lkhorn City, Ky., just across the southwestern border of Virginia, is actually a very small town despite its name. Surrounded by mountains and bisected by a river, this place has a history older than the town itself. This is where, 250 years ago, the man who would become America’s greatest frontiersman first set foot in the land that extended the American frontier beyond the Appalachian Mountains. The man was Daniel Boone. The year was 1767.

Boone and two companions had come from North Carolina. Hunters and trappers, they were looking for bountiful game and, if possible, a way to reach the promised land of Kentucky. Exploring southwestern Virginia and crossing the mountains, Boone followed the Russell Fork (tributary of the Big Sandy River) through the scenic Breaks Canyon. That took him via what is now Elkhorn City. He wintered near what is now Prestonsburg, Ky., before returning home.

He had heard of the American buffalo—the bison—but never seen one. In the 1760s, thousands of bison still roamed Kentucky and the surrounding region. On this trip he finally saw them and hunted them. He relished their meat.

Nevertheless, Boone did not think he reached Kentucky on this trip. So, he organized a larger expedition two years later. That 1769 expedition took a different route, crossing the Appalachian Mountains at the Cumberland Gap. That trek took him into the heart of Kentucky. So fascinated was he that he did not return home for two years; his absence caused much worry among his wife and children. This and his subsequent expeditions made the Cumberland Gap the most famous mountain pass in America, and thousands of Americans seeking fertile land and fine game followed his footsteps and moved into Kentucky and beyond, the region historians call the Trans-Appalachian West.

Born (in 1734) and raised in Pennsylvania, Boone began hunting when very young. Later, he frequently engaged in what was called a “long hunt,” where the hunter stayed in the woods for weeks or months at a time until he gathered sufficient meat for sustenance and skins for sale. That activity, combined with a wanderlust that lasted all his life, took him far and wide. His travels—by foot, on horseback and by boat—spanned a vast region that today includes Michigan in the north and stretches as far south as Alabama and Florida, then across the Mississippi River to Missouri and beyond.

In 1810, at the age of 76, then living in Missouri, he and a group of younger men explored the Missouri River and traveled as far west as the confluence of the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers, near today’s North Dakota-Montana border. It is such exploits that enhanced his legend in his own lifetime. In contrast, many men of his time were bedridden by their 60s, and that’s assuming they reached their 60s in the first place, for the life expectancy was only about 50 years.

But of course it was Kentucky that made Boone famous; in particular, his founding and defense of the fortified village named after him, Boonesborough. However, Boone was not the first American in Kentucky; in fact, he heard about Kentucky from others who had been there. But he was the most respected enthusiast for Kentucky. As an accomplished woodsman, he exuded a confidence that inspired his contemporaries to follow him. He was also honest and forthright; people did not wonder if they were hitching their wagon to a charlatan.

Some of his most daring exploits occurred during his time at Boonesborough. In 1776, his teenage daughter and two other girls were kidnapped by Shawnee Indians while the girls were canoeing. After a three-day pursuit—where his uncanny ability to anticipate the Indians’ moves dazzled the men who accompanied him—Boone and his men finally rescued the girls, after shooting two kidnappers. Boone was widely celebrated for this feat. (It even inspired James Fenimore Cooper’s classic 1826 novel, The Last of the Mohicans.)

Two years later, in 1778, Boone himself was taken by Shawnees. He spent four months in captivity. One afternoon, while the Indians were hunting turkeys, he jumped on a horse and galloped away as fast as possible. Indian squaws screamed to alert their men, who stopped the turkey hunt and gave pursuit.

Boone managed to gain a wide lead, riding all night into midmorning, but then his horse gave out. Undeterred, he took to his feet, using his woodsman’s savvy to hide his trail—such as walking on fallen trees so his footprints would not be traceable, and running in fast-flowing streams (whereas stepping into stagnant or slow water would leave a muddy cloud visible to a pursuer). In total, he traversed an astonishing 160 miles in four days, finally arriving at Boonesborough to a stunned audience.

But not everyone welcomed him back with open arms. During his captivity, Boone had shown an eagerness to adopt Shawnee customs; it was a stratagem for gaining their trust so one day he could find the opening to escape; besides, had he been a hothead he would have been scalped on the spot. However, when some people in Boonesborough heard about his Shawnee assimilation, they thought he was now siding with Indians, who were allied with the British. We must remember this was in the middle of the Revolutionary War (1775-1781). So, Boone, who was a leader of the militia, was court-martialed on charges of treason. He was acquitted, but this became the most humiliating episode in his life.

At a time when many of his fellow frontiersmen regularly lost their lives in encounters with hostile Indians in the woods, Boone survived every such encounter—thanks to his ability to defuse tense situations. Thus, if handing over his expensive guns and a hundred hard-earned deerskins was what it took to pacify Indian ambushers, then he did just that instead of chancing a fight that might end with his scalp in Indian hands. Simply put, Daniel Boone knew when to hold and when to fold.

As a militia leader, his command of men and materiel during a 10-day battle with Indians in 1778, known as the Siege of Boonesborough, resulted in the Indians walking away in defeat. Despite the terrifying fight, several amusing incidents occurred. During one particular incident, an Indian warrior annoyed the besieged Americans by repeatedly climbing a tree, exposing his posterior and tauntingly patting it—the Indian gesture for “kiss my #$$.” Several Boonesborough men fired at him but missed. Finally, one marksman, perhaps aiming at the taunter’s asset where the sun didn’t shine, carefully squeezed the trigger. The Indian tumbled out of the tree and died. Some reports said this marksman was Boone himself, but he never asserted it.

That incident became part of Boonesborough’s legendary history, and Boone biographers continue to describe that shot as having a range from 200 to 400-plus yards. Those distances range from unrealistic to preposterous. Obviously the Indian was close enough that his gesture was noticed. (After all, a striptease is not effective unless it is clearly seen.) Yet he was also far enough away to escape the shots from most shooters, who were probably using muskets, the common firearm at that time, with accuracy at 100 yards that was anyone’s guess. The marksman apparently used a rifle, a far more accurate means. Therefore, considering all factors, the range was probably 150 yards at most.

A commercial hunter and trapper, Boone often took 200 to 500 deer in a season, selling the skins for a profit. Deer skins were in demand for clothing. One morning, hunting in eastern Kentucky, he killed 11 bears before noon. Bear meat was savored by many Americans, and its fat was used as oil. In trapping, taking 100 to 200 beaver skins a season was not unusual for him. He also dug up and sold ginseng roots, which American traders shipped to China.

In his time, game was plentiful, and we should view Boone’s actions in that context, not by our modern hunting ethics. However, Indians frowned on white hunters (including Boone) who often took only the skin and let the animal’s carcass rot, and such resentment often led to confrontations. Nevertheless, Boone understood the indispensability of game as a food source even for white settlers. In 1775, at the founding of Boonesborough, he enacted restrictions against indiscriminate hunting. It was probably the first conservationist action in Trans-Appalachian history.

Boone hunted into his early 80s, camping out with his grandchildren and telling them old hunting stories. In his last years his arthritis worsened, severely limiting his hunts. He died in 1820, a month before his 86th birthday.

After his death, fact and fiction were freely mingled by sensationalists, creating all sorts of myths, including one that persists to this day: coonskin hats. Boone despised them; he wore beaver hats instead.

We can be thankful the real details of Daniel Boone’s life were documented by a historian named Lyman Draper, who, two decades after the frontiersman’s death realized Boone’s impact on the Trans-Appalachian West and began interviewing the surviving Boone family members and associates. He kept hundreds of pages of meticulous notes, which have been the foundation for the reliable biographies of Boone published in the last 100 years or so.

Boone said that a man needs only three things to be happy: a good gun, a good horse and a good wife. He evidently had all three.

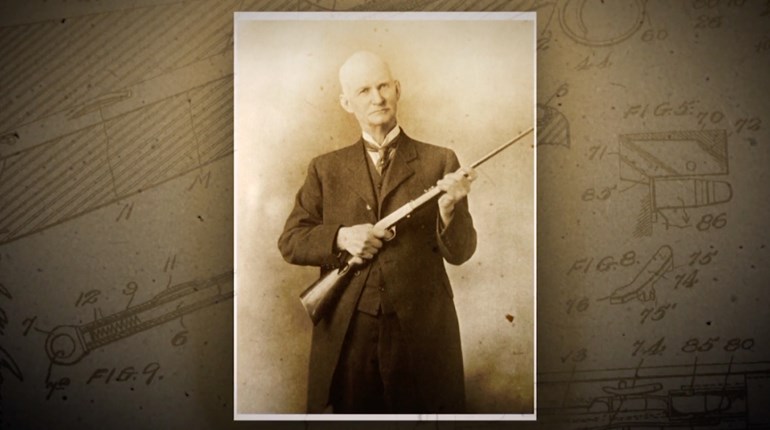

But one of those three things is not a happy cause for many Boone aficionados—his guns, specifically the disappearance thereof. Apparently none of his guns have survived. Several museums have proudly displayed guns purportedly belonging to Boone, only to find that their provenance was murky at best. So many Boone artifacts have been fakes that we might as well say that fakery is an authentic attribute of Boone artifacts.

Nevertheless, he apparently had a favorite gun that he nicknamed the “Tick Licker”—a gun so accurate, the story goes, he facetiously said it could pick off a tick on a bear’s snout.

It was most probably a Pennsylvania long rifle. Lyman Draper said it fired a 1-ounce ball. If so, then it was a 16-gauge gun. (Recall that gauge comes from the number of equally sized balls made from a pound of lead so that each ball fits snugly in the barrel.) A 1-ounce lead ball has a diameter of .66 inch, so in modern terms that would mean a .66 caliber. But in Boone’s time, they still used balls in rifles, not the conical bullets we know today.

However, since Draper was not a rifleman, the Boone associates he interviewed may have generalized the ball weight so he could understand. Therefore, it is also possible the “Tick Licker” was slightly smaller or larger than 16-gauge.

In some ways, Boone was an improbable trailblazer. He was a man of few words, and soft-spoken. Physically, he was not very big. Though robustly built with broad shoulders and muscular limbs, he stood only 5 feet 8 inches tall and weighed about 175 pounds. Yet it is a testament to his character that, two centuries after his death, he still personifies the quintessential American frontier hero. No one else comes even close.

Perhaps one way of describing Boone’s impact on America is to point out his role in the birth of one of America’s greatest presidents. One of the men who listened to Boone was a Virginia farmer, who sold his farm and took his wife and children to Kentucky. The children grew up, and one of them was married in Kentucky and fathered a son in Kentucky. That son was Abraham Lincoln. The rest is history.