The one regret I have about our pastime is sometimes a hunt ends too soon. Don’t get me wrong: I don’t mind it when luck shines and somebody gets to sleep late—especially if it’s me. But after spending months dreaming about elk hunting, it seems like a fella ought to leave elk country with his fill of Western sunrises and sunsets, his nose stuffed with the scent of sage and his ears ringing from bugles by bulls in rut. If he does everything right, and if he’s lucky, he also leaves with the stench of such a bull on his knife, gloves and trousers. The sights and scents and sounds fill his dreams for another year, or maybe more, until he can again find time and money to travel west and hunt the great wapiti.

Today, after many elk hunts and a handful of bulls to show for it—including a whopper—I have but two goals whenever I head west: To “see a big-un” and to get my fill of elk country.

Accomplishing the former isn’t always possible, and I know that, so I am satisfied just to get the opportunity to hunt what I consider North America’s greatest game. Remember, not long ago elk were scarce. Today, their numbers are sufficient in the West to produce opportunities to buy tags across the counter, to hunt units managed for the greatest opportunity for hunter success or to hunt limited-entry areas for fabulous trophies (if one is lucky enough to draw a tag). Elk are even hunted in Pennsylvania, Kentucky, Arkansas and other states east of the Mississippi, where they historically roamed (though opportunities in such places are limited).

Now, how one traverses elk country varies depending on your physical condition, or your guide’s methods; horses or pickups are used, but invariably shoe leather and one’s ability to pick it up and put it down comes into play. Regardless where you go, it’s a rare sight indeed to see a whopper in your scope. We all may have dreams of pack trains plodding into the Rockies, of canvas tents and campfires and giant racks with whale tails strapped to panniers on return trips, but huge elk don’t grow on trees.

The latter goal: That’s up to me. So long as the hunt lasts, I soak in the scenery of elk country. I feel gypped if I don’t get my fill.

Roughly 90,000 elk roam New Mexico, the Land of Enchantment. The U.S. Forest Service manages almost 40 percent of the land there; the Bureau of Land Management runs more than 10 percent; Native American tribes own 13.8 percent; and about 30 percent is privately held. This quilt provides unique opportunity for hunters with a variety of dreams and incomes, because it’s believed that up to 56 percent of the elk in New Mexico use public land. New Mexico Game and Fish manages different game units for different goals. Some units are managed for trophy hunting; they usually have few elk but fabulous opportunities to see a whopper. But many units are managed for hunter success; they hold many elk but not necessarily giant bulls. The management philosophy ensures even do-it-yourselfers have reasonable chances at seeing bulls on national forest lands.

But no matter how you cut it, your best odds usually lie on private land. Land owners know this. In bad years when cattle merely pay the bills, elk hunting can be the difference between breaking even and making a profit. The economic impact to rural communities from private landowners selling bull tags is estimated to be $34 million in New Mexico. Public-land hunters pump even more money into local restaurants, motels, gas marts and meat processors.

Four of us gathered in Grants, N.M., last year to hunt a 12,000-acre parcel of the Mirabal Ranch with Triangle T Outfitters (triangletoutfitters.com). The parcel did lie in a trophy-only unit, and though that suggested we wouldn’t necessarily see many big bulls, the reason we booked the hunt was because the ranch sold only eight tags a year: four to bowhunters and four to rifle hunters. Our party would be the last of the year, and the only rifle hunters. Better yet: Though the historic drought that swept the West last year made headlines across elk country, we were heartened to learn the ranch held lots of water, and all of it was pumping. Outfitter Ed Tibljas informed us before our arrival that elk flocked there. Based on preseason scouting, sightings during archery season and trail-cam pics, he figured the ranch held no less than 46 quality bulls.

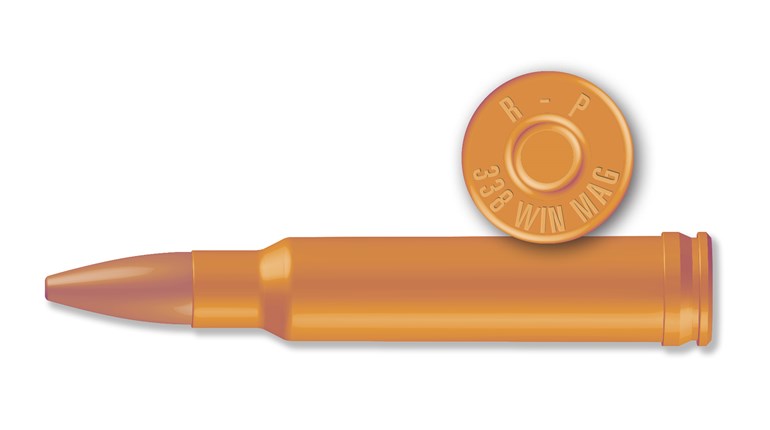

The plan was to wring out the new Remington Model 783, a low-cost bolt-action for which the company has high hopes. I chose Remington’s Premier A-Frame ammo floaded with a Swift dual-core bullet chambered for 7mm Rem. Mag. for good reason: 2012 was the 50th anniversary of the venerable Western cartridge. Besides, why shoot anything but a Remington cartridge in a Remington rifle?

On a Sunday morning I sat with my guide, Wes Medina, in his Ram pickup as we bent ears toward bugles emanating from the darkness surrounding us. Maybe Ed’s proclamation was true.

The only problem with the Mirabal Ranch, if there is one, is its topography. The parcel is awfully flat. It lies at about 8,000 feet, surrounded by hills—but there are none on the parcel that allow hunters to climb to gain a vantage from which to glass. Thus Wes’ strategy is to listen intently for bugles, “move to contact” then set up to cow-call and lure a bull.

As the sun rose we poked and prodded then spotted a bull at the bottom of a break in the pines perhaps 150 yards away.

“There’s a bull,” hissed Wes.

I wasn’t sure whether I could count five points or six on one side, and I definitely couldn’t determine the length of the points. Geez, things were happening quickly: Did I want to shoot a bull within the first 10 minutes of a week-long hunt? Maybe the bull wasn’t bad, but in an instant my decision was made for me when it wheeled into the timber.

We moved some more, and eventually we bumped up against a fence that signaled the edge of the property. There were bulls across the fence—we could hear several of them. I set up the Remington on sticks and hunkered down while Wes settled in yards behind me to call.

Who needs spot-and-stalk? I thought. This feels like turkey hunting. The plan was working. Plenty of bulls answered Wes’ calls. But only a raghorn bull came close enough for me to shoot. I could have hit him with a rock … and then everything shut down.

Half an hour later Wes stood beside me and we compared notes. Besides the elk on the other side of the fence, there had to be plenty on our side that had drifted down-slope to our right and then up the other side into thick timber. We could go after them, of course, since we were the last hunters to ply this land for the season. But we’d likely never get a shot and likely see only white rumps shooing away from us. It was better, we both thought, to give the elk their space. It was only day one. We had an entire week. There was no sense spooking anything. The bulls had bugled their fool heads off this morning for two hours; there was no reason to think the same strategy wouldn’t work again tomorrow, if indeed we didn’t get lucky tonight.

And by nightfall that seemed like a plan, since an evening over a water hole produced nary a thing—not even a bugle.

Yet when we returned to the truck we learned Slaton White had killed a bull. Through the phone I heard Scott Godown, Slaton’s guide, ask Wes for help with the recovery. I didn’t hesitate when Wes asked if I minded a detour before dinner. “Heck, yeah,” I replied. “That’s part of the fun. Let’s go.”

An hour later, as Slaton and I stood in the dark over a fine 6x6 bull pushing 350 B&C, he offered that the animal was his first elk ever.

“Well, then, that’s a dandy to start with,” I said.

In the moonlight I thought of good luck and the bulls and hunters who make it and my thoughts drifted to quick hunts past. Such was the case for at least one of us at the end of day one.

The next morning there was no reason to expect anything but another flurry of bugles. Except it didn’t go like that. We heard a couple bugles at dawn, but nothing like the previous day’s action. Eventually, Wes and I picked one bull to work.

We set up like before—me in front, Wes hunkered somewhere behind me. The bull seemed to come to my guide’s calls like a tom turkey itching for a spring tryst. Wes mewed, the bull bugled. I sat and waited, eyes straining to see the bull first—before it spotted me. After the sixth bugle, which came from perhaps a hundred yards away, I rested my rifle aside a tree trunk. The encounter should have ended a moment later. But it didn’t. Just like the toms of spring, that bull evaporated. I never saw it, never heard it again.

Again, Wes and I stood and scratched our heads. Each day it got extremely hot: Maybe I could get lucky over a water hole during midday. So I set up in a blind, ate my lunch and watched a flock of turkeys water there—and little else. By early evening I was bored stiff, and glad to see Wes’ Ram pull into the clearing.

We’d cover a fence crossing on the property’s edge for the evening. Wes explained how the bulls here would jump the fence. If we spotted one in time, and if it paused, I could get a shot, which seemed like another good plan.

My guide was from Trinidad, Colo., and a big proponent of self-sufficiency. We got along swimmingly, what with complaints about the White House and a populace increasingly dependent on government aid producing plenty of common ground to dissect. His family liked to hunt, and they liked their guns, he said. When he wasn’t guiding hunters he fought forest fires, I learned, which made me realize he led a pretty cool life: Make money and find adventure and camaraderie fighting fires in the spring and summer, and come fall make money and find adventure guiding hunters. In fact, he found time in the spring before fire season roared full-bore to get in some turkey hunting, too. It all sounded like a good way for a young man to pass his time. The more he talked the more it was evident to me he dearly loved his work—all of it.

In the midst of our conversation Wes changed gears.

“Hey, we could sit here until dark—and it’s not a bad plan,” he said. “Or we could pull stakes and beat feet to another water hole—make it there before dark if we hurry. There might be a bull there. We don’t have much time to make that move, but it could work. Your choice, man.”

“Sure,” I replied. “We’ve got all week. We can always come back here tomorrow. Let’s see some country.”

The 8,000 feet of altitude didn’t seem to bother me much until then, when I fell behind Wes in our rush for the pickup. My guide ran ahead, leaving me to my force-march, rifle at sling arms, spare hand swinging to spur me faster toward a rendezvous somewhere ahead. When Wes lurched to a stop I unloaded and climbed in, magazine in hand, barrel out the window, and breathed deeply to slow my heart rate.

Which was a good thing, because what happened next can only be described as great, good luck.

Both of us squealed: “Look at that!”

About 60 yards to our left stood a magnificent 6x6. We were speeding so fast the bull had no chance to disappear. It pranced nervously in circles, as if to say, “Where did you come from?” You know how they say you don’t have to look twice at the big ones? That was this guy. I didn’t know whether he was a 5x5 or a 6x6, and it didn’t matter. I saw long main beams. I saw whale tails—whale tails! I’d never shot a bull with tails.

Wes slammed on the brakes, shut down the engine and hissed, “Shoot that bull.”

He needn’t have bothered. I knew when I exited the truck I would shoot the bull if it stuck around. There was no time to internally debate ethics. I was on private land. There was no blacktop within miles. I’d hate myself if I passed on this bull. I had time only to insert a magazine, load a round and throw up the gun. I took half a breath and began my trigger squeeze as the creature paused before wheeling again.

Blam!

The bull ran as I wracked the bolt. A follow-up would likely hit the tree he was headed for but I had to try. And sure enough, I knew when I swung and squeezed that I’d hit the tree. The bull galloped out of view. My last sight of him was a white rump diving down an embankment a hundred yards away.

The whole encounter took less time than it did to read the words that describe it. I reloaded, put the gun on safe and took a deep breath.

“Did you see that?” I asked Wes.

“Did I see it? Man, that bull was huge. You hit him. You hit him good. I saw him shrug when you shot.”

We walked on shaky legs to the last point we saw the bull, following blood along the way. When we looked over the bank we saw nothing … until we glanced to our right. Piled up amid rocks and pines was the biggest bull elk I have ever shot.

Later that evening we learned John Fink tagged out, too, on a 6x6 with broken tines and tips running a harem of 25 cows. That made three bulls in two days. The sight of my bull and John’s and the rack from Slaton’s bull in the back of Wes’ pickup parked at the bunkhouse was a sight to behold. We called the Ram the “Bone Bus.”

I thought about my good fortune and realized it didn’t pay to try to spin it as anything but dumb luck. I’ve paid my dues in elk country. I’ve gone home empty-handed. I’ve spent weeks hiking up and down steep mountains trying to line up shots. I’ve spent agonizing hours at night going over muffed shots in my mind again and again. I know better than to look a gift horse in the mouth. Wes and I figured my bull taped somewhere between 350 and 360 inches. But I didn’t measure it and don’t plan to do so. I’ve seen enough elk to know what I’m looking at, and besides, regardless what it measures it won’t enter any record book except my own.

It was Columbus Day. Perhaps it’s fitting to remember that when Columbus and his crew set out for the New World in 1492, elk roamed as far east as the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Today elk are beginning to filter back into Virginia, but it will be years before anyone hunts trophies in the Old Dominion. In the meantime, elk hunters get their fill out West. Sometimes it doesn’t take long.