The uninformed think that a black bear is the bully of the woods, smashing and crashing his way through life. The truth is a black bear is a ninja, silent, stealthy and unpredictable. Bears have a spooky way of just appearing, as if by magic.

It’s early, only 4 p.m., and it’s unusually hot for mid-September, well into the 80s. No self-respecting bear should have been here. The sun is high and bright and here in the shade it’s too hot even for the mosquitos. My worn-out back is hurting but I ignore the pain and focus on sitting still. You see, sitting still is the price and the penance a bear hunter pays. Bear hunting over bait in Maine is about waiting. It’s about hour after hour of sitting still. If you move, even one time, in all those hours, it’s all but guaranteed it’s the moment that there will be a bear there to see or hear you.

The big, old and educated bears often have a spot, a sniper’s nest where they wait and watch. You won’t see him, but if you move, he will see you and the game is over. So you arrive early, sit quietly and don’t move. Every day, hour after hour, whatever it takes. That is the challenge of bear hunting. You sit and you do not move; even through all those “preliminary” hours when you know for sure no bear will appear. After all, everybody knows that bears, if they show at all, come only at last light.

Except black bears don’t follow the rules.

It’s day three of my six-day Maine bear hunt and I have not yet seen a live bear. Squirrels, camp robbers, blue jays, spruce grouse, chipmunks, raccoons, ruffed grouse, ravens, mice and bald eagles I have seen, but not a bear.

Wishing I had taken more ibuprofen, I try to think happy thoughts and ignore that dusk is so many hours away. Sweat drips into my eyes, making them sting. I blink and there is a bear standing 20 yards away.

Off in the distance I hear a shot. Then another.

■ ■ ■

This all started when Dean Wetherby bought a .35 Whelen rifle. He was at my house gathering brass and handloading tips when he mentioned a bear hunt. “A high school buddy of mine, Matt Whitegiver, owns a company called Eagle Mountain Guide Service in Maine,” said Dean. “I think I am going to book a bear hunt for this fall so I can use this rifle.” My fall was pretty open so I called Matt and booked myself. Word got around and the thing grew to six of us, which filled half the camp.

Matt’s Wilderness Lodge is located off Route 9, an hour east of Bangor and just 35 miles from Canada. The coast, including Bar Harbor with its hordes of tourists and $35 lobster rolls, is about an hour to the south. But in terms of Maine culture, this camp is a universe away.

The large eastern coastal region of Maine that covers Washington and Hancock counties is called “Downeast.” That’s said to be because the ships heading there from Boston were sailing east and downwind. It is perhaps the most diverse part of Maine. It’s just a few miles from Grand Lake Stream, one of the world’s premier fishing destinations for landlocked salmon. In fact, Matt guides on the lakes and I spent a fantastic week in May fishing with him for salmon and smallmouth bass. I also fly-fished on Grand Lake Stream for salmon, which was a big bucket list checkoff.

I might also note that I shot my first black bear near Grand Lake Stream back in the early ’80s. When my .44 Magnum handgun roared in the last hour of the last day, it started a love affair with bear hunting and all its multitudes. Bears are in many ways my totem animal; our journey together started just a few miles from where I was hunting 40 years and many bears later.

Matt’s Wilderness Lodge is a world apart from the coast and its tourists. It is so remote that even as it sits close to a major highway, a generator supplies its electricity. The lodge is a large, rambling building with a checkered past. Built for Jackie Gleason in 1963, the Wilderness Lodge was a getaway for the golden horde of Hollywood, including John Wayne and many others. Local legend holds that after a few trips here in the height of black fly season the place soon lost its luster for the beautiful people. At one point the lodge was a brothel and did a booming business with loggers, fishermen and straying husbands from Bangor or Bar Harbor. Matt guides for deer, moose, bears, upland birds and fishing from here and to me it feels like home. Both times I’ve been to this lodge I was sad to leave, which is a clear indication that it’s a good place.

Matt reserves the last week of the bear season for Special Operations Wounded Warriors (SOWW; sowwcharity.com). He and his wife, Lisa, donate a lot of time, money and profit so that those who have fought and bled for our freedom can have a chance to know they are appreciated. It’s a lot more than that; it’s a week with their brothers, a week where they can heal, learn they are not alone and maybe find a path back to the world. After talking with a few of these guys I realize that what Matt is doing with SOWW is changing and even saving lives. Those guys gave everything and our government has let them down. SOWW and Matt are working to make some of it right.

Dean and I talked often through the summer about his new rifle and the handloads he so carefully crafted. He was very excited about the possibility of shooting a bear with the Whelen. Matt doesn’t have many rules, but checking zero is mandatory. Dean was coming back as I was walking to the range. He was muttering and cursing as he passed. I soon recognized that he suffered from The Gun Guy’s Curse, a vile and troubling affliction resulting from owning too many similar rifles.

In the rifle case he carried was a beautiful Remington CDL rifle in .280 Remington. It’s an exact copy of his .35 Whelen, which, as it turns out, was in the safe back in Vermont. Seems that .35 Whelen ammo doesn’t fit well in a .280, no matter how hard you try.

Like I said, though, he is a gun guy, so of course he had a spare rifle. Dean hunted the week with his .358 Winchester. I will say that Grasshopper has learned his lessons well on rifle cartridge choice and he has found enlightenment for the superior qualities of the .35-caliber bullet.

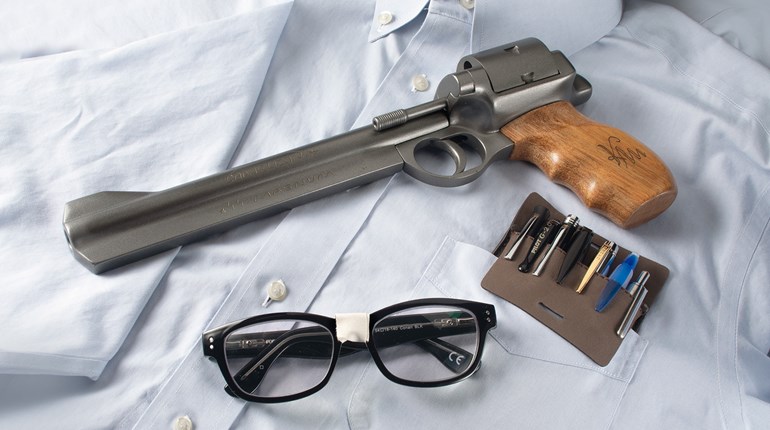

The truth is, we had multiple .35 Whelens in our group. As it’s one of my favorite cartridges, it cut me to the marrow leaving home without one. But, we gun writer types rarely use our own rifles and this gave me an opportunity to hunt with a gun I had picked up about a year prior. I had a Ruger No. 1 Medium Sporter in .45-70. I topped it with a Leupold 1.5x5 scope and fueled it with Barnes ammo with the 300-grain TSX bullet. In my never humble opinion it’s close to the perfect rifle and cartridge for this hunt. It’s short and compact so it handles easily in a blind, yet it hits with the authority of a bunker buster bomb. Bears up close in thick cover never give you a second shot anyway, so the single shot aspect is moot.

■ ■ ■

I waited until the bear’s head was behind a bush and slowly raised the rifle into position. The bear stepped out into the small open area, looked at me and then laid down. At the shot the impact caused him to roll over, 360 degrees, landing on his feet. In a small fraction of a short second, he disappeared from sight. For a moment, I was starting to question if he was ever there.

Another of Matt’s rules is to stay in the stand after the shot. I knew they were probably tied up with those other shots I’d heard, and I can track well enough. So I stuck with my core belief in all things that rules are simply suggestions. I can beg forgiveness later.

I found blood at the shot location, but in just a few yards it petered down to nothing. I stood listening and smelling the air, hoping for a clue. Then I saw a dead tree about 4 inches in diameter 20 yards off to my left. It was painted bright red. From there the short trail was evident, and just a few yards past the tree was a nice black bear boar.

The author and his party went five-for-six on bears. He sat patiently on his perch in the Maine woods with his Ruger No. 1 Medium Sporter in .45-70.

The author and his party went five-for-six on bears. He sat patiently on his perch in the Maine woods with his Ruger No. 1 Medium Sporter in .45-70.

The other shots were Bryan Mason and Jim Majoros. We had all taken boars and mine was the longest track at about 75 yards. What I didn’t hear was one more shot from another guy in camp, a guy who clearly does not read my writings about cartridge and bullet selection.

Matt called in the “Tracking Ladies” and they tracked the bear until late that night. They were back on the track at first light. By noon they had gone several more miles and determined that the bear was not fatally wounded. This is one of the great things about tracking with dogs; you can usually get a resolution. Not always the one you want, but at least you can sleep at night. Well, maybe in a few months you can.

Any discussion of this situation on the internet always will lead to some “expert” stating, “It’s all about shot placement.” What he doesn’t understand is that once in a while it is not. I have seen several catastrophic bullet failures over the decades, almost universally as a result of a bad choice of cartridge and bullet. While I can’t be sure with an unrecovered bear, I suspect that happened here. High-speed cartridges and fragile bullets shooting big game uber-close can lead to big problems.

After the Wednesday night flurry, our group of six hunters had five bears as Phil Baker and Brent Cassavant had scored on the first night. Brent’s bear was a 250-pound dry sow, quite large for a female. The first bear he had seen in the wild, it showed before he heard the guide’s truck leave and went to sleep under a tree, only 30 yards away, but presenting no shot. Brent watched it for three and a half hours before it finally stood up and gave him a shot. This kid has nerves of steel.

■ ■ ■

I used the rest of my time exploring the area, including the miles and miles of blueberry barrens behind camp. I found several remote brooks and rivers to fish and caught a few brook trout. I fished in a lake near camp and caught a bunch of smallmouth bass and a few pickerel. I ate like a pig, slept like a log and enjoyed the camaraderie that only a good camp can generate.

While riding with Matt checking bait locations I picked his brain a little about how he hunts.

“Many of my stand locations have a long history,” Matt said. “We have hunted some of them for decades. Momma bears have brought their cubs there for years and some of those cubs grow up to be big bears that keep up the family tradition of visiting our stands. It’s not unusual to shoot multiple bears off the same stand. If there is continued activity we often keep hunting the stand.”

The stand where the bear was wounded had already produced two good bears this season. I could see the blood stains on the leaves from both of the first two bears in sight of the treestand while we were looking for a blood trail from the wounded bear. All three were large, adult boars.

“Often when you shoot the boss bear, his rivals, who are not necessarily smaller, see that as an opportunity to come to the bait,” Matt continued.

“I notice that a lot of the stands are along small streams,” I said. “Why is that?”

“A couple of reasons,” Matt replied. “The streams are the low point of that land and bears love to follow them. They probably find food there, but it’s also a good travel corridor. Most of these are small, lazy streams so they don’t make a lot of noise. Also, the loggers have to leave a section of land on both sides of the stream untouched as a buffer to prevent erosion. The resulting thick cover is attractive to bears. Even as the clear-cuts grow back the bear will stick with his habit of traveling along the streams. I put stands there because it’s much easier to draw a bear into a place he was planning on going to anyway.

“I am using more and more ground blinds these days,” Matt continued. “One trick is if the bear is used to looking for the hunter in the treestand, I move them to a ground blind off to the side. We shoot a lot of smart old bears that way.

“The hardest thing we deal with on these hunts is morale. If hunters are not seeing much they start to second-guess us. They lose faith in their stands. But, I think that a bear can actually become accustomed to the hunter. Perhaps the bear has been around a few times and he circles and smells the hunter. But, nothing bad happens so after a few days the bear thinks that maybe he is depriving himself of all that good eating for nothing. He decides to grab a snack and the hunter is suddenly very happy. Still, making a hunter believe in the stand is the toughest part of my job.”

I know personally from years of doing these kinds of hunts in Maine and Canada, as both a hunter and a booking agent, that it can be very slow with nobody seeing bears for several days. Then you get a “bear day” where several hunters in camp all connect. Look at when I shot my bear, for example. We had three bears killed and another shot at in less than a 30-minute timespan. This happened hours before dark when it was very hot and the sun was bright. Bears should not have been moving. The stands were miles apart, but for some inexplicable reason the bears all decided to show up at the same time. Why? Nobody knows.

“But, what I do know,” Matt said in answer to that question, “is that the hunters who listen to me and sit still and stick it out are the hunters who are there when the bears finally show up. You just gotta have faith.”

Dean was a believer and the only hunter in our group still carrying an un-punched tag. He had stuck with his stand for six days. Matt had a huge bear run across the road in front of his truck, heading for Dean’s stand the day before. On the last day the huge boar stood facing Dean, with a tree blocking his vitals, for what Dean said was “only about a century or two.” Then he turned and disappeared into the thick Maine wilderness.

I talked to Dean a week to the day after this happened. “I am getting a lot of work lined up for this year and saving my pennies,” he told me. “As soon as Matt gets home to phone service I am booking again for next year.”

I believe I may join him. I think, though, to cover the bases I might toss an extra box of .280 ammo into my truck, just in case.

Downeast Hunting

In spite of thunderstorms and brutal heat Matt Whitegiver produced bears. His camp feels like home and it was one of the best weeks of hunting I have had in years. Book a Maine adventure with him: Matt Whitegiver, Eagle Mountain Guide Service and Wilderness Lodge; 207-537-5282;[email protected]; eaglemountainguideservice.com; facebook.com/Matt.Maineguide.

The Tracking Ladies

I asked Matt Whitegiver why he preferred to have his stands so close to the bait. “Because it cuts down on our missed and wounded bears,” he said.

But, “stuff” still happens now and then. Black bears are intimidating critters when they show up. If you have never seen a bear before, after days of waiting you begin to think they don’t exist. Then a bear suddenly shows up and things become very real, very fast. Sometimes fear and surprise play a role and bear fever is all too real. The result is the hunter often rushes the shot. It’s not uncommon to completely miss a bear with a scoped rifle at archery distance. That’s OK, no harm, no foul. But when a bear is wounded the game changes. Bears are notoriously hard to track, and in days past wounded bears that should have been recovered often were not. Today, Matt calls the Tracking Ladies.

Susanne Hamilton and Lindsay Ware work together when they can and alone when they must. They are both members of the United Blood Trackers and are Registered Maine Guides. They call what they do blood tracking. Their highly trained, wirehaired dachshunds work on a leash to follow the wounded critter. Even if the blood trail peters out, the dogs know the exact bear they are after and will stay on the track.

Not only bears, but deer, moose and even at least one bobcat have been recovered. These two women live for this and work for donations only, which means in the end they lose money. During the hunting season they are incredibly busy. They try not to say “no” to anybody and they are in very high demand.

I listened to a radio interview with the two of them and one thing stuck with me. Susanne said: “We get very skinny this time of year.” Both women are in phenomenal physical shape. The most common thing you hear from anybody tracking with them, even from young, tough guides, is how hard it is to keep up with Susanne and Lindsay.

When asked about success rates Lindsay put it well. “We are nearly 100 percent successful,” she said. “However, we define success as finding a resolution. Of course, we love to find the bear (or deer or moose) so that the hunter can take it home, but we often follow until we know that the animal is not mortally wounded. We also know that it’s not hiding under a brushpile dead, but not recovered. We define success as getting the answers. Either the bear is recoverable or it is not, but either way the hunter has some closure.”

Wounding loss is devastating to the hunter as well as the game. In this big game hunter’s opinion, the Tracking Ladies are doing God’s work. I strongly suggest you find a blood tracker near you well in advance of needing one so you know whom to call when you need help. To do that, visit unitedbloodtrackers.org.