The isolation of a small Vermont town is lost on somebody growing up there. If it’s all you know, then it’s your only reality.

Suspecting a bigger world out there, I tempered that reality with books. As a hunter I read all the great Southern writers—Ruark, Babcock, Buckingham and others—but they puzzled me. Their upland bird of choice was the bobwhite quail, and in my isolation I had never met anybody who had seen a bobwhite, much less hunted them. I didn’t have a clue about quail except that they were very small and lived in something called a covey. From the photos and paintings it looked like you hunted them in open country, which must be wonderful.

What puzzled me most was the way all those writers kept referring to the quail as a “gentleman.” That simply didn’t compute. How can any bird in America be “of noble or gentle birth, belonging to the landed gentry?” Or did they base it on the more accepted definition in which a gentleman drinks his tea with a pinky sticking out while politely chattering through clenched teeth with a British accent? Does a gentleman quail open doors for the lady quail? Do they smoke cigars and sip brandy after an exquisite dinner? Are they extremely polite to each other? I never could figure out what exactly makes a quail a gentleman.

Bird hunting in my part of the world meant ruffed grouse, and the ruffed grouse is anything but a gentleman. Our bird is a sucker-punching, bar-brawling, sociopathic trickster. It hides under cover and explodes beside you with a roar of wings as adrenaline kicks you in the guts. Grouse will duck and dive, toss out chaff and always keep a tree between you and their flight path. They might flush as soon as you step foot in the same country, or hold until your pants cuffs are tickling their wings.

That all depends on when you are the least able to shoot at them, which is something they have a knack for knowing. They live in the thickest brambles and will wait to flush until you are tangled in a fence, imprisoned by thorns or tripping on a hidden root. They won’t hold for a dog, but will hide, run or get into the trees, anything it takes to keep from getting shot. A day spent hunting grouse can beat you senseless and leave you feeling impotent and worthless. There is nothing “gentlemanly” about any of it. Hunting ruffed grouse is close-quarters combat with a four-letter soundtrack.

Because it was all I knew, I took that attitude to my first quail hunt many years ago, a short add-on to an Alabama deer hunt. It was an opportunity to finally check out this “gentleman” bird of the South. My goal was only to shoot a quail.

I was a bit annoyed when the dog first hit a point because when they handed out guns the only thing left for me to use was a full-choke trap gun with a stock that was cast for a long-armed, left-handed shooter. I turned the anger inward and stared intently at the ground in front of the pointer as I advanced.

When the covey flushed I turned the first bird to bits and feathers as soon as it cleared the dog’s head. I was a grouse hunter. In that world you shoot fast or not at all. I had no reason to think quail were any different. I forgot about the full choke.

The response I got from my host was anything but gentlemanly. He claimed I was impolite, shooting so fast. I still think the problem was that he missed and I didn’t. Normally that’s not an issue among gentlemen, but my host was the guy who had handed me the trap gun, grabbing the best shotgun for himself.

It wasn’t photogenic. I had my first quail, but I still had not hunted quail. At least not properly.

The next time it was much different. I had a well-fitting shotgun, good dogs and companions without shoulder chips. It was the first of many enjoyable hunts and now I can say that I understand quail hunting, at least as well as any Yankee can. I still don’t get the part about the birds being gentlemen, but the rest of it has me clutched firmly in its grasp. I am addicted to hunting quail, so when Benelli’s Joe Coogan suggested I meet him in south Georgia for a few days of hunting, I couldn’t agree fast enough.

We were going to test some new shotguns and film a segment of the “Benelli on Assignment” TV show. Joe is an old friend. We have shared many hunts, and he has never insisted I use an ill-fitting trap gun to shoot quail, so I expected good things. What we found may be the last great place for quail hunting—a traditional hunt in South Georgia.

Tommy Newberry was awarded the third commercial hunting preserve license ever issued by the state of Georgia, in 1960. That means Quail Country has been hosting bird hunters for more than five decades. That’s a lot of time to build traditions and a lot of experience with bobwhites. Today Quail Country is run by Tom’s daughter Kay and her husband Dr. C. Paschal Brooks. It costs a bit more to hunt there than the $25 per day Tommy charged way back when. Today the hunters stay in a first-class, 14,000 square foot lodge, built in 1995. The food is outstanding and the hunting, on 3,500 acres of managed land, is as good as it gets. Like any commercial operation that is surviving today, they use a mix of released and wild birds. This works well to provide plenty of shooting opportunities while maintaining the proper quail hunting experience. Even after inflation, I think today’s rates are a better deal.

Like any hunting operation, they take great pride in their kennel and dogs. And that pride is justified, as they have some of the finest dogs I have ever hunted over. In addition to the excellent pointing dogs, they use English cocker spaniels to flush the birds. This works out great because the hunter does not have to move in to flush the birds. He can stay in position, without his feet and balance out of whack on the flush. It also eliminates the guides moving forward to flush the birds, which makes me nervous.

It turns out the essence of quail hunting in south Georgia is about a lot more than just shooting birds. But it takes a level of maturity to understand and appreciate that, a maturity I lacked 30 years ago. Quail hunting is a frame of mind, and it is an immersion experience. You can’t hunt quail casually and appreciate the meaning, you must surrender to it fully.

Most will say the essence of quail hunting is about the dogs working or about the flush or shooting well, but that fails to capture the deeper truths.

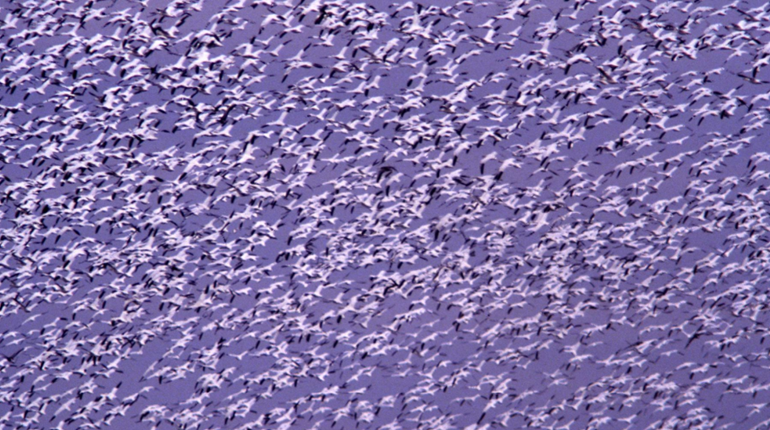

Quail hunting is about riding quietly through the early-morning mist, lost in thought while the dogs whine in anticipation in the box behind you. It’s watching the mist float through the oaks and Spanish moss then watching it lift to reveal the milo fields. It’s the scent of dogs wet with the dew, empty shotshells and the Georgia woods on a cool day. It’s the explosion of a covey flushing, the confusion while you try to pick one bird rather than flock-shoot, and fail. It’s the excitement of a dog suddenly going “birdy,” watching as his nose vacuums the ground and his tail keeps a stiff rhythmic beat that turns faster and faster as the trail grows hotter. You marvel at his focus, his determination, his single-mindedness then, even more, at his discipline as he locks into a catalog-perfect point. What must it take for that dog to hold, fighting eons of evolution where every instinct tells him to pounce forward and grab the bird? His companions are backing, honoring his point, fighting their own demons while the flushing dogs are coiled springs waiting for their orders. To us, the man with the whistle is the guide; to them he is God.

Quail hunting is about the prickly excitement of approaching a brace of dogs on point. Every nerve is tingling, every muscle ready to explode. The shotgun feels electric in your hands and your mind is focused down to a single, square yard of ground in front of the dog’s nose. Nothing else in the world carries any importance, just the dogs, the birds and you.

The flushing dog runs in, the world explodes and the ground spews birds. Then, magically, time slows. You pick a bird as the gun finds its own way to your shoulder. There is recoil and noise and the bird tumbles, leaving behind a puff of floating feathers. Your eye finds another bird as the gun tracks his flight and when it’s right you send a load of 8’s down the second barrel, knowing even before the primer fires that this was a clean and true double. The best part of hunting quail is hearing your buddy softly say, “nice shooting,” and knowing he means it.

Quail hunting is pointing dogs, double guns and stiff canvas pants. It is the metallic thunk a shell makes as it drops into a break-action shotgun. It’s the feel of a good shotgun in your hands. It’s the smell of gun oil, burned powder and wet Georgia clay. It’s the way your feet hurt at the end of the day, a good hurt that reminds you that you earned your birds. It’s the scent of muddy dogs and the taste of cold water when you are so thirsty it hurts.

Quail hunting is starting the day with eggs and grits and ending with cooking that is so good you don’t care about anything else. Quail hunting is your full game bag bouncing on your back as you walk to the truck. It’s sitting with friends watching the sun ramble west, too tired to even unlace your boots, recharging, while sipping something amber and soothing.

It’s good friends, good guns, good dogs and knowing that life gives you only a handful of perfect days.