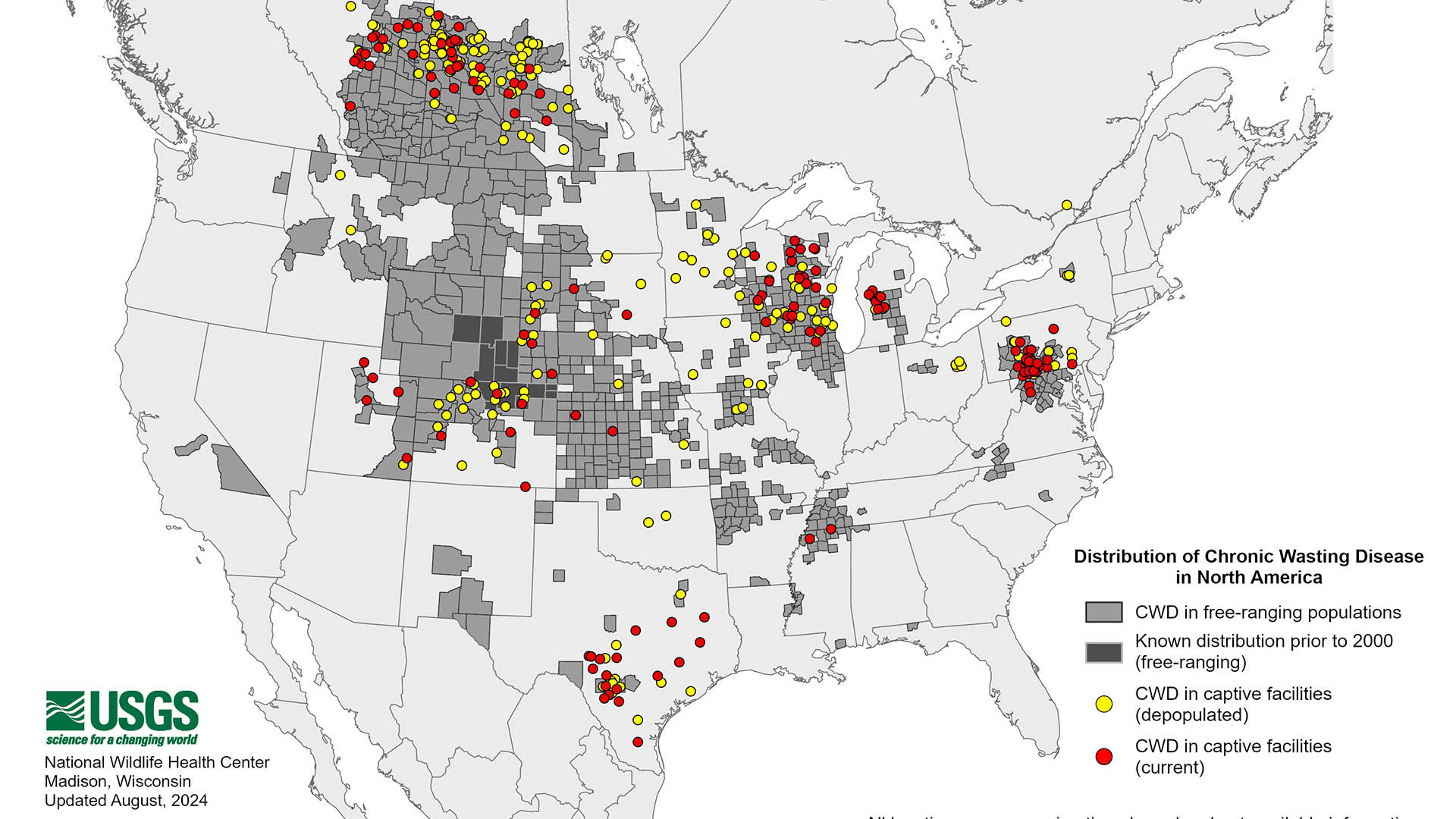

The U.S. Geological Survey National Wildlife Health Center (NWHC) released its latest chronic wasting disease (CWD) map—seen above—last month. It noted that currently, “Chronic wasting disease has been detected in free-ranging cervids in 35 U.S. states and four Canadian provinces and in captive cervid facilities in 19 states and three provinces.”

Hunters in pursuit of cervids need to stay up to date with the latest information on CWD in their state and be knowledgeable on the symptoms. In addition, restrictions on transportation and importation of game meat are common in some areas. Regulations are modified often to contain the disease.

A study underway by NWHC indicates we can expect more changes. A December press release summarizing findings of research in Wisconsin states, “Preliminary findings from the study suggest continued spread under a status quo management scenario and that a suite of intensive and prolonged management actions is likely needed to achieve stabilization or disease reduction in Wisconsin. However, some of the actions identified as potentially effective are currently unavailable due to jurisdiction and resource constraints in Wisconsin.”

CWD was first detected in Colorado mule deer. The year was 1967, and it has since defied government eradication efforts. It is not confined to North America, either. Cases have been confirmed in Europe and at least once in Korea—after deer were imported from Canada.

Infected cervid behaviors and appearances are detailed in a Texas Parks and Wildlife fact sheet [PDF]. “Symptoms of infected animals include emaciation, excessive salivation, lack of muscle coordination, difficulty in swallowing, excessive thirst, and excessive urination,” it states. “Subtle behavioral changes like loss of fear of humans or other abnormal behavior are often the first signs noticed. Clinically-ill deer may have an exaggerated wide posture, may stagger and carry their head and ears lowered, have dull expression, and have a seemingly shaggy hair coat.”

It also notes, “Researchers with the Federal Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, and along with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment, have studied CWD and have found no evidence that CWD poses a serious risk to humans or domestic animals. The World Health Organization (WHO) has likewise advised that there is no current scientific evidence that CWD can infect humans. However, as a precaution, the WHO and the CDC strongly advise testing susceptible species harvested in known CWD areas and to not eat meat from CWD positive animals.”