Think of Arkansas duck hunting and imagine standing in knee-deep water among flooded oak trees with a flock of mallards circling overhead. Your heart is in your throat as you anticipate the moment when they’ll lock up to drop into the “hole,”—greenheads side-slipping through flooded timber provide one of waterfowling’s greatest thrills.

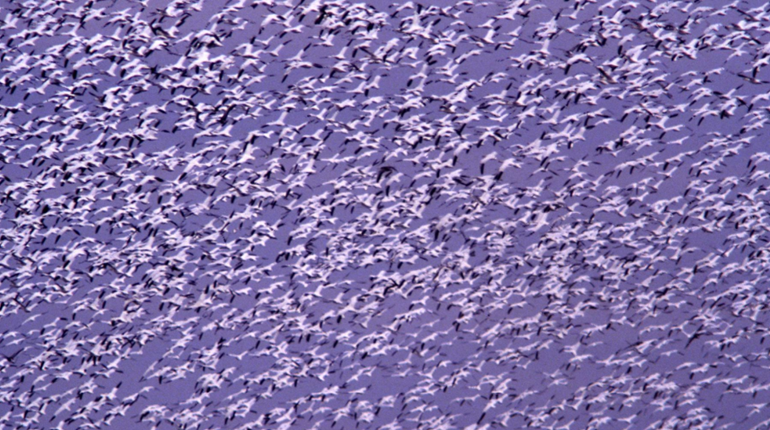

Considered a waterfowler’s Mecca, Arkansas’ Grand Prairie region has a reputation that’s pure duck. Hunting the flooded hardwood bottoms that dissect the Grand Prairie’s vast farmland is considered the champagne of duck hunting. But the “meat and potatoes” of the area is the flooded rice and bean fields—a major food source for thousands of migrating ducks and geese and the reason why so many are drawn to the Grand Prairie from every corner of the massive Mississippi flyway.

I’ve enjoyed some especially memorable days duck hunting flooded timber with Frank Lyon of Little Rock at Wingmead, his 14,000-acre farm near Stuttgart, Ark. Edgar Monsanto Queeny, head of the Monsanto Chemical Corporation, St. Louis, Mo., bought Wingmead’s original acreage in 1938. Queeny, guided by the management programs of that day, constructed a system of levees that impounded Peckerwood, a 4,000-acre lake. This enabled him to control the seasonal green timber flooding on Wingmead and to establish a significant rest area for wintering waterfowl

In 1946 Ducks Unlimited published Queeny's book, called Prairie Wings, which features ducks at Wingmead. Even by today's standards the book, which is enhanced by the comment and sketches of Richard Bishop, is unequaled as a study of ducks in flight.

Frank bought Wingmead in 1976 and began implementing a wildlife management program that incorporates a versatile rice and bean farming operation with the seasonal needs of the largest concentration of wintering mallards in the country. Frank’s innovative wildlife programs play a crucial role by providing food, habitat and protection for all the species that occur there.

“Peckerwood Lake, for example, is an important ‘rest area’ for the wintering ducks and geese,” Frank explains. “Most of the ducks that are hunted throughout this region, not just Wingmead, use the lake at one time or another during their winter stay. The lake, which is open to public fishing for most of the year, is closed during the winter to avoid disturbing the ducks.”

On a recent crisp November morning the sky was busy with ducks returning from feeding forays in nearby rice fields. Their chests bulged with grain as they circled the timber in silhouetted formations searching for the company of other ducks on the water. At the edge of a hole in the timber stood our group, which included Wingmead’s Maurice Eason, and Tim Doepel, both experienced duck callers.

Calling mallards is the essence of green timber shooting. In the hands of an expert, a duck call becomes an instrument of duck music coaxing and cajoling greenheads out of the heavens. When mallards drop through the trees, sometimes fanning you with their wingtips before they land, it will literally take your breath away.

Leaning against tree trunks to obscure our outlines, we stared skyward at the aerial spectacle. While mallards sailed overhead we kicked the water to give movement to the decoy spread. On the fourth pass rapid chatter feeding calls were offered, causing the lead drake to drop suddenly through the branches in a vertical descent to the water. The flock followed and within seconds over two dozen mallards swam among the decoys—some close enough to scoop up with a net.

Official shooting time was still minutes away, so I only watched as one drake swam by only a few feet away. When he became aware of us he beat a retreat up through the trees, taking the flock with him. More ducks dropped in with wings locked and feet dangling, some of them splashing down like bricks.

Mesmerized by the sight, no one thought to raise a shotgun, but when Maurice announced it was time to shoot, it took no further inducement to load up.

“Get ready,” Maurice whispered as he began to call to a flock of greenheads. “Kick the water,” he whispered between calls. “They’re looking.”

As a dozen ducks fell below the treetops Maurice commanded, “Take ’em!” The first shot echoed through the woods, immediately followed by the boom of the other guns. At the sound of the shots four drakes folded and fell among the decoys. The flock reversed direction, winging upwards through the trees. Second shots connected with two more drakes and they crumpled simultaneously as if colliding with an invisible ceiling. The shots resonated through the woods like rolling thunder—then all was quiet.

Tim and I waded out to pick up the six ducks. Admiring the brilliant green-headed, curly tailed drake mallards, we held them up for the others to see. We put the ducks on a dog platform next to the tree where I stood and then looked skyward for more ducks.

“Teal!” Maurice hissed. “Get ready!” A flock of teal zipped through the timber, passing over our decoys before anyone could think of shooting. Maurice called after them with rapid quacks, while the rest of us remained absolutely still.

In timber, teal will typically whip past the decoys, disappear and then slip back in when you least expect them. When you’re convinced they’ve left the woods, they’re suddenly sliding into the decoys. Guessing from which direction they’ll appear usually makes their sudden reappearance a surprise.

Frank caught the flock’s movement out of the corner of his eye and signaled us just before the teal sailed over the decoys. At the sound of the shots they kicked on the after-burners and virtually skyrocketed over our heads to leave the woods. Few shots missed, though, and when Tim and I waded among the decoys, we retrieved eight little ducks.

Engaging two more flocks provided our mallard limits of four greenheads each. The teal we had taken earlier completed our combined limit of six ducks apiece. We put away our guns, but continued to enjoy the air show of ducks coming to the call through leafless oak woods.

It seemed to me that surely a few ducks would come in without the enticement of a call, so when I asked Maurice about it, he smiled, put away his call and said, “Watch.” He already knew the answer, and it didn’t take long before I too was enlightened.

Maurice, whose blue-gray eyes never stop searching for ducks, watched the sky with amusement. Within minutes the flocks circling overhead moved elsewhere. Not a duck came near us, although we could still see ducks in the distance. Maurice explained that a duck call in the timber is much more important than the decoys. “Ducks respond more to sound than sight in the timber,” he explained.

“To show you what I mean I’ll start calling again. When I get a flock working, on the third or fourth pass I'll bring ’em in. Then I’ll give ’em an alarm call before they can land. When they climb out of the hole I’ll call at a certain point to bring them right back in.” Maurice explained.

Pretty tall order, I thought, but Maurice not only did what he said he would, but explained each call as he did it. Each call was different and he described how the ducks would react to it.

“This type of calling will never win the Contest,” Maurice said, referring to Stuttgart’s annual World Championship Duck Calling Contest. “I've judged the World Championship, and contest calling tends to be somewhat exaggerated for the judge’s sake. In the woods you have to talk to the ducks, and it takes knowing what they want to hear. Contest winners who blow technically correct calls might have a slow day in the woods if they don’t adapt to what the ducks are doing. I rarely call unless I can see the ducks I’m calling.”

After a few more minutes Frank suggested we let the ducks have the woods. Tearing ourselves away from the aerial exhibition, we waded to the hidden johnboat and climbed aboard. Weaving through trees, we flushed mallards all the way back to the boat landing.

Wingmead’s old log books from the late 1930s record a passage written by Nash Buckingham, who commented that after a wonderful shoot in ‘Greenwood’ they were back at the main house with limits of ducks before 8 o’clock. I looked at my watch and it was not yet 8 o’clock. Mallards circling over Arkansas’ legendary flooded timber are still providing the timeless thrills and excitement enjoyed by Queeny, Buckingham and countless other hunters from bygone eras.