A few years ago, thanks to a Friday afternoon trip to Costco, I knew a major wave of mallards had suddenly hit town. Strings of 50-200 ducks poured into an adjacent wheat field, no doubt originating from a small refuge 10 miles to the west. I figured getting access to that field was futile, but I did have public access to the river just east of the refuge, which could place me squarely underneath their flight path. When you know where ducks are roosting and can locate a hot feeding site—even if you can't hunt there—two huge components of a good hunt have just fallen into place.

I don't look a gift horse in the mouth, so by 3 the next afternoon I had two dozen decoys resting in a slack channel, while overhead flights of mallards streamed to the east on a 20 mph wind. The big question was whether they'd return to the refuge before legal time ended.

A half-hour later ducks started trickling back, and just like I'd hoped, they were flying low, loaded with grain and struggling against a stiff headwind. I normally wouldn't have had much of a chance being so close to the refuge, but with the wind in my favor, lots of calling to grab their attention and to keep them on line—not to mention some strategically tossed rocks to churn up the water and add commotion to my spread—I managed to peel off ones and twos from passing flocks.

By sunset I was on my way back to my truck, feeling particularly smug about the limit swinging from my duck strap. Each drake had traveled the last hundred-plus yards on cupped wings, totally committed down to the final 10.

I've had lots of great duck hunts with far greater numbers hovering over the decoys, but that afternoon still ranks as my favorite. When you pull off a quality hunt from thin air—without tons of decoys and in a make-do, but not necessarily great, location—it makes you feel like you really accomplished something. More to the point, when you don't have time to scout out the "X" and don't have a trailer full of decoys, it's oftentimes what you have to do if you're going to get your share of decent weekend hunting opportunities.

Be Aware of What's Happening Around You

Every waterfowler knows that scouting is the single most-important component to consistent success. Nothing rivals the information you can gather by driving around the countryside to find out exactly where birds are feeding and roosting. Yet if you're like me and can't always spare the time between your job and other commitments, it's really a moot point. Then what do you do?

For local hunting opportunities, nothing beats simply paying attention to bird movement when you are driving around town. Like my trip to Costco, scanning the sky, water and fields might give you all the pieces to the puzzle. Plug that information into what you already know about your area from past hunting seasons and your game plan will take shape. For instance, I knew when lots of mallards show up in the valley, chances are they're roosting at the local refuge. And since I could see where they were feeding in great numbers, I knew where I could get under their flight path (the river).

But don't just rely on your eyes. Keep in regular touch with your hunting buddies and with local farmers whose land you hunt. I also get lots of good tips from friends who don't even hunt, but know I do. The point is, the bigger your network, the more eyes are out there scouting for birds.

Scouting Long-Distance, From Home

Scouting Long-Distance, From Home

Hunting destinations far from home can often be scouted by telephone. State fish-and-game offices are great sources of information that many hunters fail to fully appreciate. Perhaps I'm spoiled here in Montana with our super hunter-friendly Fish, Parks and Wildlife, but I'm betting most states' biologists and conservation officers are equally helpful. Ditto national refuge managers, many of whom are hunters themselves and can not only tell you when a major influx of birds has occurred, but can also turn you on to surrounding public hunting areas.

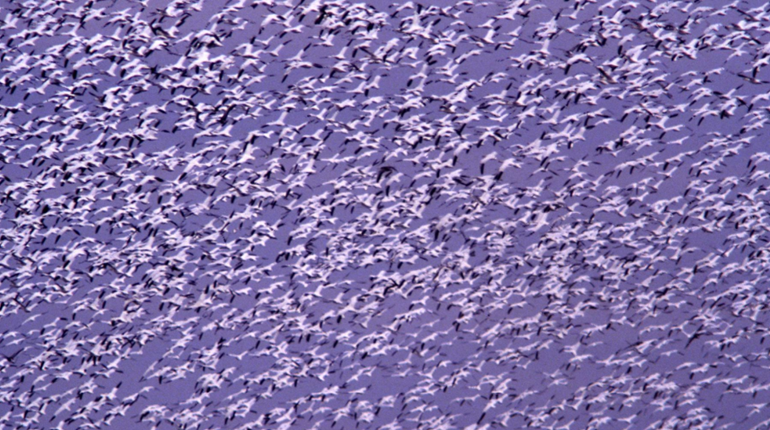

National refuges tend to encompass some of the larger bodies of water in a region and are refuges precisely because huge numbers of waterfowl stage there. Which is where Ben Cade, Avery Outdoors pro-staffer from Buffalo, Minn., will turn first when hunting an unknown area.

"Larger bodies of water will usually hold the biggest concentrations of birds, so that's where I start looking," says Cade. "Then I can follow birds to feeding areas and also locate transition areas, usually smaller bodies of water like sloughs and creek bends where the ducks will loaf in between roosting and feeding. Sometimes all you need is a slough with a hundred ducks on it. Push them off, set out a few decoys, and they'll often trickle back. You don't necessarily need a mob of ducks to have a quality hunt."

Scouting from home can also be as simple as reading destination pieces in magazines and checking out duck-hunting sites and chat rooms on the Internet. I'm always amazed how willingly some waterfowlers share every detail from their latest hunting trip—often to the dismay of local hunters, but a potential boon to you. And don't overlook birding sites. From one such site I get up-to-date information about every species of duck at a refuge three hours from my home, anytime I need it.

Kelley Powers of Union City, Tenn., owner of Final Flight Outfitters, likes to get a bird's-eye view of any area he plans to hunt. "Google Earth can give me the whole picture and help me visualize what the birds are seeing. For instance, if I can find two large bodies of water," says Powers, "I can then look for cornfields in between that might be great spots to hunt. Or I can look at a refuge and see what public areas might be around it, then get ideas of where the fight paths might be. If you can't scout from the ground, chances are you're not going to be hunting on the ‘X,' in which case the next best thing is being under the birds' flight path. And that's where seeing the broader picture via Google Earth can really matter."

Be a Weather Watcher

There's a reason The Weather Channel sees more time in most duck camps than ESPN: Waterfowl movement is intricately tied to weather. When it's warm and still, ducks don't need to feed as much, and they can raft up in the middle of large bodies of water all day. This means they're less active, creating fewer hunting opportunities. Conversely, strong winds and cold fronts will get them moving, seeking shelter in protected waters and feeding more actively. What does this have to do with weekend hunters? Potentially everything.

"If you can only hunt one weekend day, pick the weather day," advises Cade. "Don't pass up cold, windy days when major migrations happen and when birds are naturally going to be moving more." It's simple math: The more birds in the air, the more opportunities you'll have, especially if you didn't have time to scout out a specific hotspot.

Take full advantage of cell-phone weather apps with hourly forecasts. Sudden turns in weather can make or break your hunt. If temperatures are forecast to plummet overnight, that pothole you were going to hunt may be iced over, but riffles on a nearby river, or a warm-water creek, could be packed with birds. A drastic change in wind direction could have refuge ducks heading out to feed in exactly the opposite direction from the morning before. When you can only hunt one day a week, weather watching becomes all the more critical.

Maximize Your Spread's Visibility

Even if you're fortunate to hit a big migration day, your decoys can only do their job if they're visible. Obviously, the closer you are to a flight path, the better chance you stand of being seen. But even at distances up to 1,000 yards, you could still be in the game, although decoy placement, color, size and movement will play crucial roles.

Lots of hunters fail to take into consideration such things as tree lines and shadows. According to Powers, you don't want to set up in shade. Only in sunlight will the decoys' whites and darks create the contrast necessary for long-distance detection. Also, on a clear day it's hard for passing ducks to see details in the shadows, and your decoys will blend in, not stand out. Always look where the sun will be relative to tree lines and set up accordingly. Tree lines can also block ducks' line of sight, something to be mindful of especially if you're a river hunter.

If you're hunting reservoirs, points are a great place to set up if the wind isn't too strong to make placing your decoys there unnatural. Ducks trading up and down will typically pass closer there than back in a cove, for example, and birds can see your spread from pretty much any direction.

Powers and Cade enhance their spreads' drawing power by adding contrast and size. Both live in areas where Canada geese mix with ducks, and due to their size, plus black necks and heads and white rump patches, goose decoys can be seen from a long way off. In Minnesota, Cade says even divers and woodies are drawn to a Canada spread on water, and in fields they're super effective for mallards. Powers thinks they're so effective that "even if I'm just duck hunting, I'll use 90 percent goose floaters because they're so visible. But if I'm hunting where there aren't any geese, I like over-sized duck decoys, and the bigger the better. I'd rather have three dozen super mags than 1,000 standard-sized decoys." If you're a walk-in river hunter like me and can carry at most two dozen decoys, mixing divers into your spread is an easy way to add white for greater contrast and visibility.

The most effective way to draw attention to your decoys is to add motion. Spinning wing decoys are deadly in any duck spread, but especially in fields, where literally one spinner can sometimes be all you need. Cade uses Wonder Duck flappers on water, which churn up the surface and send out ripples, making the decoys look alive. Ripples also reflect light in more directions, helping to attract ducks' attention at long distance.

If you're a more traditional hunter like me, jerk cords, and even sticks and stones in a pinch, will also make a spread come alive. If you use a jerk cord, really rip on the cord when you first spot distant ducks for maximum water-surface disturbance. When the ducks get closer, then you can move your decoys more naturally.

The same idea holds for calling, which is a critical component to any on-the-fly duck hunt: To grab passing flocks' attention, blow loud and aggressively. Once you turn them, tone down the intensity. Not being on the "X," you might have to call way more aggressively than normal to keep birds on track. Then again, as Kelley Powers cautions, with luck you may end up exactly where the ducks want to be, in which case loud calling could spook, not attract, birds. Let the first few flocks you see be the litmus test; whatever works on them should work the entire hunt.

Be an Opportunist and Act Fast

In fact, because you'll be set up where you think birds will be, but without any confirmation from on-the-ground scouting, those first flocks should always determine what you do next. There's a good chance you won't be in the right spot, and if ducks (or geese) confirm your suspicion, be prepared to change your whole game plan. If successive flocks ignore your spread and land anywhere you can go, pick up the decoys and move. A morning flight only lasts so long. Or if the ducks land too far away, try to be there the following morning. The point is to be an opportunist and take advantage of whatever knowledge you can glean on the spot.

Similarly, don't look a gift horse in the mouth. If you see an opportunity materialize like I did that afternoon I went to Costco, try to take advantage of it as soon as you can. The ducks might be gone two days later. Or if you flush a bunch of ducks from a pothole on the way to your intended hunting spot, consider hunting there instead. Hunting by the seat of your pants may not be anyone's first choice, but when you're tight on time and don't have the luxury of on-the-ground scouting prior to the weekend, being flexible—and acting fast—will more often than not be plenty good enough.