As I putter around fooling with old stuff I often find myself reacquainting myself with nearly long forgotten skills. In the old days miserly handloaders—a redundant term—would often anneal the necks of their brass cartridge case hoard in order to extract an additional loading or two before reluctantly retiring the eight-cent case. Today relatively few handloaders take the time to anneal their case necks. It is a boring and tedious chore, and given the volume of shooting done by many modern shooters, annealing case necks is simply impractical.

As I putter around fooling with old stuff I often find myself reacquainting myself with nearly long forgotten skills. In the old days miserly handloaders—a redundant term—would often anneal the necks of their brass cartridge case hoard in order to extract an additional loading or two before reluctantly retiring the eight-cent case. Today relatively few handloaders take the time to anneal their case necks. It is a boring and tedious chore, and given the volume of shooting done by many modern shooters, annealing case necks is simply impractical.

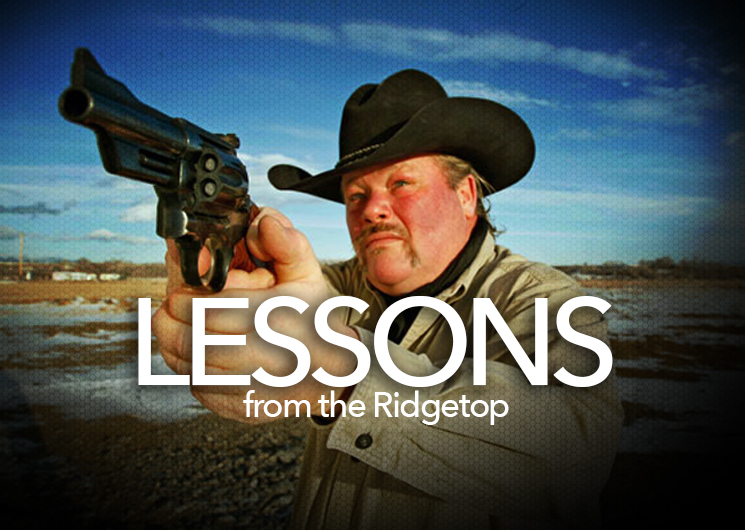

However, as I said at the beginning, I am fooling around with the old stuff—specifically the .45-90-2.4 Sharps cartridge and black powder, along with bullets the size of your thumb. In a couple of weeks I’ll be joining The Shootists in Raton, N.M., and several of us will be going up against the 1,123-yard iron bison on the silhouette range. The batch of cases I am using have been fired once, and the sizing, expanding, bullet seating—anything that moves the brass—work-hardens the case at its neck. I was initially skeptical of this whole annealing process, so I asked some guys with a lot more experience than I have to explain the logic and necessity of annealing.

One Country Gent (his online moniker), of Ohio, stated the reasoning succinctly, “Case neck annealing helps maintain consistent neck tension on a loaded round. As cases are sized and fired they are constantly flexing and work hardening. (similar to bending a wire back and forth till it breaks) This also affects how well the cases seal to the chamber.” He further stated that I could verify the effectiveness of annealing by taking 20 cases from the same lot; annealing 10 and loading the other 10 without annealing, Shoot all 20 at one sitting, recording accuracy and characteristics (like effectiveness of sealing the bore based upon how dirty the exterior of the case is); repeat the process until the cases begin to fail—split or head separation. That would take quite a while, so I’ll defer to his experience in the matter.

There are several methods used to anneal case necks, differing primarily in productivity and, to a lesser degree, uniformity. One can buy or build a jig the only allows the first half-inch or so of the case neck to be heated. The time honored one—and what I am using for now because I don’t have the time to build a jig and am too stingy to buy one—is to place several empty cases with the spent primers removed into a cake pan about half filled with water. It should be obvious as to why one would not anneal cases that are live primed. I removed the primers in order to allow the water to fill the bottom of the case and keep it from bobbing around in the water. Heat the top 1/2 inch of the cases with a torch as evenly as possible; when it glows orange, remove the heat and tip the case into the water to cool. The purpose of the water is two-fold: It prevents the heat from crawling to the head area of the case and ruining it, and cools the neck so that it can be handled—removed and set to dry while replenishing the pan with fresh cases—with bare hands. There is more to learn about this annealing thing—mostly as to how to increase productivity—and I think I’ll see if the powers that be here will allow me to further explore it in a full-length article.

Annealing isn’t just for old charcoal burners. Many ammo manufacturers anneal virgin case necks to reduce the scrapping of new cases with split necks during the loading process. Too, I am hearing rumbling of accuracy buffs using case annealing to maintain uniformity of bullet tension and sealing of the bore and chamber in modern ultra-high-velocity cartridges. When your passion in life is the zero-inch group, nothing is too tedious or over-the-top to achieve that objective.