Whoever said busy people get things done was talking about NRA President Jim Porter. I know this after spending time with him in turkey camp in April. Driving to the lodge, I think about how this esteemed Alabama attorney, with a peer rating of 5 out of 5, litigates multiple trial and appellate cases—representing cities, counties, gun manufacturers, public entities and NRA-member gun owners—for his law firm, Porter, Porter & Hassinger in Birmingham. He just returned from the funeral of Otis McDonald, the plaintiff in the landmark 2010 U.S. Supreme Court case McDonald vs. City of Chicago, ending the city’s near-30-year handgun ban. He is actively working with NRA leadership to prepare for the upcoming NRA Annual Meetings & Exhibits in Indianapolis, April 25-27. His son and daughter-in-law just gave him and wife Kathryn their second grandchild. And in his spare time, he is meeting me to hunt up a Merriam’s gobbler, the last of the four subspecies he needs to complete his prestigious grand slam. Clearly this man is efficient. Let the gobbler games begin.

■■■

Technically the games began March 15, the opening day of the Florida season, as Porter kicked off his quest with the Osceola—and my series of “Porter’s Pursuit” blogs tracking his progress on AmericanHunter.org. The Osceola only inhabits Florida, and while I admit it took me two trips to get mine, Porter and his 12-gauge Remington Versamax dropped one that day then headed straight for Alabama and subspecies No. 2—the Eastern. After two days of thunderstorms, Porter bagged his bird as I blogged about how we turkey hunters typically consider the wily Eastern to be the most challenging subspecies of all. Hours later, he was in Texas for subspecies No. 3—the Rio—tumbling it the next day. That’s three birds, one shot each, over five days of hunting. Who gets that? I wondered. Now one bird away from the slam, responsibilities forced Porter to call it quits until April, returning home to address other pressing matters. Not even the NRA president can hunt full-time.

■■■

Looking forward to chronicling the last leg of Porter’s quest in person, I enter New Mexico’s Vermejo Park Ranch (VPR) dining room at 4:30 a.m. on April 15 to meet Porter for the first morning hunt. It’ll be fitting if Porter gets his Merriam’s today—exactly one month since he began his quest on March 15, I think. But with turkey hunting, is Porter’s luck too good to be true? Will No. 4 be as easy?

We meet guide Dave Winebark and pile into his truck—he and Porter in the front and me, my notepad and camera in the back. Heading up the mountain, Winebark stops and calls, we listen. Finally—a gobble. Winebark, Porter and I go set up but never hear another peep. The rest of the day proves uneventful—odd for a place full of gobblers; not odd considering their stereotypical unpredictability.

■■■

Word gets out when the NRA president is on hand. At the lodge we chat with the other hunters before dinner. Porter talks with everyone in the room—drawing them out, making them feel special. He is open to their viewpoints, genuinely interested in what they have to say. And he has something interesting to say in return. But this is our NRA family—who we are, the way we do things—supporting each other and working for the common good. So as Porter would ask, if you’re reading this and you are a gun owner and hunter but not an NRA member, why not?

■■■

At 4:30 a.m. we meet for breakfast. Our guide is ready to go—so is Porter—as they ponder gobbler-ambush plans.

This morning we strike out again. We see birds—just no gobblers. We grab a quick lunch at the lodge. Even there we have no cell service so Porter borrows the front office’s phone to conduct business. Back in the truck, Winebark’s phone at least has intermittent service so Porter makes use of one last opportunity for communication before heading up the mountain.

“…We want to give the governor special recognition for support on our legislation and for helping Remington to move to Alabama,” he says to the person on the other end. “I want to make a presentation at the NRA show’s Board meetings. …”

Seconds later he is on the phone again. Winebark parks the Chevy, gets out and scans the area. Porter is talking with staff, keeping tabs on his caseload. Time is of the essence—and there is so little of it for an attorney with cases in multiple states.

Dave hurries back—a gobbler. I stay behind this time. They return five minutes later after a hen foils the attempt. Porter just looks at me and smiles. “How come you girls are always causing trouble?”

“It’s just a reminder we play by their rules,” says Winebark.

■■■

Later I ask Porter what made him run for an officer position on the NRA Board he has served on since 1989. “I don’t know if I thought about it that much,” he says, in between jarring bumps along our road less traveled. “I just wanted to serve. It’s something I always thought I would do.”

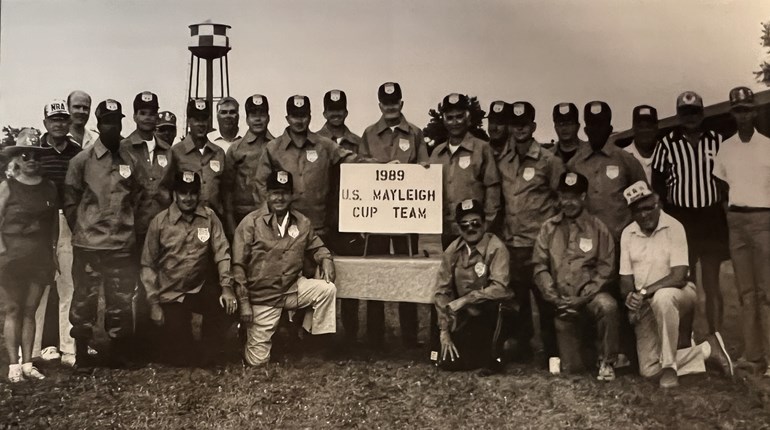

Before that, Porter served on the Board’s Legal Affairs and Nominating committees. The NRA is in Porter’s blood—literally—considering his father, Irvine Porter, served as president from 1959 to 1960. Also a lawyer, the senior Porter founded the family law firm in 1931 and, as an avid target shooter and hunter, introduced his son to outdoor family traditions. As I picture all the 8x10 portraits of NRA past presidents at headquarters in Fairfax, Va., I recall Irvine Porter, in particular, the only one of the group who sidestepped a business suit for shooting attire—fitting considering the many summers father and son spent at Camp Perry as Dad competed in NRA’s annual National Matches. Jim Porter would one day pass along his shooting sports, hunting and wildlife conservation heritage to his own children, son Jay, who is also an attorney, and daughter Katie, who teaches gifted children.

“Dad also loved to bird hunt, and I followed him around like a puppy,” Porter recalls. This led to talk of hunting and his quest for a grand slam. “I have a number of Eastern birds, but I only have Easterns, and thought hunting all four subspecies would resonate with our members,” he adds.

“Dad also loved to bird hunt, and I followed him around like a puppy,” Porter recalls. This led to talk of hunting and his quest for a grand slam. “I have a number of Eastern birds, but I only have Easterns, and thought hunting all four subspecies would resonate with our members,” he adds.

As Porter recounts his first three whirlwind grand-slam adventures, it’s obvious they occurred on good friends’ properties and that those friends, like Porter, are leaders in wildlife conservation (see sidebar). When I ask Porter about his own conservation work, he is uncomfortable talking about himself. For now I acknowledge his commitment to hunting and public access to the outdoors and to his accomplishments as an attorney and a trustee of NRA’s Civil Rights Legal Defense Fund as he continues challenging the courts to undo restrictions on our firearm rights.

“Being a membership organization is different because we serve and work for our members,” he explains, adding, “All we have to sell is service. It tickles me when we’re called a gun lobby because we’re just speaking for the little people. Our strength comes from the bottom up—not the top down. You can’t ever forget it’s the guy paying $35 a year for a membership who is making this organization a success, but we’ve also got to have the big money to do what we do.” This is why Porter worked hard to create The NRA Foundation in 1990 and its essential donor programs. “We’re doing a better job …,” he says, trailing off, likely pondering another to-do list as past president of The NRA Foundation’s Board of Trustees.

■■■

We round the corner, Winebark hits the brakes. Along the dirt road is our mark—a strutter with a hen, and from the looks of things he’s quite hefty, prancing in the open. “Busted—the Santa Fe bird,” Dave says. “Big bird. The guides have tried to ambush him for two years.”

We head to a spot where Winebark gets cell service so Porter can make a call. “I’m hunting in New Mexico—it’s like work,” he says to the person on the other end before launching into details about a lawsuit in New York’s Second Circuit Court on behalf of a firearm manufacturer. Effortlessly, he switches from one role to the other—from hunter and pal to high-profile attorney and even higher-profile NRA president.

Porter ends the call and we drive to a new area. “Somehow we’re missing something,” he says, clearly not talking about the turkeys—as our scouting leaves no stone unturned. “There are 15 to 16 million licensed hunters, yet we’ve only got 5 million members. We need to tell our story better—what we do for hunting and wildlife conservation. We’ll start doing that at the NRA Annual Meetings—at the luncheon on April 25th.”

He is referring to the inaugural NRA Hunters Leadership Forum event next week, the kickoff gathering set to build the strongest possible peer group of leaders to enrich and grow NRA’s leadership for hunters and hunting (see sidebar). Clearly, no other organization works as rigorously and faithfully for gun owners, hunters and shooters, defending our rights, fighting our battles and supporting our programs—and also pays the bill.

■■■

“How many turkeys are killed in Alabama annually?” Winebark asks Porter. “Around 10,000—with a five-bird limit!” he replies, as Alabama boasts more turkeys than any other Southeastern state. Conversation turns to hunting and wildlife conservation as I recall the Alabama Wildlife Federation (AWF) presenting him with the 2013 Conservationist of the Year award for his lifelong contributions to hunting and promoting public access to the outdoors, including serving on the NRA Board’s Hunting and Wildlife Committee from 1994-1996. Porter’s family has owned land in Alabama for 100 years, actively managing it for quality timber, wildlife habitat and hunting—but Porter’s efforts go even deeper. No wonder he was also selected for membership in the International Order of St. Hubertus, an organization of distinguished hunters and conservationists since 1695. Named after Saint Hubert, the patron of hunters, the organization’s motto is “Deum Diligite Animalia Diligentes”— “Honoring God by Honoring His Creatures.”

■■■

Porter is a walking NRA history book. As we chat about the American Firearms and Shooting Foundation, an NRA organization with a self-perpetuating board of NRA past presidents supporting firearm safety, marksmanship training and hunting rights, he highlights NRA leaders of the past—particularly Harlon Carter, who served as NRA president from 1965 to 1967, headed the newly created NRA-ILA in 1975 then served as NRA EVP from 1977 to 1985. Porter recalls Carter fondly, having grown up around him and his father’s other NRA colleagues, including George Whittington for whom the NRA Whittington Center in Raton, N.M., is named. Porter recounts the ground-breaking of the NRA building at 1600 Rhode Island Ave. in Washington, D.C., in the 1950s. I share a historical tidbit of my own, recalling the American Rifleman (AR) magazines I’d just come across from 1929 and the fact every cover showcased a hunting scene—from moose to African elephant. American Hunter wasn’t launched until 1973, so AR accomplished double duty in highlighting NRA’s defense and promotion of hunters and hunting.

■■■

We stop so I can photograph a herd of bison. It starts snowing. Winebark spots turkeys in a field 100 yards past the tree line—three strutters. Porter and I set up. Winebark pops up a decoy and calls. A gobbler answers once, twice, three times—he’s coming. I see him, Winebark sees him, Porter does not—until he is out of range. Aware something’s off, the bird splits. Man, those spindly legs can go. No pressure, Winebark. Just find us another one.

“Well, that’s hunting,” Porter says, back in the truck. He is quiet, likely mulling over the calls he needs to make in a land with spotty cell service and the fact his turkey time is running short. This is one of the most important hunts of Porter’s life with a prestigious grand slam in reach, yet I never feel he has to get a bird. No urgency—just patiently waiting—and hoping. We’ve all been there.

Porter realizes tomorrow is the 17th. He needs to get home in between his own work and NRA business. “I didn’t think a Merriam’s would be this hard,” he says. “I thought they were one of the easier subspecies to hunt.”

■■■

By now I’ve earned the nickname Sparky as leaning out the truck window to photograph critters creates such electricity that I shock my truckmates every time I hand them something from the back seat. As conversation switches to NRA-ILA’s Conservation, Wildlife and Natural Resources department and NRA’s history of hunting and conservation accomplishments—from passing the SHARE Act in the House to keeping federal lands open to hunters and safeguarding Farm Bill programs—Porter again wonders why every hunter is not an NRA member.

■■■

Still snowing, it’s 5 a.m. on day three—Porter’s last day to hunt. We head to where Winebark has birds on the roost. Winebark calls and two gobblers answer. Turkeys fly down literally on top of us, but the hens walk away with toms in tow.The snow stops and turkeys are everywhere after hunkering down since yesterday, seeking breakfast bugs—and girlfriends. We compete with hens for another gobbler. The hens win.

Finally, temps are rising. The snow starts melting. Then Winebark’s Chevy stalls—and stops. We’re stuck. The more Winebark tries to break free, the deeper we sink—wheels spinning, mud flinging … in the middle of nowhere … on a mountain … no cell service … on the edge of a drop-off.

Winebark gets on the radio. We step out of the truck for safety to await help from camp.

The turkey clock ticks.

■■■

Two hours later we’re cruising for turkeys. It’s 12:15 p.m. Fortunately the only sure thing about luck is that it will change.

We spot hens and a strutting tom at the bottom of the hill along a creek. The gobbler is so caught up in his performance he has no clue we’re easing out of the truck at 150 yards.

“Let’s try spot-and-stalk,” Winebark says. This may be it, one way or the other, I think, knowing to stay behind in this particular setting. “We’ll stay silent and let the birds do what they’re going to do,” Winebark whispers. As they inch along, I listen—and pray—for a slammin’ success.

Boom! Porter’s shotgun fires. Gobbler down! I start rushing to get in on the action. Boom! Porter fires again. This can go either way.

From a clearing atop the hill, I see Porter and Winebark below along the creek. There is no bird.

“He’s in the creek!” Porter exclaims, laughing alongside Winebark. Seems the gobbler was still moving after the first shot. “He wasn’t taking any chances,” Winebark explains. “The second shot sent him into the creek!”

We take a precious moment to celebrate Porter’s Merriam’s and one heck of a hard-earned grand slam. As he and Winebark pull out the waterlogged turkey, I see how deep the creek is. “He wasn’t going anywhere,” says Porter. “Hurry, let’s weigh it before it dries out!”

NRA President Jim Porter was meant to get this bird—one way or another—as I tried to dry it for photos. I’d never seen such a bedraggled specimen of a gobbler as I smiled, wondering if Porter was ever as proud of a turkey.

■■■

We’re at the airport. It’s 5:30 a.m. I’m whipped, sitting at the gate. Porter is busy making friends with Jim Johnson, wildlife management officer with the Georgia Department of Conservation, and two female Junior Olympic shooters. Ever pleasant and sincere, this classic Southern gentleman is interested in their opinions and activities. I think of how he has one year to go in his presidency as he will serve two one-year terms like most presidents before him—except Charlton Heston, who was voted back in for five consecutive terms. Porter knew Heston well, saying, “Well, who wouldn’t want Moses speaking for us?”

As I consider next year’s Annual Meeting when Porter steps down, I know his goal is the same as NRA EVP Wayne LaPierre’s: to leave the NRA better than he found it. As for Porter’s legacy, hunting and wildlife conservation will shine brightly. What he and the NRA do for hunters and gun owners is unparalleled. Thank you, President Porter, for dedicating your time and energy for the good of the group. Like Porter, if we all do our part, the unified voice of hunters and NRA members surely will keep freedom alive.

Trackin’ Turkeys

Jim Porter’s time line covers four birds in four states in eight days. Check out the “Porter’s Pursuit” blog here.

■ The Osceola: The Gilchrist Club, Trenton, Fla., 3/15/14

Porter hunts the Gilchrist Club at the invitation of club and NRA Life member William (Larry) Shores, who says its 27,000 acres of managed timber and habitat are loaded with Osceolas. The fact Shores is passionate about the NRA and conservation—and has hunted six continents—is enough to convince Porter. An added bonus: reconnecting with club manager and former NRA employee Bob Edwards. Porter hunts alongside club guide and wildlife manager Randy Ransom and Ransom’s son, Randy Jr., dropping his gobbler at 20 feet with one shot. The 3-year-old 20-pounder has 11/2‑inch spurs and a 7-inch beard. NRA Publications photographer Forrest MacCormack and “NRA All Access” television cameras capture the moment.

■ The Eastern: Palamar, near McIntosh, Ala., 3/18/14

When downpours shut down hunting, the next best thing is being in hunting camp as Porter holes up at Palamar, the 2,500-acre historic hunting grounds and country home of Riley and Tammy Smith. A former Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources commissioner and CEO of the Tensaw Land & Timber Company, Smith serves as Vice Chair of the NRA Board’s Hunting, Wildlife and Conservation Committee. Palamar is recognized as part of the state’s TREASURE (Timber, Recreation, Environment, Aesthetics for a Sustained Usable Resource) Forest program, attaining TREASURE Forest certification in 2002. Guide Albert “Chubby” Parnell leads Porter to a 4-year-old, 18-pounder sporting 11/4 -inch spurs and a 9-inch beard.

■ The Rio Grande: near Pearsall, Texas, 3/19/14

Granger MacDonald—head of the MacDonald Companies, fellow member of the International Order of St. Hubertus and newest member of NRA’s Hunting, Wildlife and Conservation Committee—wants to help Porter earn his slam and offers Porter use of his and partner Kris Perryman’s 3,000-acre ranch. Porter calls in a 20-pound, double-bearded tom with 8- and 10-inch beards and 1.25-inch spurs.

■ The Merriam’s: Vermejo Park Ranch, Raton, N.M., 4/17/14

Porter hunts the 590,823-acre Vermejo Park Ranch, renowned for its forestry and wildlife conservation practices and outdoor opportunities. Guide Dave Winebark leads Porter to a 4-year-old, 18-pounder with a 71/2‑inch-inch beard and ¾-inch spurs. Porter finds the snowy spring-time scene symbolic of the diversity hunters experience when they hunt the four turkey subspecies comprising the grand slam. A quest that began in the Sunshine State ends in the Land of Enchantment at 8,000 feet amid snow-capped mountains.