I have always lived by the philosophy a person can’t have too many guns, books or knives. So, for a while now I have lusted for a Damascus steel hunting knife, and that desire was fueled even more after I used a loaner knife from custom maker Gordon Romeis during last year’s hunting season. His knife performed extremely well for field-dressing, skinning and quartering whitetails. But then again, a lot of knives can do that. What the bland store-bought knives can’t do is make your hunting buddies gasp with surprise when you pull them out of their sheaths. A knife that makes people gasp is not just a tool; it’s also a piece of art.

I get a lot of joy in life by puttering in my shop. Like my buddy Randy Brooks of Barnes Bullets says, “I am happy with concrete under my feet.” Usually I am tinkering on guns, but I had a wild thought and decided to build a Damascus blade hunting knife.

Guys like Gordon get their metal in a billet and remove all the parts that don’t look like a knife blade. Damascus steel is extremely expensive, so for my first attempt I took a more manageable approach. I went to Jantz Supply, a well-known company for knife building kits and components, for some help. I have a little experience with Jantz as my son Nathan and I built a Bowie knife from a kit I bought for his 10th birthday. Then, because Dad didn’t have a Bowie, we built another for me. They were great father-son projects that resulted in some pretty cool looking knives to wear on our belts back in our cowboy action shooting days. But this project was going to be a bit more complicated.

The knife on the 2013 Jantz catalog cover was absolutely striking and was similar to what I wanted to build. The 31/2-inch blade, pattern No. 22, is one of the most popular pre-shaped knife blades offered by Jantz, so I ordered one in Damascus. I also ordered a set of pre-cut desert ironwood grip scales. The knife on the cover used Damascus bolsters, but they only come in blocks rather than pre-shaped and drilled. As this was my first project, I chickened out and ordered brass pre-cut and drilled bolsters.

The knife on the cover used some striking spacers between the bolster and grip, which I wanted to duplicate. So I ordered sheets of brass, nickel silver and black spacer material.The handle screws are contrasting brass and silver, and I wanted to duplicate the pattern in reverse on the bolster. But the mistake I made was that the screws that would have been the brass center were gold-plated steel, not solid brass. I didn’t discover that until they were installed and it was too late (one of those little things I’ll remember next time). Lastly, I ordered a leather scabbard.

Install, Shape the Bolsters

After degreasing all the parts with Outers Crud Cutter degreaser, the first step is to install and shape the bolsters. Actually, the first step is to polish the front edge of the bolsters, because it’s nearly impossible after they are installed.

If I were going to use full-length bolster pins, the process would begin by shaping the bolsters close to finished size, then counter-sinking the pin holes slightly. The pins would be cut and peened to fill the holes. Then the final shaping and polishing would be completed. But as I was doing the cosmetic pins, I cut the main pins short and glued them into the knife blade so they filled half the depth of the bolster holes. This allowed the pins to do their main job, which is to align the bolsters and protect them from impact forces. I glued the bolsters in place, clamping them tight while the epoxy set. When the glue was completely cured I shaped the bolsters.

Before starting the shaping process, I covered the blade with two layers of painter’s blue masking tape. I also left in place the point protector shipped with the blade. This protected my hands and it helped protect the blade if I slipped and hit it with a sanding belt. Then I glued in my cosmetic stainless steel threaded tubes and (I thought) brass screws. After the glue dried I cut these as close as possible to the bolster with a Dremel cut-off wheel.

I am not a professional knifemaker and I don’t have the specialized equipment guys like Gordon own. But I have more time to spend on each knife than they do and a shop full of other tools with which I can improvise.

With any project it’s always easy to remove more material if you do not remove enough, but impossible to put it back on if you take too much. So, I used a 120-grit belt and worked slow.

I squared up the back of the bolsters with the blade. Then I brought the other edges of the bolsters and tang all flush. Sanding with a belt generates a lot of heat and heat will cause epoxy glue to release, so work very slowly and dip the knife in a bucket of cold water every few seconds to dissipate the heat. You do not want the metal getting too hot to handle. That’s the cue: If it’s too hot to hold in your hand, it’s too hot.

To shape the inside contours, I bought a 7/8-inch-diameter sanding mandrel to chuck in my drill press. I think it cost me something like five bucks on clearance, and it came with several extra sanding disks.

Once the edges were all flush, I started to shape and contour the bolsters. I know pros like Gordon use a long, unsupported sanding belt so the belly in the belt helps give them the shape they want. All I have is a combination belt and disk sander that is common to most shops. I found that if I removed the backing plate from the belt sander I had 11 inches of unsupported belt. The belt on mine is 2 inches wide, and while 1 inch would have been better, you work with what you have.

By working with the belt sander and using the round sanding mandrel in my drill press, I was able to carefully shape the bolsters.

Build, Shape the Spacers

For the spacers, I cut a 1-inch strip off each of the spacer plates, degreased them then coated them with epoxy. I clamped this laminate in a bench vice and left it for a day to cure. I squared up one edge on my 8-inch disk sander and then used a hacksaw with a 20-tpi blade to cut out a couple of small pieces. I glued these to the knife against the bolsters, keeping the square edge against the knife blade and clamping them in a small vice. When the glue was dried, I shaped them to the bolsters by working very carefully with my belt sander.

All I can say about that process is there has to be a better way!

The concept was sound enough, but the epoxy glue kept letting go. It really didn’t like the black plastic spacer material, and the metal pieces got hot very quickly due to their tiny mass, so nothing stayed stuck. I re-glued the parts and pieces several times. I even had to replace a few pieces. For the record, I also said an incredible number of bad words.They say one measure of insanity is doing the same thing over and over, expecting a different result. At some point I realized “this ain’t working” and switched to super glue. That worked better, except for the part where I glued my fingers to the bolsters, which slowed things down for a while. In the end, I have more time in making and fitting these spacers than I do in the rest of the project.

I later learned that the man who built the knife on the catalog cover drilled holes in the bolsters and spacers using a milling machine, and fitted pins to keep them all behaving. Next time I’ll do that. While I have a milling machine, I don’t see any reason why a drill press can’t do it just as well.

One other point: I duplicated the spacers on the cover knife, forgetting he had them against a Damascus bolster. Mine fit against a brass bolster, and the first spacer is hidden because it is the same material as the bolster. I should have alternated my pattern so I didn’t have brass against brass. But in the end, all that aggravation was worth it as I think the spacers add a touch of elegance to the knife.

Fit the Handles

The ironwood handles must be shortened to allow for the spacers, but care must be taken to keep the angle on the face correct or there will be a gap when they are fitted. The best way is to make a scribe mark just short of the final length and then quickly grind off the excess using a course disk sander and stopping at that mark. Then carefully fit the handles, taking off a small amount of material with a fine-grit belt. Watch the angle to make sure the handles will fit flush against the spacers and can still be fitted to the tang correctly. Take your time, work very slowly and get it right, as you only get one try.

Install, Cut and Shape the Bolts

The next step is to coat the tang, handles and Loveless bolts with glue, including the edge of the spacers. Then fit the handles to the blade tang and tighten the Loveless bolts, making sure the handles overlap the tang everywhere and fit tight against the spacers. Just to be safe, I also added a few clamps while the glue set.

I have never been good with sticky stuff; glue was spurting out all over the place. It coated my hands, the bench and my tools. (I swear I could walk by mixed epoxy, keeping my hands in my pockets, and still get them sticky.) I even got some in my hair. Of course, any overflow on the knife won’t hurt a thing as it will be sanded away when doing the final shaping and finish. But the rest of it made a huge mess, something I have come to expect every time I get near gooey liquids.

After the epoxy cured, I used a hacksaw to cut off the protruding Loveless bolts close to the handles. I used a file to take them down flush with the wood and to shape them to the curve of the grip. Then I used a few more files to take the grips down flush with the tang. A flat file worked best on top; I used a half-round file for the curved section under the grip and for the contour on the end. I suppose the belt sander would be faster, but you’ll be less prone to mistakes or accidents with a file.

Shape, Finish the Handles

Next, I shaped the handles using my belt sander with the backing plate removed. Gordon had warned me to be careful when working around the metal of the spacers, bolsters and Loveless bolts. The metal is much harder than the wood, and the wood can be removed faster, causing a dishing effect. I found out he was right. Work slowly here and watch everything. There is a tendency to focus on what you are doing and not notice that the sanding belt is hitting other places as well. (Don’t bother asking why I know that. It was a first project, mistakes happen. I fixed it and the pain is fading. Let’s just move on.) Just believe me when I say go slow and pay attention.

When the shape is right, hand-finish the handles with decreasing grits of sandpaper. Finally, use a cloth buffing wheel with several compounds in decreasing abrasiveness to polish the metal to the sheen you desire. The tang and spine of the knife will buff out to a mirror polish. Or you can do as I did and leave some of the Damascus folds showing.

Clean the buffing compound off the knife, including the wood. I found that Outers Crud Cutter works well for this. Once you have it all removed, finish the wood.

You can stain it first, but I used Chem-Pak Pro Custom Oil Gunstock Finish from Brownells without stain. This is a tung oil and urethane blend. I have had great luck with this finish on gun stocks as it penetrates and fills pores as well as coating and protecting the wood. I put on several coats, lightly sanding with steel wool in between coats. I finished by hitting it lightly with very fine steel wool for a satin finish.

Other than sharpening the blade, the knife is now done.

Be very careful while sharpening not to contact the blade with the abrasive anyplace other than on the edge. Scratches are tough to remove on any knife, but really complicated on a Damascus. (Please don’t ask me how I know this. Like I said, I prefer to forget some things.)

Case, Finish the Sheath

You could put everything I know about leatherworking in your pocket and never notice a lump, so I was a bit apprehensive about this part of the project. The remarkable thing is I simply followed the directions supplied by Jantz and it turned out just fine.The sheath is pre-made, but needs to be “cased” and finished.

To case it, coat the knife with a protective film of grease or oil and wrap it with clingy plastic wrap. Soak the knife case in hot tap water for about two minutes. Then remove it from the water, insert the knife and use your fingers to form the leather around the knife. Keep doing this until the leather starts to take a set. Let it set for about 10 minutes and make sure the leather is still formed, pushing and prodding as needed. Then set it aside until it is dry.

Once the leather was dry, I stained it with leather stain I bought at a local hobby shop. I made a mistake in getting dark brown and my leather turned out much darker than what the picture in the store showed. I wish I had bought the light brown or just skipped that step, as the oil will darken the leather. When the stain was dry, I slathered neat’s-foot oil on the case. I put on several coats, letting each one soak into the leather.

The edge where the leather is sewn together needed some attention. I Googled how to do that and got far too many ideas. I remembered reading about the old-timers “boning” the edges. So I wet the edge and rubbed it with an old bone I “appropriated” from my dogs. It worked like a charm, smoothing the leather, filling the gaps and putting a radius on the edges. I bought some overpriced bee’s wax from the same hobby shop and used the bone to work a little into the edge of the case for a final, smooth, glossy finish.

The Parts and Pieces

Jantz sells kits starting at less than $20 for an entire knife and sheath. The materials to make a complete Pattern No. 22 knife start at less than $55. The sheath is $14.50 more.Of course, I decided to go top shelf with everything. Damascus steel is very expensive, and ironwood is one of the most expensive handle materials. The cost for materials for my knife was $182.43. But $34.09 of that was for the spacer materials, which was enough to do a lot of knives. A comparable knife from a custom maker would run $300-$400, so I saved some money. Plus I had a lot of fun putting it all together. Now when I pull it out in camp and somebody goes all swoony eyed with envy I can casually say, “Yeah, I made it myself.”

Jantz Supply

309 W. MainDavis, OK 73030800-351-8900

[email protected]

The Alternative

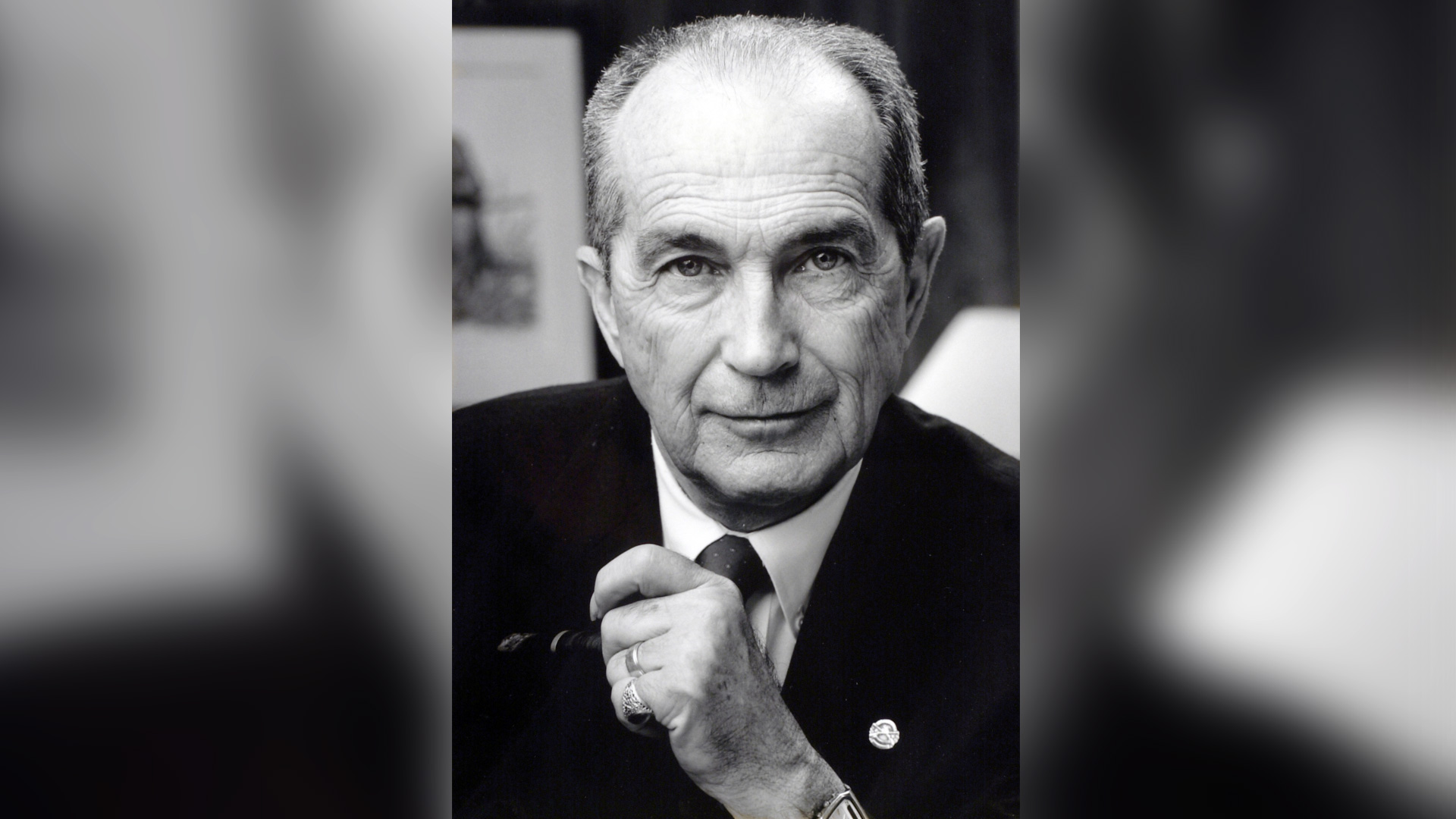

You can skip the aggravation of making your own knife and of course buy a custom unit from a professional knifemaker like Gordon Romeis. I have used several of Gordon’s knives; his craftsmanship is outstanding. In fact, one of his knives inspired this project.

Gordon Romeis

1521 Coconut DriveFort Myers, FL 33901

239-940-5060

[email protected]