Through our night vision goggles around midnight, we spotted the hogs, seven humped figures strung out along the back of a field. Jay Coleman switched off the pickup’s ignition and let the truck glide to a quiet stop on the gravel road, the feral hogs a good 500 yards away and oblivious to our presence.

Attached to helmets, we each wore ATN PVS-14 night vision goggles, which gave our world a green tint. I carried an LMT AR chambered in .223, a small Crimson Trace CMR-201 IR laser atop its rail. Rifle at port arms, I followed Coleman as we slowly made our way over the soggy field. I kept waiting for the hogs to dash off, but they continued feeding, noses to the dirt, until we were within 50 yards.

I felt that nervous twitch. I was unfamiliar with the night-vision setup, unsure about using the laser for aiming and somewhat in disbelief as to how close we were to the pigs. Was this really going to work? Coleman stopped, ushered me to the front, reached over to the rifle and snapped on the Crimson Trace.

I pictured the laser slicing into the night air, and all I could think of was the movie “Star Wars” and a crimson light saber. I dropped the muzzle and placed the dot on the shoulder of the nearest hog, eased off the safety and began firing.

Once you start, keep shooting until the hog drops, Coleman had told me in the truck, then move on to the next one. I wore ear plugs, so I couldn’t hear whether my shots were hitting. I thought I was missing because that first pig kept running. So I kept shooting, laser dot stabbing at the black hog. It toppled over at my fifth shot. (I later learned I drilled the boar four out of five times).

I flicked the dot onto another hog, firing as it ran to my right. He dropped with just two shots.

Then I swung the rifle to my left, lined up a hog on a full-tilt scramble, feet flinging up mud as he headed back from where we had approached. I squeezed the trigger, trying to keep the red dot on that twisting body.

“Don’t shoot my truck!” I heard Coleman yell through my ear plugs.

I kept swinging the rifle but released the trigger, moved the laser up and over the outline of Coleman’s Toyota, then got the red dot back on track and finished off the third hog with two more shots.

Between my plugged ears and the green light of the night vision goggles, everything seemed to move in slow motion. But I doubt it took 10 seconds from the time I pulled off my first shot until the last hog hit the ground. Coleman let loose with a rebel yell and we high-fived.

I’d left my home in Wisconsin that very morning to kick off 2014 with an old-fashioned Mississippi Delta deer and hog hunt—already, I was up three wild porkers!

■■■

I took my first trip to the Mississippi Delta eight months earlier, for a turkey and hog hunt at the invitation of a women’s outdoor group. On that hunt, I met up with local crop farmer and hunter Jay Coleman; our personalities just clicked and we were good friends by the end of our first conversation. We quickly discovered a mutual love of hunting—especially hogs—and AR-style rifles, and we learned we both like to incorporate high tech into our hunts.

My host was Tim Saxton, a catfish farmer in his early 60s. Saxton had turned his former house into a hunting lodge and donated the use of the lodge to the women’s group. Saxton and I hit it off, too, and he insisted I come back for an early-winter deer hunt.

“You won’t have to worry about a thing,” Saxton said with a grin. “You can stay here, and we have places for you to hunt. Heck, we’ll even feed your Yankee self! Us rednecks, we’ll take care of you good!”

How could I pass up such an invitation?

Yazoo County lies on the eastern edge of the Mississippi Delta, the northwest region of the Magnolia State that lies between the Yazoo and Mississippi rivers. Famed for its rich, black earth and abundant agriculture, the Delta is a wildlife paradise, producing some huge whitetails. It’s the scene of a major hog population boom, too.

Driving around with Coleman, I saw thousands of geese covering cut-over ag fields, ducks clustered on oxbow inlets and swampy potholes, and hundreds of deer grazing in green openings. Chocolate-colored coyotes peeked out of the tall grasses, and hog sign was everywhere.

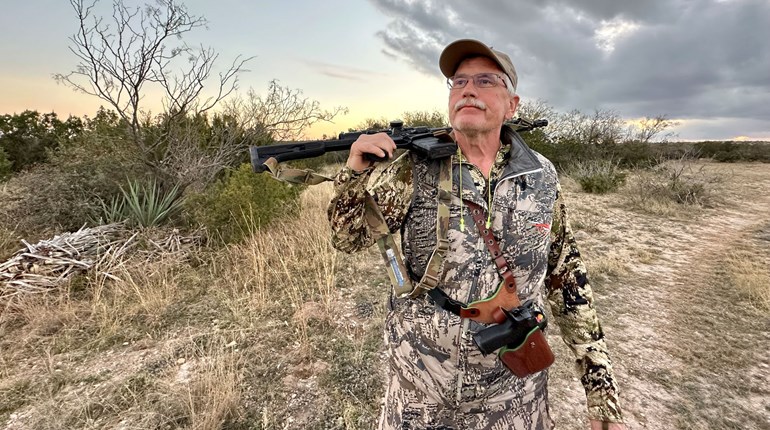

I had significant help making the hunt happen, especially from Mississippi-based Longleaf Camo and the company’s vice president of marketing, Mike Hurt. The Mississippi Tourism Department, the Yazoo County Chamber of Commerce and DRT Ammunition pitched in, too, not to mention good friends Coleman and Saxton, watching over my Yankee self!

■■■

After the first night hunting hogs, I spent the next several days trying to bag a Mississippi buck. I saw plenty of does, and a couple of young 4-pointers, but the only shooter buck was an 8-pointer. Or he could’ve been a 10. I wasn’t sure, because he never went slower than a full-out run after a doe, made a figure-eight in front of my blind at a couple hundred yards and then disappeared into the woods. No shot there.

The next morning, day three in Yazoo County, I sat in a blind atop a levee overlooking a green field. I’d decided to shoot the next nice doe I saw and get some backstraps for the grill when I noticed several brown and black stump-looking bumps among the palmettos on the far tree line. Then the bumps moved.

A group of eight hogs trotted into the green field, a good 280 yards away (I’d ranged everything from 100 yards out as soon as the light allowed). A tree sat between us. I could slide out of the blind and get closer, but I also wanted to see just what my shooting rig could do.

I was using Rock River Arms’ new LAR-8 X-series rifle chambered in .308 Winchester, topped with a Trijicon Accu-Point 2.5X-10X scope. The ammunition was new 150-grain rounds made by Dynamic Research Technologies (DRT), which specializes in frangible ammunition that essentially explodes inside the animal, dumping all its energy into a shattering punch.

The Rock River .308 had a stainless steel 18-inch barrel and a smooth two-stage trigger. Images in the Trijicon were clear and crisp. I had no doubt the ammo would do the job, having used other DRT offerings in the past.

Rifle, optics, and ammo were very capable. The shooter?

Spotting an opening in the bare tree limbs, I rested the rifle on my shooting sticks and scoped out a possible shot. Satisfied that the opening gave me enough space, I told myself that if the hogs framed themselves in that opening, I was going to shoot.

A couple minutes later, the foraging hogs drifted in front of that “window.” I picked out a good-sized black hog, figured the drop for the range would be about 7 or 8 inches, held the crosshairs up above the hog’s right shoulder and squeezed the trigger.

The X-series in .308 is a heavy rifle (9.5 pounds), and it absorbs recoil nicely—so much so my scope stayed pretty much on the hog as I pulled the trigger. I watched the animal rear up on its back legs, head held high for a long heartbeat, then collapse onto the green grass.I dropped back into my chair, barely believing the shot, half expecting the hog to jump up and run. But she didn’t, and the other hogs scattered into the palmettos.

■■■

Hunting isn’t simply recreation in the Mississippi Delta. Hunting’s what your family did, so it’s what you do—it’s a living connection to the past. Ken Smith is the sixth generation of Smiths to live and hunt in Yazoo County, and he’s a local history buff. A hundred-plus years ago, Smith notes, the fall hunting camp was the male social event of the year.

“You’d have generations of people hunting together, people not necessarily related to each other but who were connected by the hunting,” Smith says. “They’d load up their [horse-drawn] wagons with tents and blankets and basic supplies like coffee and lard and corn meal—but no meat! You were going to have to get that on your own.”

Hunting from horseback was preferred, he says, and running deer with dogs was very popular. Men and their boys stayed out for weeks at a time, hunting, fishing, telling stories around the campfire and passing on hunting traditions.

The Delta camp is still alive and well. Longleaf Camo’s Mike Hurt is in his early 40s, and he spent much of his youth in family camps. Deer hunting was tops, while campers also did some duck hunting and chased raccoons at night with hounds. Small buildings, portable trailers and tents would be home to 30 or more people at a time.

“It was a big community during deer season,” Hurt remembers. “My grandparents would pretty much move out there and we’d have Thanksgiving dinner right there in hunting camp. And there are still a good number of those camps operating today, especially as you get closer to the Mississippi River.”

“Hunting’s just what we grew up doing,” adds Saxton. “I’ve been doing it since I was a little bitty kid, and I’ll be hunting ’til the day I die.”

While staying at Saxton’s lodge, I met a steady stream of hunters, many of them members of a deer lease who live in nearby Jackson and keep their gear and ATVs at Saxton’s lodge. Driving around, I saw lots of blaze orange dotting the wood lines at ground level and up in hunting stands.

Northerner though I am, I felt like it was home—a hunter’s home.

■■■

“Grab a jacket,” Saxton said to me the third night. “Friend of mine killed him a big buck.”We drove to a lifelong friend of Saxton’s who, late that afternoon, had bagged the biggest buck of his life, a non-typical with antlers that green-scored 199 inches the next day.We stood around the deer in the yellow glow of garage lights, the buck and his huge rack draped over the back of a four-wheeler, while Saxton’s friend relayed his story. The man was experiencing that mild form of hunter’s shock; he’d pause momentarily and try to find the words to tell the next part of the story, still trying to understand how this great event happened to him.

Actually, I knew a big buck had been taken locally before Saxton told me; I’d seen a photo of it on Facebook via my cell phone before I left my hunting blind. Folks like Tim Saxton proudly call themselves “rednecks,” meaning they are politically conservative, love their guns and their hunting, and hold on tight to their religious beliefs. For them, “Southern hospitality” isn’t some catch phrase but the actual, time-honored way you treat people.

Yet, fact is, these are rednecks with iPhones and Facebook accounts who plot hunts using Google Maps, and they’re up on the latest guns, optics and ammunition, too. Some of them have trail cameras wirelessly connected to their laptops, while others hunt hogs using $4,000 night-vision setups.

■■■

Seeing that huge non-typical got me fired up for my own big guy, and I redoubled my efforts. But all I saw were does that night.

My last late-afternoon hunt found me in a ladder stand, sitting along a tree line facing a resting ag field. I watched a doe and two fawns for a half-hour, momma eating green weeds, the fawns running in playful circles with each other.

I figured my hunt was over. My tally stood at four hogs, three of them weighing more than 200 pounds—but no deer. Not terrible by any means, I thought, especially as I’d spent some meaningful time with good friends in a fine part of the country. All in all, I knew I was a lucky guy. But of course I couldn’t help but feel some disappointment, deer-less as I was.

The shooting light was just about gone when I spotted several deer far, far down the tree line to my left. Three of them drifted into the field, while the fourth one began trotting along the edge of the field toward me.

I wasn’t sure what it was—buck or doe—until it was within 150 yards and I saw antlers through my binocular. But the light was playing games: 4-pointer, spiker? Then he stopped and nosed the ground a few seconds. When he lifted his head, I clearly glimpsed through my binocular six points—six that spread out beyond his ears. He wasn’t a giant, but he was legal. In the Delta, a buck has to have either a minimum inside spread of 12 inches or a minimum main-beam length of 15 inches. This guy was 12 inches inside, easy. He kept moving in my direction, and when he got to within 60 yards, one shot of the DRT .308 folded him.

Trophy? Yes, all six points and 140 pounds, my first Mississippi Delta buck.

I felt a part of something, too, something larger and older than myself. Sure, I’d used ARs and some techy gear. Yet this experience was still all about hunting, about spending time in the Delta woods and sloughing over the muddy trails, about laughing and joking and connecting with my new friends. Mine was a very small addition to a rich local history of hunting and camaraderie, but it was mine, never to be forgotten.