Bouncing along two dusty ruts that serve as a road a few miles south of the United States border, Matt Woodward can’t stop talking about maps as he drives through the late afternoon sun. Just days before he confirmed that a Mexican governmental agency had recently published updated topos for the area of Sonora where he hunts, and he’s anxious to get a look at them. Owner of Borderland Adventures, Matt has spent years learning this area—rugged ranchland he leases from a judge in a distant city—by trial and error; to his previous knowledge, reliable maps simply didn’t exist. There are still parts of the ranch he has yet to fully explore. Matt’s guides have to rely on his descriptions of landforms and their own experiences to navigate the rocky hills. Maps will put everyone on the same page, literally, and open more opportunities for the Borderland crew to find Coues deer.

I recognize his excitement and consider that if we were hunting just 10 miles north, we’d take having good maps for granted. Like clean water and sturdy shelter, their availability would be assumed. We’d expect them to appear in an instant on our phones. The contrast is not lost on me. Things changed suddenly when we crossed the border, and that isn’t a bad thing—at least from the perspective of a hunter. Matt doesn’t have the maps yet, and even though he’s already hunted this piece of desert for several seasons, it still seems like we’re entering uncharted territory. It is easy to think of this place as being largely devoid of man’s presence and influence. I quickly learn, however, such musings are not in step with reality.

“Let’s stop here for a minute,” Matt says as he pulls the truck beside a 10-foot cliff that rises along the sandy roadbed. We are several miles outside El Sásabe, the Sonora border town where we entered Mexico. “You’ll want to see this.”

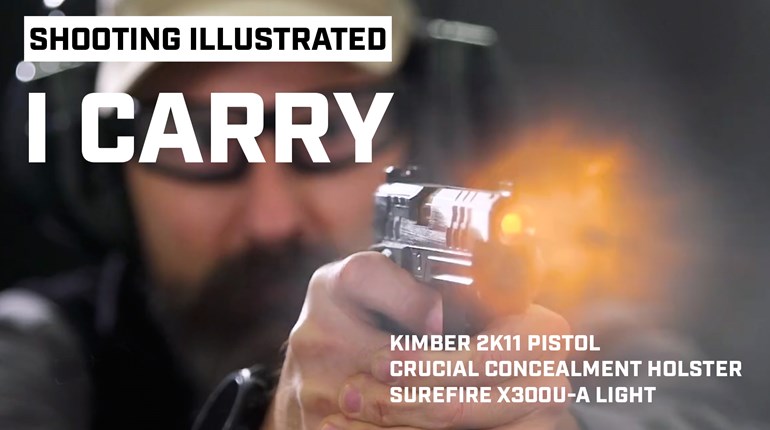

Rachel Vandevoort, my hunting partner from Kimber, and I approach the cliff with growing curiosity. Excavated into its face at shoulder height is an arched hole about 3 feet wide, reinforced with adobe and lined with sheet metal. Elaborate figurines and brightly painted votives bearing the names of saints and other religious entities fill the little cavern.

“They come here to pray before they cross the border,” says Matt. “It’s been this way for years.” I notice a dark, greasy stain that runs from the lip of the miniature grotto to the bottom of the cliff. It is melted wax from probably hundreds of candles. Shattered votives line the sides of the road for yards in each direction. Innumerable footprints pock the sand. The two-track is a highway for human smuggling, and we are standing in the middle of it.

“How many border crossers do you run into when you’re hunting?” I ask. “Oh, we normally see one or two groups a week with six or eight people in a group,” Matt replies. “But lately we’ve been seeing more. I think all this talk about building a border wall has them worried they’re going to miss their chance.”

It is early December 2016. We are all familiar with President-Elect Donald Trump’s plan for increased security along the border. In the months leading up to our hunt for Coues deer, though, I don’t think any of us foresaw the impact it could have on our trip.

Places to Hide

At more than 69,000 square miles, the Mexican state of Sonora is roughly the size of Missouri, but it has less than half the population. It’s almost all desert and grassland, with rock-studded mountains reaching more than 8,000 feet above the plains and rolling hills. Most of Sonora’s residents live in a handful of cities, and the areas between them are remote and nearly roadless. These are the places where Matt and his guides—a tight group consisting mainly of boyhood and college hunting buddies—spend a couple months each winter looking for Coues deer.

A tough little subspecies of whitetail, Coues deer thrive among the spikes and spines that cover Sonora. They are named after 19th century naturalist Elliot Coues, who ironically never collected a specimen of one but instead concentrated on identifying birds. (He pronounced his name “cows,” but most people refer to the deer as “coos.” According to Matt, “Hunters look at you funny when you call deer ‘cows.’”)

Likely due to the dry, hot climate where they live, Coues deer are quite a bit smaller than the standard-grade woodlot whitetail. A good buck weighs about 100 pounds. Antlers are proportional but can carry a surprising amount of mass on older bucks. An 8- or 10-point “teener”—a buck with a Boone & Crockett score of 113-119 inches—is the class of trophy the Borderland guides seek in Sonora. A Coues buck of that size, by the way, will make the All-Time minimum Boone & Crockett requires for entry in its Records of North American Big Game. Finding one is the challenge that calls Matt and his crew across the border every year.

Born in Arizona, Matt has hunted the Southwest since he was a kid. After a stint at Penn State pursuing a degree in turf-grass management (“I thought I wanted to run a golf course … ”), he became a guide and started Borderland Adventures. His decades of experience tell him where and when to look for big bucks, but they still don’t come easy. Coues deer are notoriously elusive.

“I’ll be watching a buck through the glass and glance away just for a second,” Matt says, “and he’ll disappear. It happens all the time. No matter how hard I try, I won’t find that buck again. It’s like he knew he was being watched from a mile away. These deer have a super high sense of danger.”

Although Matt can sometimes pattern bucks drawn to food and water sources, his main strategy is looking over as much ground as daylight allows. He glasses nonstop, meticulously picking apart the terrain with a gigantic 32X binocular braced on a tripod. But even with a bino three times as powerful as the standard big-game setup, the broken Sonoran landscape keeps some of its secrets hidden. There are too many ridges with too many shady draws that hold too much brush and cactus to cover, even with a team of guides eager to show up the boss. And all it takes is a chair-sized clump of ocotillo to hide a bedded Coues buck. Spotting one in this country is like trying to find a needle in the proverbial haystack, but only if the needle is the same color as the hay.

We have a daunting task ahead of us for the week, but even though the setting is the perfect place to sing the praises of superior optics, Leupold’s Shane Meisel and I spend the first night around the fire talking about border crossers. It’s no wonder the “coyotes,” the nefarious guides paid through exchanges that often involve things other than currency to lead groups to the border, run their routes through this area. Much like the deer, they have the benefit of innumerable places to hide. Plus, with this being a working cattle ranch, there’s water in the cattle tanks. We saw several discarded water jugs—painted black for camouflage and to discourage the further growth of bacteria—not far from the bunkhouse where we now sit.

Shane notes that Matt and the other guys seem nonchalant about the activity. We figure they just must be used to it. Besides, we reason, the travelers aren’t really doing anything wrong since they’re still in Mexico, except for perhaps trespassing. Then again, neither of us knows the laws pertaining to private property in Sonora; maybe it’s no problem at all to walk across someone else’s ranch. It seems like a live and let live situation, although there’s a sad pause in the conversation when we stop to think about the abuse the coyotes commit against the women in the groups.

We don’t feel in danger, and in fact the roaring mesquite fire makes the atmosphere downright comfortable. Still, dark thoughts swirl through our minds like the smoke that flows into the room instead of up the chimney. Before we turn in for the night, we load our rifles. When a couple dogs start barking out back a few hours later, we’re wide awake until they calm down.

In Plain Sight

The crisp air and bright rays of the early morning sun clear my head and casts a cheerful light on camp. This is a neat place. The ranch house is rustic in a real sense. It looks like it belongs in the early 1900s and hasn’t been updated since then—save for the conveniences of indoor plumbing and electricity via generator. Everything else is authentic, including the wood-fired cookstove where bacon, eggs, refried beans and tortillas are waiting. The frijoles refritos don’t come from a can here. The cook sorts, washes, simmers, smashes and mixes the pintos with a good measure of lard to whip up a batch of beans that’s as smooth as cream cheese.

Per Matt’s campaign to cover as much ground as possible, our group splits up after breakfast. Shane and Mike Schoby, a senior staffer from another publishing group to whom I’ve given a serious case of beard envy, head out with guide Steve Doyle. Anthony Licata, who works in a New York skyscraper high above Park Avenue and therefore can afford beard implants, goes with Mario Guisto. Rachel and I get Matt.

It’s already getting hot by the time we climb a hill to settle in for a glassing session. We concentrate on scouring the shade, as Matt tells us the bucks will be heading for their beds. Later in the month, when temperatures cool and the rut begins, bucks will be on their feet all day. Luck favors the hunter during that time; right now, we’ll have to rely on our skill behind glass. First Matt spots a couple does, and then Rachel sees one. I find nothing until Matt directs me to another doe with a fawn at the bottom of the hill on which we’re sitting. Although the pair is close for Coues deer, about 250 yards away, it still takes me long seconds to pick them out from the vegetation. A flash of white from the fawn’s tail gives them away. Otherwise, I might still be looking for them. Their gray-tan coats blend in perfectly with the soft, broken shadows cast by the brush.

We spend a couple hours atop the hill but find no more deer, and Matt suggests we take a drive and glass from the truck. Between vantages, we encounter a group of travelers on their way to the border. They’re dressed in street clothes. Some have packs, others have nothing but what they’re wearing. They walk with their heads down, avoiding eye contact. Some step off the ranch road, preferring to pass with the brush between us. It’s clear they want no interaction, and I feel awkward watching them.

“Just another day in Sonora,” Matt says with a shrug. “We leave them alone, and they never bother us. Most of them are scared of getting lost. They don’t know this country; they’re just following the coyote.”

He tells us the group will probably stage at a large water tank down the road from the ranch house. They’ll drink and rest during the heat of the day, waiting until night to try to cross the border. And the coyote will likely take whatever he wants from them before turning them loose.

When we meet up with the rest of the guys for lunch, they share news of similar sightings. But while driving back to camp together, they also ran into something else, something more troubling. A gang of young men, dressed in military camouflage and haphazardly armed with rifles in various states of condition, had waved the hunters over to the side of the road. Judging by the gang’s appearance and firearms, Steve and Mario say they were likely guardsmen for a drug cartel, positioned to keep watch over a “mule” traveling with product.

“They asked us for marijuana, water and deer meat,” says Steve. “We gave them a couple bottles of water.”

“They know we’re in here hunting,” Matt replies, more to us than his guides. “They always want meat. I don’t like it when those guys are around, but as long as things are stable among the cartels, we’re safe. The problems happen when there’s an upset in power and a new cartel tries to move in. I had to cancel a whole season several years back because of that. There’s probably more of them up on some of these hills, keeping watch.”

I should probably be concerned at this moment, but travel always includes a degree of danger. It’s true no matter the destination; I pass a car accident every few days on my way to work. Sure the presence of drug traffickers puts me on edge, but risk lies at the heart of adventure. Who knows what I’ll see down here? Let’s go hunting.

Two Sides

That afternoon as we make our way to a lookout, Old Mexico delivers what may be the biggest shock of the trip. We’re crawling up a bumpy grade cut into the side of a hill in Matt’s truck when our guide stomps the brakes with no warning. Rachel and I lurch forward.

Instead of an explanation or an apology, almost under his breath Matt utters, “That’s a huge buck! Shoot him now!”

This time it takes me only a split-second to find the deer. The buck is standing in an opening across a ravine, maybe 80 yards from the berm. I slip out the door and amazingly the buck is still there as I reach the corner of the fender. He’s in the shade, and he thinks he’s hidden. One bullet through the top of his heart sends him crashing on a short run through the brush, and then he lies still.

“That never happens!” shouts Matt from the cab. “What did you do, Adam? He’s a monster!”

Now it’s time for Matt, chill in the face of the type of situations south of the border that regularly make the news, to show some emotion. He radios Steve and Mario, relays the success and almost beats me across the ravine to the buck.

“He’s a teener for sure,” Matt says, assessing the buck’s rack. “I can’t believe he was standing there, along the road, in the open, just as we passed by. That never happens!”

“It was simply a case of the right place at the right time,” I say. “I’ve blanked enough times on animals far easier to find than Coues deer to know that I should never pass up a shot like that. I know you’re good, but I’d rather be lucky.”

Rachel and I dress the deer, and then Matt offers advice on getting the buck to the truck. He tells me to stoop down, and he’ll put the whole deer across my shoulders. “Really?” I ask. “That’s easier than dragging?”

“It might not be easier, but it will keep him out of the cactus,” he explains. “You don’t want to get that stuff in his hide, because it will be in your hands and everywhere when you skin him.”

We quarter the deer back at camp, and the meat feeds us for the rest of the week. We grill the backstraps, stuff burritos with the shoulders, smoke the hindquarters and carry pieces of them in our pockets to chew on while glassing. Before the trip is over we spot dozens of deer, and two more bucks and a bobcat fall to our group. The steady trickle of travelers heading north continues; by the end of the week, we’ve seen more than a hundred. The drug cartel guard vanishes into the hills.

We cross back into the United States at El Sásabe, the small border town where smiling kids play soccer in the sunny streets and la policía occasionally find decapitated bodies beyond the squalid outskirts. Depending on the moment, the view, the perspective, Mexico can be beautiful and fun, or ugly and dangerous. With Sonora now at my back, I realize how much my appreciation of one side has been heightened by my exposure to the other.