I never thought I’d see a pterodactyl, at least not short of a Steven Spielberg flick. I didn’t think I’d shoot one, either—but there one lay, in a crumpled heap some 30 yards from the blind, felled by a shot from the still-smoking barrel of my Franchi Affinity. And some of his friends were still falling from the sky, including one that came down with a heavy, wet plop in the mud just a few feet behind us. We’re killing dinosaurs, I thought. Well, not quite. Neither the pterodactyl nor the sandhill crane—which is what we were actually hunting—is a dinosaur. But if you’ve ever hunted cranes, you’d understand how prehistoric the affair feels.

Bear with me, now. For as long as man has walked Earth, we’ve hunted the other critters that call it home—and some of them, in turn, hunted us. Our ancestors learned how to kill creatures great and small, from all corners of the animal kingdom. One thing our species never had to tango with, though, is a dinosaur—which is good, because they’d have made short work of the lot of us. Even so, it’s not uncommon for modern man to wonder just what it would have been like to hunt the great beasts that once roamed our planet. Sure, some will say that hunting alligators in the American Southeast or big ol’ crocs on the rivers of Africa qualify. I respectfully disagree—heck, the damn things have been around longer than dinosaurs. Give them some credit. If you’re looking to feel like you’re hunting something out of “Jurassic Park,” it’s the sandhill crane—with its long, pointed beak, sharp talons and spine-tingling rattle-like call—you’ll want to pursue. Scientists do say that the last dinosaurs evolved into modern birds, after all.

Meet the Crane

It’s worth noting that I didn’t visit the Great White North expecting a crane shoot—it was something of a surprise. We were joining Max Cochran and his team from vaunted waterfowl outfitter Habitat Flats for what was originally meant to be a traditional Saskatchewan waterfowl adventure. You know: ducks, honkers—the usual suspects. But when my hunting party arrived at camp, we were told to be ready to hunt the infamous “Ribeye of the Sky.” As it happened, the sandhill cranes hadn’t yet left Dodge for the warmer skies down South, and we were going to take advantage of the opportunities they were presenting us. Waterfowlers are hunters of opportunity by nature, after all—you hunt the birds that are moving, or not at all. And so the hunt was on.

The first thing most of us had to do was get a little more acquainted with our prey. First and foremost, the sandhill crane is a big, slow-moving bird. Its dark gray body and red forehead aren’t hard to pick out, especially given that the wingspan on the greater sandhill crane can extend beyond 7 feet. To put that in perspective, go ahead and look down at the ground for a moment and gauge your height. Unless you’re Shaquille O’Neal, there are sandhill cranes that have wingspans wider than you are tall. These are long, lanky birds. Though their bodies still only typically weigh between 8 and 10 pounds, they’re an impressive sight in flight. And, boy, can their call send a chill down your spine.

It’s not uncommon for a group of waterfowl hunters to debate just what fowl’s cry they’ve heard in the distance, before the respective birds have gotten close enough to be properly identified. With sandhill cranes, there is no debate. The trumpeting rattle they produce is as identifiable as it is eerie. They’re darn loud birds, too, compared to their feathered friends. The first flock of cranes I’d ever seen decoy sounded like they were about to land on us—but in reality, were still more than 100 yards out. One of the more experienced crane hunters in the blind that morning was the first—but not the last—person I heard refer to the great gray ghosts descending on us as “prehistoric.” And yes, technically they are prehistoric, by human standards. Over the years, crane fossils have surfaced that are believed to be millions of years old. But the modern sandhill crane still looks like something that’s out of time. And they act like it, too. You don’t want to cross paths with a wounded crane, no sir.

Don’t believe me? You’d be wrong. A wounded sandhill crane isn’t easy to deal with, indeed. Granted, no wounded fowl is particularly cheery, but you don’t often see a hardheaded hundred-pound yellow Lab break off a hobbling Canada goose. With their long, pointed bills—designed to suss out their favorite meals, but adept at sticking hunters and dogs alike—sharp talons and aggressive nature, sandhill cranes make for a nasty customer. Whereas you’re likely to see a goose that’s leaking oil get up and try to make a run for it, a sandhill is just as likely to pop up looking for a fight. It doesn’t take dogs long to learn they’re better off leaving crippled cranes alone. And, sure enough, on more than one occasion I saw a monstrous yellow Labrador named Cash barreling toward a downed crane, only to break off at the last moment, when the bird sat up and reared its head back to strike. The dog, he changed birds in a hurry. His owner, our guide, grimaced, took a long look at his scarred hands—reminders of previous crane encounters—and set off to spare his pup the trouble. Retrieving a pterodactyl may have been simpler.

Where and How

It’s likely that many of the waterfowl hunters on either coast have limited experience with sandhill cranes—some of them may even be surprised to hear that you’re allowed to shoot cranes at all. But folks in the Central Flyway, and in some cases the Mississippi Flyway, will find the practice somewhat more familiar. Though I did my crane hunting in Saskatchewan, domestic operational hunting seasons are held annually in dozens of states throughout the country. The when and how varies greatly from state to state—all limit season length, and many closely control the zones in which you can take cranes. The Texas Panhandle—where many sandhills winter beginning around Thanksgiving—remains a hotspot if you insist on remaining in the Lower 48, with its three-bird bag limit per day and extensive season. We were allowed five a day during my stay in Saskatchewan.

And though some will pass-shoot cranes, that wasn’t on our radar. Part of the glory of waterfowling is that you never quite know what’s going to fly over your blind, which is how I’m sure quite a few sandhill cranes and the odd swan (in states where swan hunting is legal, that is) meet their demise each year when hunters take advantage of the opportunity presented and pass-shoot them. There’s nothing wrong with that. But once you’ve decoyed cranes, you’ll want to do it again. And again.

I asked Dusty Brown, a veteran sandhill crane hunter, who joined us as a guest of Sitka Gear, for his advice. The most important thing? Concealment.

All waterfowl live and die by their eyes, but the sandhill crane is especially choosy. Dusty’s advice is to find natural concealment, like willow pockets or a hedgerow. Otherwise, everything’s for naught—no matter how fancy your camouflage or ghillie suit may be. Blind style, camouflage style, they all come second to hiding in something natural. In Saskatchewan we often backed an A-frame up to a hedgerow, and spent no small amount of time ensuring it was properly enveloped by nature before we crawled into it.

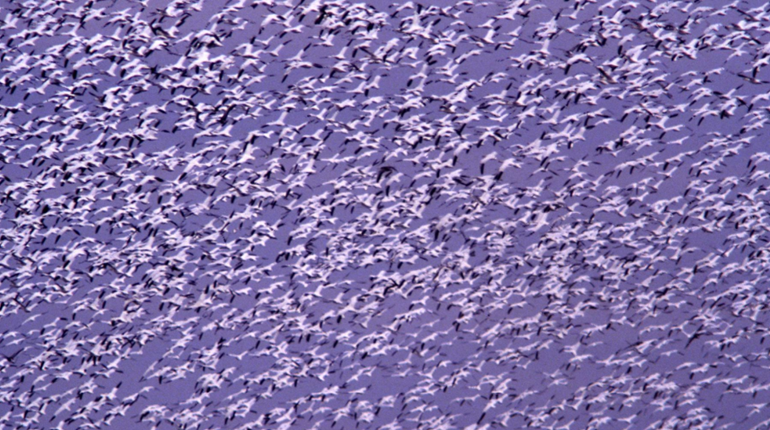

If you’re hunting sandhills up North, as they’re beginning their migration, you’ll be hunting smaller flocks that are on the go. By the time they reach Texas and other wintering grounds, the cranes can build up into flocks that approach 10,000 birds. They’re a little wiser by the time they get to warmer climates, too—being shot at the whole way south tends to educate birds a little bit. Still, the strategy remains the same, wherever you may be: Find the birds, find yourself a hunting ground that provides ample concealment, set up the decoys and try to call in the buggers. When Dusty started hunting the species back in 2001, he and his buddies used homemade decoys, which sometimes amounted to little more than a gray rag on a stick. Nowadays, you should be able to find sandhill crane decoys with a little poking around. Calls are common, too, though Dusty still utilizes a Bill Saunders goose call that he’s tweaked to produce the desired results.

The challenge, obviously, is finding birds that are ready to work. After getting to a state that allows you to hunt cranes, that is. For the uninitiated, it’s an adventure waterfowl hunt that I’d wholeheartedly recommend.

Perhaps what’s most rewarding about hunting the sandhill crane is that, so long as you’re lucky, there’s no shortage of other birds in flight, too. On our final morning, we were a bit late getting to our hunting grounds—but that didn’t stop us from limiting out on ducks and cranes alike. In just less than 45 minutes. They call Canada the waterfowl Mecca for a reason, folks. Just watch out for dinosaurs.

Habitat Flats

To book a waterfowl (and crane) hunt with Habitat Flats, call 660-973-3805 or click here.