature I felt like I was in 1800s America, at the center of everything wild. I felt like the Salmon River’s own Buckskin Bill, who once said, “Oh, I’m patriotic. Ever’ time a bald eagle flies by I take off my hat.” In fact I had seen an eagle that day, and I had taken off my hat.

Mesmerized by evergreens three telephone poles tall and a canyon so steep it seemed to defy the laws of geometry and nature, I was not paying enough attention to my mount or purpose. I heard my guide, Adam Beaupré, whoa his horse, and I immediately reined up to see him pointing skyward. Even at what seemed like a quarter-mile away, the bear stood out like a wart on a witch’s nose. Its black coat was dark in contrast to the fresh and brilliant green grass, and the sun lit its back like it was covered in aluminum foil.

“There’s your bear,” said Adam, and the roar of Horse Creek seemed to fade away with the thump of blood now swiftly pulsing through me. We hurriedly dismounted, Adam secured our horses and I pulled my rifle from the scabbard. Instantly I realized my bipod would be of no assistance when shooting at an angle steep enough to paralyze a protractor. After some panicked searching we settled by a fallen tree with a trunk about 3 feet in diameter. I struggled to get into some semblance of a shooting position unlike anything I’d learned in the military or at Gunsite Academy. All the time the primary axiom of rifle shooting was echoing in my head: If you can get closer, get closer; if you can get steadier, get steadier.

Closer was not an option. The bear was nearly 400 yards straight up a canyon wall so rugged and perilous it would have strained the version of me that was 30 years younger and had just graduated basic training. Steadier it had to be. I managed to slide my legs partially under the fallen tree and rested my rifle vertically on the log. I guessed the angle to be nearly 30 degrees. Adam slid in behind me as I found the bear in the scope. He called the range at 365 yards, and I applied the correct holdover with the Ballistic Plex reticle in the Burris scope.

“You ready?” I asked.

“Yep,” Adam whispered, and my finger broke the trigger at almost exactly the same time his lips closed together.

The bruin reacted with a jerk and jogged about 20 yards to the cover of a burned-out section of young trees about the size of a mobile home. Adam called the shot a miss and jumped up from his spot over my shoulder.

“Let’s move fast,” he said. “Get a better angle and a better rest.” I crawled out from under the log, and we sprinted up our side of the canyon 100 yards or more. I no longer noticed the sound of Horse Creek.

We managed to find an opening through the tops of the trees where we could see the bear milling around in the tangle. It seemed fine. I continued to watch the animal as Adam tried to construct a shooting platform, one that would allow me to shoot uphill while positioned on a downhill slope. He worked with rocks and logs for a few moments, but I still could not rest the rifle with the elevation needed to shoot the bear.

Positioned behind a huge Ponderosa pine with my rifle trained on the bruin, I realized I had a big knife clipped in my pocket. I pulled out the Southern Grind Bad Monkey, opened it up and instructed Adam to drive it into the tree trunk with a rock at a precise location. The result was a sturdy makeshift “limb” I could use for a rest. I looped up in my sling and was rock-steady on the bear. Then we waited, trying to calm our heart rates while hoping the animal stepped out in the clear.

The bear was in no hurry. Unusually, it was preoccupied with licking its paw. A bit perplexed by the results of my shot, I asked Adam if he’d given me the horizontal range or the line-of-sight distance to the target; his rangefinding binocular was capable of providing either reading. This was critical because when shooting at this kind of distance, and at these kinds of angles, it mattered—not just a little, a lot.

Like a good guide should, Adam had his unit set to horizontal range, the range used to calculate bullet drop. However, when he’d told me the range was 365 yards, I mistakenly assumed he’d given me the actual, line-of-sight distance. To convert to horizontal range I had then reduced his reading by 20 percent, which is about right for a 30-degree angle, and held dead-on with the 300-yard tick mark of the Ballistic Plex reticle. This had resulted in a drastic variance from my intended point of impact. My first shot had impacted about 10 inches lower than where I was aiming. This explained the bear’s unusual fixation with licking its paw—it had a bullet hole through it!

We squared this away on the side of the canyon and confirmed the new, horizontal range to the bear using both our rangefinders. From our new position the bear stood, as far as bullet trajectory was concerned, 403 yards away. Lesson learned: When your guide is running the rangefinder in steep country, have this conversation well before the shooting starts!

When the bear finally stepped into the open I placed the third tick mark—the 400-yard mark—right on its shoulder and squeezed the trigger. The bear was hit but broke into a run and passed behind another Ponderosa treetop that was between us. I grabbed my rifle and scooted to the right, picking up the shooting sticks as I ran. Planting my bottom on the steep hillside, I once more looped up in the sling, tracked through the bear as it ran, and when the reticle’s 400-yard mark passed its nose I broke the trigger. The bruin collapsed and began to roll.

And roll it did. It rolled … and rolled … and rolled some more. Somersaulting over jagged rock outcroppings, tumbling through bright green patches of grass, bouncing off standing and fallen tree trunks, the dead bear provided a spectacle unrivaled by any of the gunfighter falls in old B-movie Westerns. After plunging almost 400 yards the bear came to a rest just a matter of feet from the torrent of water at the bottom of the gorge. Congratulating ourselves and wondering what kept the bear from rolling into the rushing water, we then began discussing the apparently impossible task of getting to the animal.

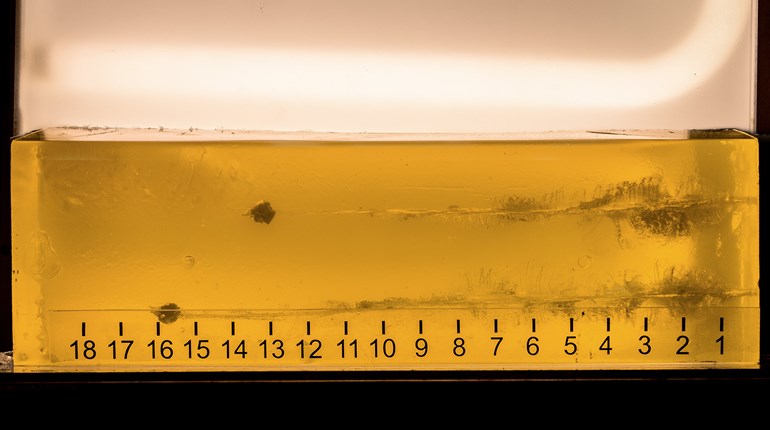

The recovery would be the hard part. Horse Creek was a raging, rock-filled, whitewater blast of ice-cold melted snow. Few would have braved it in a raft and even fewer would have attempted the rush in a kayak. We mounted up and rode back to camp to get supplies. We’d found a huge log across the creek, and the plan was for Adam to scoot across the log, travel up the other bank, secure the bear and then float it across the river at a small oxbow with a rope attached. The plan worked to perfection. The bear was the only one of us who got wet.

We learned the bright reflection off my bear’s back—an aspect that immediately stood out when we first spotted the bruin on the slope—was due in part to the silver-colored hair running down its spine. Later the taxidermist said it was only the second bear he had seen with hair like that and both had come from Horse Creek. (When I told him the story of the hunt, he also said it was the only bear he’d ever seen that had been, kind of, killed with a knife.)

As a young boy hunting whitetails in the Allegheny Mountains of West Virginia, like many Easterners I had dreamed of packing into the wilds of the West on a big-game hunt. Some dreams subside with time; others prowl your soul even though they seem as unobtainable as the fountain of youth. At the half-century mark I had managed to drag a dream from a coalmine-like hole of my memory and make it come true. I had saddled a horse and rode into the Salmon River wilderness with a rifle. I went home feeling a bit rejuvenated, but the sights, sounds and stillness of the wild still haunt my insides. In the River of No Return Wilderness I felt so very inconsequential, but I was also reminded we’re genetically programmed to exist with nature in its true form.

Into the Wilderness with HCO

When most folks think of trekking into the backcountry on a big-game hunt, they think of elk or sheep. As majestic as these species can be, they come with a price tag just as stunning. Hunting in the United States is not a sport for royalty like it was for our European ancestors, but outfitted backcountry hunts for these iconic animals are mostly for the wealthy for sure. Thanks to Adam Beaupré of Horse Creek Outfitters, wilderness dreamers have another option.

Horse Creek Outfitters (HCO) is based in Challis, Idaho, and operates on roughly 300 square miles of public land. A respected outfitter in Idaho for more than 20 years, HCO offers guided opportunities for elk, deer, moose, pronghorn antelope, bighorn sheep, mountain goat, lion, coyote, wolf and bear. HCO operates in what seems like a never-ending expanse of wilderness, with camps as high as 9,000 feet and as distant as 10 miles into the backcountry, far beyond the reaches of motorized access.

Like many backcountry elk hunts, HCO’s offerings push the 10-grand price tag. However, the outfitter’s steal of a deal is its backcountry black bear/wolf combination hunt in the Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness. You can saddle up with HCO and ride for miles into this majestic, unspoiled, wilderness wonderland to hunt black bears for five days for $3,250. A wolf tag is an extra $500. I’d suggest you buy one. Even though we saw no wolves during our hunt, the next group of hunters took one home.

You’ll climb up and look over country that will cause your jaw to drop. You’ll develop a new respect for horses and mules. You’ll eat some of the best pancakes ever put on a plate. You’ll also go home feeling a little bit closer to the mountain men who tried to tame this land and the Nez Perce people who roamed there.

You’ll need a water bottle, sleeping bag and pillow. HCO provides everything else. If you get a bear or wolf, you can drop them off with River of No Return Taxidermy in Salmon, Idaho. Daniel Stephenson does excellent work.