Once in a while, a long career in the shooting and hunting industry helps me see things coming. But that vision is not always clear.

When we were designing our namesake rifle in 2018 we never really considered a long barrel regardless what caliber we might have chosen. Even then, short barrels were hot—specifically, short, stout, threaded barrels. I remember saying, “That’s the trend. Suppressor use is driving it. Suppressor use will only grow. If I’m a hunter using a suppressor, I don’t want a 24- or 26-inch barrel. I don’t want to carry around a tree limb. It’s not a ‘short-barreled rifle’ until the barrel shrinks to less than 16 inches. Watch the market go there.” Thus the Remington Model 700 American Hunter rifle wore a 20-inch, medium-contour, fluted barrel with a threaded muzzle.

Don’t call me Nostradamus. One has only to look at trends in rifle and cartridge design the past 40 years to see how we got here. In fact by 2025 standards our 2020 Rifle of the Year looks old-fashioned—but that’s another story.

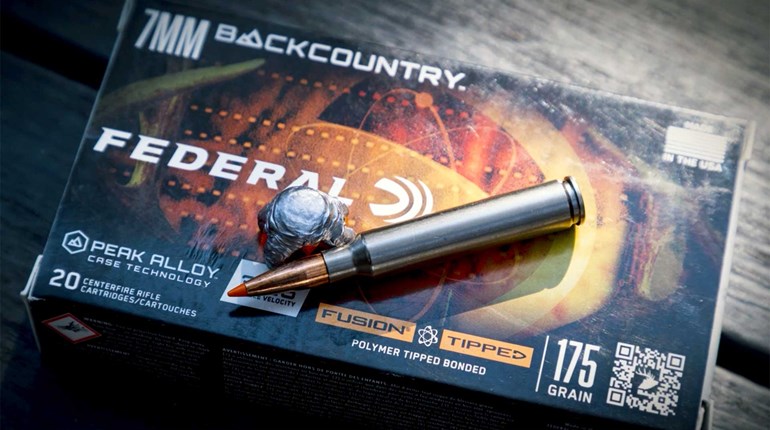

Today’s story is the release by Federal of the 7mm Backcountry, a 21st-century centerfire cartridge designed for big-game hunting that delivers the news from a 20-inch barrel with as much authority as any similar magnum cartridge that launches its bullets from a 24- or 26-inch barrel. It does the job with less runway, so to speak. To do this Federal ramps up pressure—greatly—so the bullet exits the barrel with muzzle velocity similar to any other 7mm magnum. To contain the pressure, Federal uses not brass but a new steel-alloy case.

All of this was on my mind as I digested an invitation last year from Federal Director of Centerfire Products Mike Holm to hunt New Mexico elk with the then-secret cartridge. I knew even before I flew to Albuquerque that I wasn’t the only one hunting with the 7 BC last fall. Big game fell to it across America, and I have yet to hear a poor report. This one is mine, and neither is it a poor report.

Federal just went there–the company just went straight to the end of the trail, really.

The 7mm Backcountry is a long-action cartridge designed by Federal to take big game the size of moose and elk at any practical range from a rifle with a short barrel. Now, before you assume the cartridge works best with a suppressor think again; the 7 BC ballistics touted by Federal were obtained without a suppressor.

Federal merely recognized that many shooters and hunters across America are embracing suppressor use, so it designed a cartridge to produce from a short barrel. But of course shooting this with a can is enhanced because you begin with a 20-inch barrel, and from there you’re hunting with perhaps a 26-inch barrel—better than a 32-inch barrel.

Its ballistics center around a muzzle velocity of roughly 3000 fps pushing trendy, heavy-for-caliber bullets of the 7mm kind, exactly the diameter America has finally admitted it loves. This is significant because for decades there really were only two bullet weights for a 7mm hunter: 140- and 160-grain. Nowadays many are heavier, and Federal’s design allows us to shoot them in more compact rifles. For all practical purposes, this is a non-belted 7mm magnum hunting cartridge that would have been chambered, not long ago, in a rifle with a 26-inch barrel. Actually, before Federal settled on marketing literature that includes “20-inch barrel” I was hearing “18-inch barrel” and that’s what my specially built Gunwerks rifle wore. Frankly, there’s little reason one can’t use a 16-inch barrel (and I hear some gunmakers are doing just that). Worst is you’ll lose some velocity, same as you would with any other cartridge.

The 7 BC is not a trendy, fat-bodied case. It looks at first blush like a member of the .30-06 family, like a .280 Remington, really, especially considering the latter was necked down from the 06 in 1957 to accept a 7mm bullet. Case head diameter is .472 inch, a tick larger than the 06, indicating this is not a magnum and thus fits standard bolt faces. Also, this means magazine capacity may be increased over other magnum-like cartridges in its class. Case length is 2.41 inches, a tad shorter than the .280. Maximum cartridge overall length is 3.34 inches, same as the 06, however, the 7 BC’s neck is shorter.

The 7 BC is approved by the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) with a maximum average pressure of 80,000 PSI. You read that right. This is 15,000 PSI higher than most anything ever SAAMI-approved before. Whew. How? Why? Now the new steel case comes to the fore.

The case is actually a patented steel alloy Federal discovered in use in other industrial categories. It has never been used in ammunition before but it does the job with aplomb. It’s called Peak Alloy (a trademarked name), and as a cartridge case in the chamber it absolves the rifle of containing all that pressure without cracking or stretching.

Unlike other steel cases it is ductile enough to seal the chamber to prevent gas from escaping into the action. It is nothing like Eastern Bloc steel-case ammo, which is hard to cycle, brittle and hardly rust-resistant. This is nickel plated. It is unlike the case of the SIG .277 Fury, which also operates at 80,000 PSI. Whereas the Fury case is three pieces—a steel head, an aluminum washer and a brass body—the 7 BC case is one piece of steel.

Federal found Peak Alloy while responding to a military solicitation looking for higher muzzle velocity than current 5.56 NATO ammo. That was five years ago. The prospect is still churning in Army circles, and in the meantime Federal pushed forward with a commercial use, a cartridge for hunters who hunt with short barrels and suppressors.

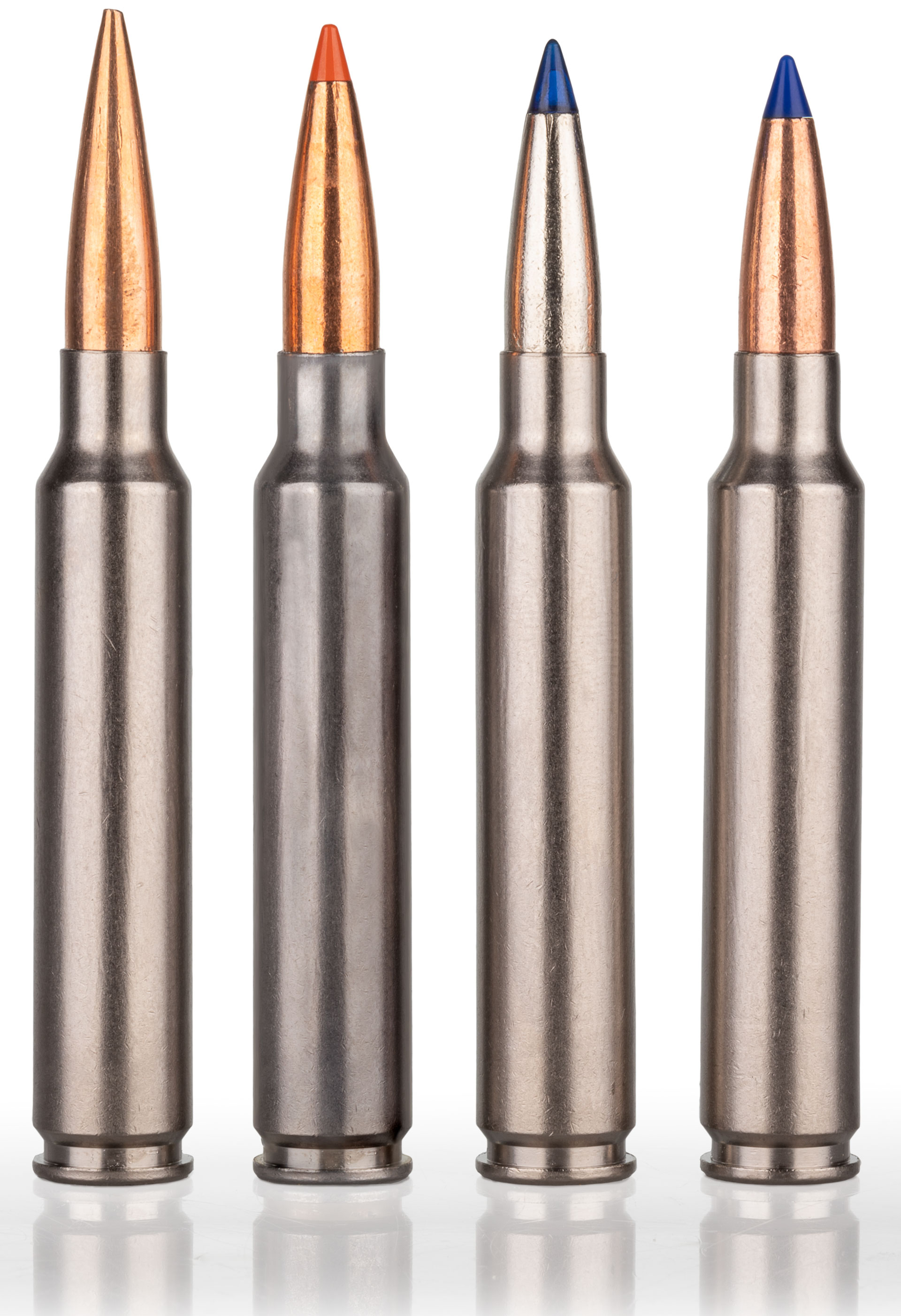

The headstamp on the sample ammo sent to me before the hunt simply read “FC 24.” Eighty rounds came in plain Federal Premium boxes wearing stick-on labels that read: “7mm Backcountry; 3000 FPS; 170-gr. Terminal Ascent; G1 0.645; G7 0.325.” (The 170-grain Terminal Ascent bullet is one of five loads being released by Federal. Others include: a 155-grain Terminal Ascent; 168-grain Barnes LRX; 175-grain Fusion Tipped; and a 195-grain Berger Elite Hunter. That’s a lot of flexibility. Twist rate is 1:8 inches.)

In Virginia, I fired a handful of rounds on the NRA HQ indoor range to confirm an average muzzle velocity of 2941 fps, and I created a drop chart. My rifle was a Gunwerks GSL action mated with a Revic riflescope, a rig the Cody company produced specifically for the hunt. I set up at a hundred yards because I wanted to use the Revic dial out West. To the fore-end I mounted an adapter for an Elevate bipod, but I made sure I could use my flip-out Bog sticks with the shape of the stock. I shot three, three-shot groups at a hundred that averaged .75 inch—very good for some of the first groups of new ammo and one of the first guns chambered in the cartridge. Then I walked it out on steel plates to 300 enough times to confirm my DOPE. Off to New Mexico I went with 35 rounds.

The cartridge is designed foremost for hunting. Its very name—Backcountry—evokes hunting. Like other modern 7mm cartridges I have used to take big game, namely the 28 Nosler and Hornady 7mm PRC, the 7 BC is built to take advantage of today’s high-ballistic coefficient bullets to flatten downrange trajectory, which is especially beneficial to hunters.

An apples-to-apples comparison of velocity, energy and drop at 300 and 400 yards paints that picture for hunters. I used an online ballistics calculator to produce a graph for each cartridge. I tried to keep factors similar. All three loads were zeroed at 100 yards at 8,000 feet elevation, as that’s where my elk hunt occurred, and I used G7 ballistic coefficients for each bullet. I picked a maximum distance of 400 yards merely to save space here. One can shoot longer than 400 but he should hope and hunt to avoid it.

The 7 BC with a 170-grain Terminal Ascent carries a G7 BC of .325. It produced an average muzzle velocity of 2941 fps from my 18-inch barrel. At 400 yards velocity is 2528 fps, and energy is 2,413 ft.-lbs. Drop at 300 yards is 10.33 inches, and at 400 it is 22.87 inches. The 28 Nosler loaded with a 175-grain AccuBond Long Range carries a G7 of .326. Muzzle velocity is rated at 2975 fps. At 400 yards velocity is 2561 fps, and energy is 2,548 ft.-lbs. Drop at 300 is 10.04 inches; at 400 it is 22.24 inches. The Hornady 7 PRC loaded with a 175-grain ELD-X carries a G7 of .347. Muzzle velocity is 3000 fps. At 400 yards velocity is 2608 fps, and energy is 2,643 ft.-lbs. Drop at 300 yards is 9.71 inches; at 400 it is 21.54 inches.

That’s about as close as you can get. True, downrange energy for the Nosler and Hornady loads is greater, but remember the above supposes factory muzzle velocities of 3000 fps from 24-inch barrels. Federal rates its load the same at the muzzle of a 20-inch barrel. Most importantly, remember the muzzle velocity I recorded came from a rifle wearing an 18-inch barrel.

The “hunting” part of this story is pretty short as my hunt lasted less than an hour. It was nonetheless exciting and worth recounting.

Before dawn on opening morning last Oct. 1, my guide, Bobby Duran of Frontier Outfitters, drove into a ranch owned by the Taos Pueblo just outside Angel Fire, N.M., where we planned to hunt all week if necessary. This land was purchased by the tribe to create a buffer from the rest of the world. It’s not used for anything, really, except some hunting. It is beautiful ground, and loaded with elk.

We exited the truck at 9,000 feet and listened. We walked downhill amid faint sounds of elk. Bobby called; a bull bugled—hey, that didn’t take long. Soon we spied the big fella drifting through the conifers on a parallel finger. The bull was headed uphill from his evening feed on alfalfa fields below us. He was about 350 yards away; not too far for a shot, but the problem was singling him out amid the trees and other elk. I couldn’t stay on him long enough to remain sure of a shot. Also, frankly, I knew if I hit him but didn’t drop him on the spot I’d never get another bullet in him, and he’d probably get away and it’d all be a mess, and I said as much to Bobby.

Moments later we’d moved uphill and settled into a cut bank on the edge of a meadow. I was seated, heels dug into the dirt with the rifle on my sticks as Bobby called again. The bull answered and we waited. Holy cow—he appeared below us, taking his sweet time moving uphill. Bobby ranged him: 250 yards. I cranked up to 4X, dialed the Revic turret for the distance then began to focus and breathe … and press. The bull whirled, sort of, and dropped. My gosh. I fired one bullet literally less than 45 minutes into a four-day elk hunt and dropped a 6x5. Hey, for all the hunts that have put me through hell and delivered exactly nothing I will never kick a gift horse.

The rest of the week I cheered on the other hunters, and spoke with Mike Holm about his company’s 7mm elk medicine.

Holm explained the increased pressure of the 7 BC is the result of the propellant. It’s an existing, commercial-grade powder but we can’t buy it off the shelf right now. It produces a different pressure curve than other powders, which reduces the recoil impulse amid 80,000 PSI. The kick of a 7 BC from a 20-inch barrel is similar to that of a 7mm Rem. Mag. or .300 Win. Mag. with a 26-inch barrel, in large part because less powder is used in the 7 BC.

Here’s another thing I learned: As pressure goes up, burn rate goes up. This means the gunpowder used to push an 80,000 PSI 7 BC bullet is extremely progressive-burning. The amount of pressure remaining in the barrel when the bullet exits has a huge effect on accuracy. Shortening a barrel too much will cause a bullet to exit with so much pressure behind it shot groups become too dispersed, but not so with the 7 BC.

I mentioned that I thought of the steel case as a kind of “fourth ring of steel,” in line with the famous Remington ad campaign. When it introduced the Model 700 in 1962, Remington promoted the rifle’s “three rings of steel” surrounding the case head that protected the shooter from harm: the enclosed bolt face, the barrel shank and the forward receiver ring. The steel case of the 7 BC seems to me to add a fourth ring at the foundation of the whole shebang, and that can’t be a bad thing.

Then Mike said, “You know, we can do this with other cartridges.” That spurred some thoughts. This technology likely will not be limited to this new big-game cartridge. The Army is interested in the concept, and hunters with old rifles should be, too. Imagine a whiz-bang 6.5 Creedmoor or .308 Winchester. The rifle must be built to modern standards, and, foremost, SAAMI would have to reconsider other pressure limits. But with such “improved” cartridges we might expect velocity and energy gains of about 20 percent. That’s huge. For now, to be safe Federal released the technology in a new cartridge to ensure it will be fired only through new guns.

But what piques my interest most about the 7mm Backcountry—besides the “free lunch” one gets while using a short barrel with a suppressor—is the prospect of a practical rig for backcountry hunters (see what I did there?). Imagine heading into the wild with the smallest form factor of a hunting rifle possible: a bolt-action with all the bells and whistles and a 16-inch barrel and a folding stock that’s maybe 24 inches long when stowed. Pretty cool. On site, a hunter could pull the gun from inside his pack, unfold the stock, unfold the bipod, screw on the suppressor then settle in behind the gun, knowing full well he is not handicapped at 500 yards. If a guy who likes this cartridge saw a factory-built rig on the shelf … something like a cross between the Savage 110 PPR and 110 Ultralite Elite—yeah, I think he’d buy it.

Ahh, to dream. I’ve got 14 rounds left, and I know a guy who can get me some more if I want it.