Whether you may feel technology is the driving force behind the change in bullet technology, or the recent legislation in a number of states which calls for lead-free projectiles only, there is no doubt that the copper monometal bullets are here to stay. But are they so good that they warrant abandoning lead-core ammunition altogether? Or are those lead core designs—at least in those areas where they are legal—just as valid as they were years ago? Let’s take a look at the pros and cons of each style.

The good old lead core/copper jacket design has been with us since 1882, when a Swiss Colonel by the name of Eduard Rubin introduced the world to the full metal jacket bullet. Adding a jacket of copper gilding metal—harder than the lead core, yet still malleable enough to be engraved by the barrel’s rifling—allowed the projectile to be driven to higher velocities, as well as resulting in improved terminal ballistics. For the hunting world, the jacketed bullets had either a hollowpoint or a bit of exposed lead at the nose, both concepts employed to initiate expansion.

The Hornady InterLock roundnose cup-and-core bullet shown in profile and in cross section.

The Hornady InterLock roundnose cup-and-core bullet shown in profile and in cross section.

As velocities increased—smokeless powder being implemented at the end of the 19th was a big help—stronger projectiles were developed to combat that speed, as often the jacketed bullets would exhibit premature bullet breakup, especially in speedier cartridges. The year 1939 saw both Remington’s Core-Lokt and Winchester’s Silvertip enter the market, both in an effort to slow expansion and reduce the risk of jacket/core separation; the former used a groove in the jacket, pressed into the core, to keep things together, while the latter used an aluminum cap over the nose slow expansion.

Though the shortcomings of the early lead-core bullets led to an entire market—names like Nosler, Jack Carter’s Trophy Bonded Bear Claw, Swift and other premium bullets came to light as a result—in a multitude of applications a standard cup-and-core bullet will work just fine. I’ve taken a wide variety of game animals with a simple jacketed rifle bullet; though some had polymer tips, the principal is the same. For varmints and furbearers I prefer frangible bullets with thinner jackets, and for big game species I like thicker jackets and a bit more sectional density. The Remington Core-Lokt, Hornady InterLock and ELD-X, Speer HotCor, Nosler Ballistic Tip, Sierra GameKing and Winchester Power-Point have all been good, on game animals from pronghorn, whitetail and black bear, up to mule deer, caribou and elk.

The Texan wild boar fell to a single Hornady 140-grain cup-and-core from a .275 Rigby.

The Texan wild boar fell to a single Hornady 140-grain cup-and-core from a .275 Rigby.

The cup-and-core softpoint bullet is built for expansion, but there can be too much of a good thing. A light-for-caliber bullet delivered at high speed will see explosive expansion, and poor penetration, as the projectile can actually come apart. Jacket/core separation is a reality, but there are means of combating that. Bullets with a partition between two separate lead cores—namely the Nosler Partition and Swift A-Frame—keep the rear of the bullet intact while allowing the front to expand, giving a good balance of both features. Chemically bonding the core and jacket is a great method of nearly eliminating chances of bullet failure; even when penetrating thick hide and large bones. The Trophy Bonded Bear Claw, Swift Scirocco, Woodleigh Weldcore and Hornady’s DGX Bonded are all great examples of bonded bullets, and all have a great reputation when pitted against tougher game species. Retained bullet weight is very high, expansion is reliable, and penetration into the vital organs of even the largest species is no issue.

A 250-grain bonded core Woodleigh Weldcore recovered after penetrating an old kudu bull lengthwise; bonding the core helps prevent jacket/core separation.

A 250-grain bonded core Woodleigh Weldcore recovered after penetrating an old kudu bull lengthwise; bonding the core helps prevent jacket/core separation.

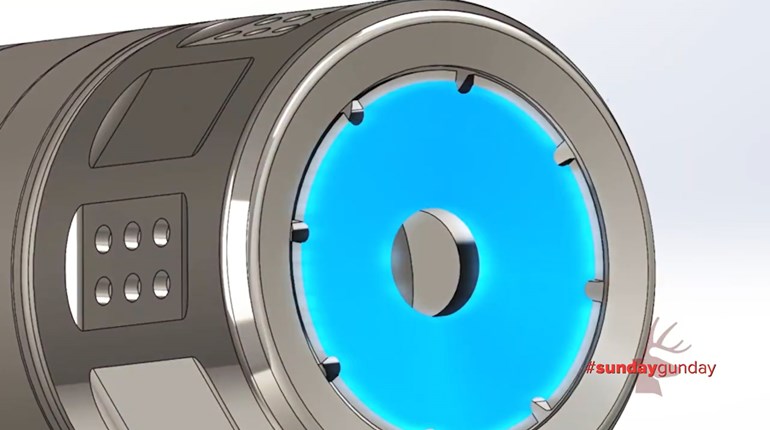

In the quest for a bullet which wouldn’t breakup, Randy Brooks—then the owner of Barnes Bullets—had the brilliant idea of removing the lead core altogether, leaving a projectile made entirely of gilding metal. The Barnes X was quite the radical concept when it came onto the market in 1989, and being honest the original design didn’t agree with my rifles at all. Grooves were added to the shank of the bullet, to reduce bearing surface and minimize copper fouling as well, and that made a huge difference in performance. In the 35 years since the Barnes X came onto the market, nearly all the major manufacturers offer a copper monometal bullet of some sort. The Winchester Copper Impact, Remington Core-Lokt Copper, Federal Trophy Copper, Hornady CX, Norma EcoStrike and Nosler Expansion Tip all share many of the same characteristics: high weight retention, reliable expansion, and because of the integrity of the design, deep penetration. These bullets have neither jacket nor core so there’s nothing to separate—with the exception of the Cutting Edge Raptor and the Lehigh Defense Controlled Chaos, which are both designed to have the front section of the projectile break apart to intentionally cause trauma.

A trio of Peregrine BushMaster monometal bullet from the 470 Nitro Express, recovered from some Cape buffalo in Zimbabwe; they were found against or near the offside skin.

A trio of Peregrine BushMaster monometal bullet from the 470 Nitro Express, recovered from some Cape buffalo in Zimbabwe; they were found against or near the offside skin.

Looking at the differences between the two designs, you’ll immediately see that a copper bullet of the same diameter and weight with be longer than its lead-core counterpart; this is simply because lead is denser than copper. The center of gravity of a copper bullet will be a bit more rearward than a lead-core bullet, and for that reason there are times where the traditionally heavier bullet weights for a bore diameter can’t be properly stabilized. But that’s mitigated by the fact that a copper bullet of lighter weight will often mimic the terminal performance of heavier lead-core bullet. For example, on a plains-game safari to South Africa, I loaded 150-grain copper monometal bullet in my .300 Winchester Magnum, where I’d usually load a 165- or 180-grain, and had no issues at all. Both a kudu bull and a waterbuck bull fell to a single shot from that .300 Winnie, and I wouldn’t hesitate to use that combination again for plains game.

This past fall I used a bespoke rifle from Todd Ramirez in 9.3x62mm Mauser, loaded with 286-grain Barnes X, for deer and black bear. Despite being a bit on the heavy side, I had the opportunity to take a good eight-point whitetail; the deer dropped to the shot, and surprisingly I recovered the bullet. It had expanded 1.68x original diameter, and retained 100 percent of its weight. I had used the same rifle three months prior, this time handloaded with a 286-grain Hornady InterLock cup-and-core, to take a good tom leopard in Zimbabwe. I opted for the lead-core bullet for the leopard as I felt it would give more expansion upon impact on the thin-skinned cat, and chose the stiffer Barnes-X for the New York season because there was a very large black bear sighted on the property I hunt in the Catskills, and felt that copper monometal hollowpoint would handle the largest of black bears. In fact, that 286-grain Barnes X would handle, and has handled, game animals as large as grizzly bears and Cape buffalo.

The Barnes TSX, a derivative of the original Barnes X, first expanding bullet design without a lead core.

The Barnes TSX, a derivative of the original Barnes X, first expanding bullet design without a lead core.

If your hunting area mandates that you must use lead-free ammunition, don’t feel that you are necessarily missing out on something. Nor should the hunter who has spent a lifetime using a tried-and-true lead core bullet feel that there is some sort of magic in a lead-free monometal. In the opinion of the author, the situation at hand and game species pursued can best dictate the type of bullet chosen. For example, I've taken Cape buffalo cleanly with both varieties of bullet, albeit the lead-core bullet was the bonded and partitioned Swift A-Frame, and the monometals were the South African Peregrine BushMasters—both are stiff, rugged projectiles and both worked wonderfully.

On a lighter species like whitetail deer, I generally opt for the lead-core projectiles, as the majority of them transfer their energy a bit faster than the majority of monometals do, and the deeper penetration isn’t really required on those species. For thick skinned animals and larger species, I have no issue with the monometal performance, as I feel it does offer an advantage, removing the concerns of premature bullet breakup or any penetration issues. Looking at things financially—like all else, the price of ammunition and component projectiles have certainly increased—the lead core bullets will almost always be more affordable, and depending on the volume of shooting you do, that may be an important factor.

A bunch of Swift A-Frame bullets recovered from African game animals. This bullet has a partition of copper separating dual lead cores and the front core is bonded.

A bunch of Swift A-Frame bullets recovered from African game animals. This bullet has a partition of copper separating dual lead cores and the front core is bonded.

The bottom line here is that while the copper monometal bullets do have their own unique characteristics and performance traits, a hunter could spend the rest of his or her days in pursuit of game, big and small, without issue. On the flip side of that coin, the copper jacketed, lead core bullet is better than it ever has been, and despite the political efforts to demonize lead-core projectiles, that formula remains one of the most efficient and economical means of filling your freezer. As an unabashed bullet junkie, I use both varieties, and will continue to do so as long as they remain legal for hunting.