The trackers at Mutemba Safaris’ camp in Mozambique were cracking up as our group checked the zeroes on our buffalo rifles. Normally pretty aloof around clients, they were clearly amused this time. Thankfully our shooting wasn’t all that laughable—it was the smoke, or as I learned later, in the words of lead tracker Daniel Chiuimbu, the “big smoke” belching out the muzzles with each shot.

Blackpowder hunting for Cape buffalo certainly isn’t unprecedented, but rare enough that few folks now working in the safari trade ever encounter it. Aside from a few diehards, who really wants to march up to a hell-on-wheels 1,500-pounder armed with a front-loading single-shot?

Well, Dudley McGarity for one. For 20 years Dudley has worked as hard as anyone to spread the gospel of muzzleloader hunting. In his own words, he’s been a “disruptive marketer” whose company, CVA, slowly but surely took control in the category with products like the Accura rifle and PowerBelt bullets. Ever since a failed safari in 2003, Dudley coveted this particular belt notch to cap his run in the muzzleloader business, but there’s more to it than that. Here’s a guy who was a miler on Georgia Tech’s varsity track team, a guy who solos in the Montana wilderness, chasing elk with a recurve bow. Not a guy who backs down.

Michael McMichael, creator of the PowerBelt line, is another dedicated muzzleloader and one quite experienced in taking on the biggest game in Africa and North America. He wanted in, too. Somehow I got grandfathered into the trip, perhaps because Dudley and I chanced to meet up at the Atlanta airport in the wake of that long-ago bust safari. Over the years we speculated about a rematch, and though I would have been perfectly happy to tag along with a cartridge rifle, the whole thing was too intriguing to miss. Another business associate, Dan LaFond, was joining in as well for his first Africa safari.

We booked our adventure with Wayne Wagner, a hunting entrepreneur who lives and operates in South Africa, but who also has devoted nine years to carving a haven out of the bush in wild Mozambique. More than two decades after a crippling civil war, the country has become one of the gems of African hunting. The Mutemba concession where Wayne is a partner sits just across the border from South Africa’s famed Kruger Park and Gonarezhou National Park in Zimbabwe. It hosts guests to a luxury tent-camp experience right out of the 1930s, and the hunting may be even better than back in those golden days.

■ ■ ■

Early mornings we searched for promising tracks among the disc-shaped hoofprints, ranging from softball to pie-tin sizes, which pocked the concession’s dusty roads. Any that were relatively fresh merited a closer look, whereupon Wayne and his trackers jumped out of the Toyota to judge the size of the herd, the presence of big bulls, and where the herd was heading (generally to or from water). Mostly the sign was not encouraging and we drove on, searching the winding two-tracks between waterholes. In the early-morning chill we found and left two herd crossings; one coming from water and heading for the property line, a second moving into dwarf mopane where it would be tough to sort out an old bull until they bedded later. Time to move on.

Around a turn Wayne abruptly hit the brakes. Lounging on an ant heap 40 yards off the track were two males glaring back at us, but not with the repo-man look we hoped to encounter. They were cheetahs, grasslands sprinters seemingly out of place in the miombo forest. Grudgingly, casting a “catch us if you can” taunt, the leggy, spotted cats tramped off.

Like all good safari areas, Mutemba’s concession holds plenty of wildlife and watching for it is an essential part of being there. Along with herds of buffalo, we viewed all manner of antelope from hulking eland to tiny suni, including some of Africa’s most magnificent kudu and nyala. There were other cat species, lions and civet, hyena, baboons, monkeys, mongoose, birds so colorful they resembled flying jewels, and at one waterhole I witnessed a pair of Egyptian geese harassing a hapless monitor lizard. It wasn’t all watching either, as our entire group of eight sampled the plains game, and we’ll report on what happened in a future issue. Chiefly though, we fixated on the buffalo.

Four Encounters

On our first hunting day, Michael McMichael and PH Ian Brown found themselves in a tense three-way drama. It was late afternoon when they spotted a great buffalo, which abruptly spun around and loped off, aggressively tossing its heavy yoke of horn. Something dodged to the side—a lioness, either bumped off its pads or ducking out of harm’s way.

As the bull ran atop a knob, Mike and Ian saw there were actually three lionesses present, one of which didn’t run far. The big female eyed the human intruders from inside 100 yards even as the buffalo stood watch from higher ground.

With the sun dropping, Mike and Ian focused on stalking the bull, which meant proceeding on all fours. But they weren’t the only ones creeping forward; so was the lioness, stealthily advancing in their direction. When the men halted, she did too; when they resumed she inched closer. When at last their stalk drew within shooting range of the buffalo, the lioness was just 40 yards away. As they stood to shoot, she froze into a crouch. While his client drew a bead on their quarry, Ian readied his .500 Jeffrey stopping rifle in case the lion charged.

Michael’s shot broke the spell; the muzzle flash, the BOOM and a blast of smoke finally sent the predator on its way. Meanwhile the buffalo also ran off.

What followed then was a tracking marathon that extended another day and a half. No blood was ever found, and when they jumped the bull again, it lit out at full speed, denying a second chance. It had been a clean miss—good news, nonetheless galling and puzzling. Among our group Michael was the most accomplished blackpowder hunter, the only one of us who had previously killed dangerous game with a muzzleloader, and not just Cape buff, but elephant and big bears, too. It was hard to fathom the miss, hardest for him, no doubt, but it has happened to me too. Hunting will keep you humble, and that’s not all bad.

Dan LaFond returned with an even better tale, one with so many plot twists it took all evening to tell it. His chance culminated in a shot that sent the bull and its mates off at a gallop. The shot had drawn blood; the die was cast.

Multiple times through the long, hot afternoon the hunting party closed on the herd and relocated its wounded member. More shots were fired, both from our friend’s muzzleloader and the PH’s .375 H&H. The brute refused to go down, creating the kind of hot-pursuit scenario that inspires hair-raising stories. Cognizant of the danger, watching their backtrail, our boys followed gamely right up to sundown, whereupon they found themselves miles from the truck.

After radioing camp for a ride, they sat tight in the dark. Well, sat tight until they heard an ominous crashing through the thick brush, something big closing fast. That set off a scramble, men sprawling in the dirt and climbing small trees, and another shot fired. Whatever stormed through the night passed just yards away and kept going. Only a few stiff sundowners back at the campfire made it possible to recount the close call.

The next morning, starting at the spot of the after-sundown melee, the PHs read the tracks: A buffalo had indeed run past. Was it the wounded bull making a wayward charge? Since Wayne and his trackers were joining the pursuit, I tagged along, and the entire pack of us backtracked in search of sign of the herd. That didn’t take long, but then I was puzzled as the backtracking continued. The reason became clear when one fellow signaled a lone, blood-specked track peeling off on its own. Dan’s bull.

A tense hour along, there was an empty bed stained by a puddle of nearly dried blood. The bull’s time was leaking away, but slowly. For another anxious hour we continued, finding more blood, watching in all directions, speaking very little. A couple of the trackers started lagging behind, but then one of their fellows cupped an ear and pointed out the bull, still upright beyond a fallen tree.

Dan, plus the two PHs, stepped forward and fired almost in unison, and finally it was done. It was both the worst and the best of buffalo hunting, a lesson in grit and strength seen through an overload of adrenaline.

Back at the skinning shed we saw evidence of a high shot that nicked the lungs, and likewise a low, grazing lung hit. There had been a few ineffectual hits, and then there were twin heart shots, likely those at the end that leveled the old warrior.

Dudley hunted harder than any of us. Ten days into an 11-day hunt, after countless sun-baked miles spanning cotton-mouthed close encounters, near-miss setups, and herd after herd spooking into dust storms of their own making, the determined muzzleloader fiend collected his hard-earned due.

Day 10’s herd had bedded around a water pan during the night, but was absent when the hunters checked it first thing in the morning. The fresh—very fresh!—sign meant the 60-plus head couldn’t have been gone long, and so with time running short, the chase was on. Because of a tailing wind, PH Roelof Niemann decided they needed to flank the herd rather than follow right on its tracks. Looping in from the side they spotted two shooter bulls, but couldn’t sort a shot out of the tangle.

Gambling that the herd wouldn’t change direction, the hunters hustled to gain ground and get set up in a spot where the underbrush thinned. Dudley was ready as a parade of buffalo pushed through an opening, at last including a big bull that provided an exposed broadside.

At 95 yards it was a long dangerous-game shot whether you’re firing a muzzleloader or a cartridge rifle. The bullet strike was audible and made the bull buck before he vanished into the smoke- and dust-choked scene. Most of the herd stayed put, milling about nervously. All indications suggested the bull was hit hard, so the hunters waited right there, listening for a bellow to mark the big fellow’s demise.

When the bellow didn’t come, Dudley and Roelof moved on, but not far before they found the bull. It was up and facing them, but with its head hanging. One more shot into the spine at the shoulders dropped the bull and Dudley’s long-delayed quest was fulfilled.

My tale is curious, to say the least. In the annals of Cape buffalo hunting it can’t be unique, but if this is how it normally went, a great and honored sporting tradition might never have gotten off the ground. From the initial spot, through the stalk, set-up, shot and recovery, no more than 40 minutes transpired. From the truck as we headed in for lunch, Wayne saw the bull bedded. It was a loner, a specimen so old it’s face was mostly white. After parking behind some bushes, we slow-crawled on our bellies through a gauntlet of sparse timber, the only brush present to screen our approach. We scooted in behind a knot of four or five trees no thicker than a man’s arm and hatched a plan. Wayne rose ever so gradually and set up his shooting sticks. I followed, rested the CVA on the sticks and inserted a primer. With a gang of oxpeckers dancing across its back, the bull chewed its cud and didn’t know hunters were lurking just 43 yards away.

“See the two birds on its shoulder?” whispered Wayne. I nodded. “Halfway between, follow down, see the green leaf in the dead grass?” I nodded again. “Hit the green leaf,” said Wayne, “and I promise you, you’ll kill this buffalo.”

It hadn’t occurred to me we’d shoot him lying down. Peering through my scope I could see the green leaf perfectly, about the size of a golf ball. I looked back at Wayne and he shrugged. “We can wait for him to get up or make him get up, but … he’s going to be running.”

Again I fixed on the green leaf, my reticle’s red dot steady. One way or another Wayne was going to earn his pay today.

I fired, and the buffalo slumped slightly to the off side. Wayne said, “Here take my rifle for backup,” then changed his mind. “No, no, reload, reload.” I did so, pouring in the powder, tamping the PowerBelt home, trembling a bit as I capped the breechplug, trying to keep one eye on the bull, which had rolled back upright and was rotating its head a little. After my second shot the old-timer settled and didn’t move again. Before the trackers were able to walk over from the truck, we heard the death bellow for which these big animals are famous. It was the only thing about my hunt that followed the script.

Parting Thoughts

Four hunts, four distinct outcomes. What can we learn from such a small sampling?

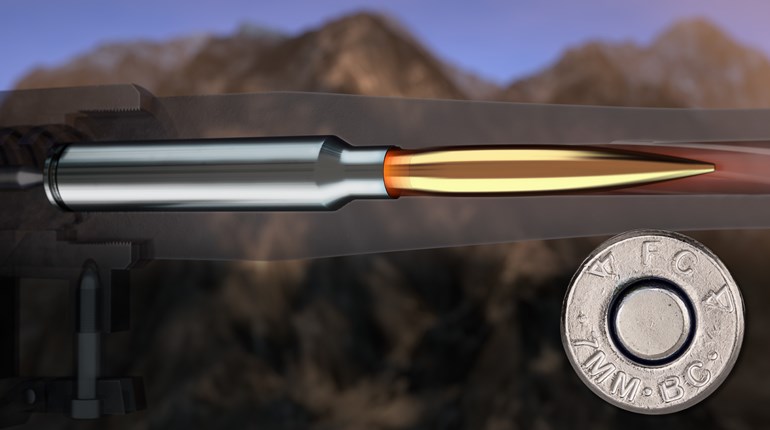

I’d conclude the muzzleloader’s suitability speaks for itself, though how that can be the case isn’t so easy to explain. Our loads generated some 2,690 ft.-lbs. of muzzle energy, about the same as a .270 Win., and far less than the .375 H&H (4,250 ft.-lbs.), generally considered the bare-minimum caliber for buffalo hunting. While various formulae focusing on momentum or kinetic energy have been devised for comparing knockdown power, campfire ballisticians easily shoot holes in all of them. Even so, 150 years’ worth of anecdotal evidence has shown that heavy, large-diameter bullets hitting at moderate speeds can penetrate through vital organs and reliably kill the biggest, toughest animals. There are other theories as well behind the big mass/low energy conundrum. One holds that a bounce effect occurs when a high-speed projectile strikes the heavy, elastic hide of buffalo and bigger game, and another says that very rapid penetration and expansion are countered by increasing drag. Yet another contends that a fast-penetrating bullet can “outrun” the hydrostatic wound cavity forming ahead of it, thus causing it to plow through compressed tissue rather than through a relatively open channel.

Another question I faced, before and afterward, was about the “pucker factor” involved in hunting buffalo with a single-shot. That concerned me plenty in preparing for the safari, and though I drilled on reloading quickly, it was clear I’d never be fast enough to beat an incoming bull. The only real solution, I knew, was to make the first shot count.

And as soon as we actually got underway, it was just buffalo hunting as I’ve known it before. Amid the thrills of close encounters, my attention fixed on being in position and being ready to shoot. It was engrossing as ever, but I can’t say it felt any different this time.

And perhaps one more revelation shed some light on what just happened. As Wayne and I leveled off after our success, his lead tracker, Daniel, knelt beside our fallen bull and began pushing with both hands on its rotund belly. He hadn’t had to track the monster one step, but now grunted with effort and quipped over his shoulder to Wayne. Of course we would set the buffalo upright for photos, but this wasn’t going to do it. Daniel muscled into one big final shove then collapsed laughing. “He says the buffalo swallowed the big smoke,” Wayne translated. “And now he’s trying to make the smoke come back out of its nose. He says it’s too bad the buffalo didn’t know smoking is unhealthy.”