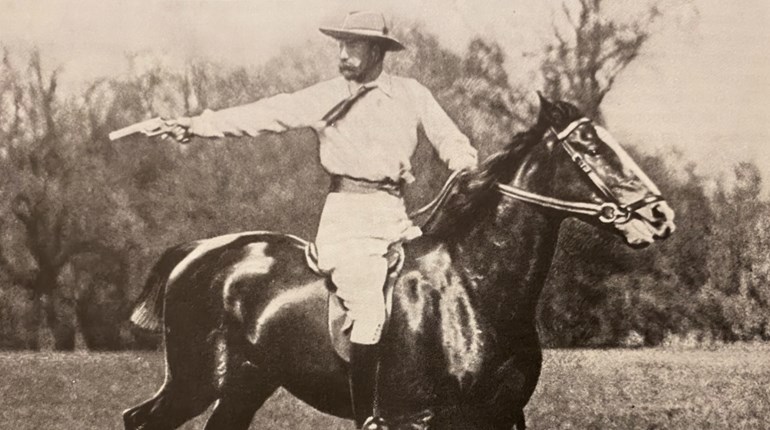

“. . . that old buck had to run, not because he was skeered, but because running was what he done the best and was proudest at; and Eagle and the dogs that chased him, not because they hated or feared him, but because that was the thing they done the best and were proudest at, and me and Mister Ernest and Dan, that run him not because we wanted his meat, which would be too tough to eat anyhow, or his head to hang on the wall, but because now we could go back and work hard for eleven months making a crop, so we would have the right to come back next November …”

Excerpt from ‘Race at Morning’

William Faulkner

“Just listen to any of the older guys around here and it’s all they want to talk about,” Scott Clark told me as he released a bawling Walker hound into the chase. “Dog hunting is a huge part of our Southern tradition and they are taking it away from us.”

He is right, of course. With hunting under attack from all quarters, dog hunting, particularly dog hunting for deer in the South, is a huge target. The drive to ban dog hunting is almost unique in that much of the opposition comes from other hunters.

That’s not to say that the argument doesn’t have validity on both sides, only that perhaps we as hunters should consider not eating our own quite so often. The divide-and-conquer strategy has been used in warfare since the dawn of man. Find a weakness and exploit it until it defeats your opponent. It’s basic stuff, but the basics are how you win. Ever read Sun Tzu? It’s working all too well against the things we hunters hold dear to our hearts.

For example, the antis found a weakness in trapping, and they exploited it. Most people didn’t trap. In fact, most hunters didn’t trap. It was easy to exploit trapping as cruel, and those who didn’t understand it were moved by the emotional arguments, even a lot of hunters. Trapping is all but gone today.

Now the antis have turned on hunting. They know that we are strong, so they must find the chinks and stab at them. One is hunting with hounds, not just in the South but all throughout the country. I live in the Northeast and have watched dog hunting for bears being whittled away by regulations, rules and social pressures. Collectively, bear hunters who use dogs are like the frog in the pan, and the water that will end the sport is approaching a slow boil. Sadly, I see other hunters turning up the heat. It’s not their sport, they don’t understand it, so they buy into the emotional argument that it’s somehow “unfair.”

In the South, perhaps the biggest factor in the war on dog hunting has been changes in how deer are hunted. With the rise over the past several decades of “still-hunting,” as hunting from a stand is called there, dogs have become a nuisance, rather than an asset. Dogs and deer do not understand human boundaries and property lines. If the chase goes past a hunter on stand he will become understandably upset. He has worked hard to keep deer on his property and to pattern the movements of those deer. Dogs that come through chasing the deer are seen as a problem, and little sympathy is generated for his neighbor’s preferred way to hunt.

As a result, the sport of hunting deer with dogs is seeing incredible pressure from not only the avowed enemies of hunting, but also from other hunters. The hard, cold truth is that it likely will not survive another generation, and that is a tragedy on so many levels.

Throughout our country’s history, sport hunting has been about so much more than just killing animals. It’s often about traditions, values, morals, family and friends. Deer camps are where important life lessons are taught. They are where strong family bonds are built, and it’s where boys would go to become men. Nothing in human existence is stagnant. Everything changes, and often that change is good. Once the stronghold of testosterone-infused men, social evolution has changed the traditions of deer hunting to where it’s now a family endeavor. Young girls learn the same values and morals along with the boys. With hunting under fire from all sides, it’s important that we are inclusive, and the relatively recent rise in women hunting is a good thing.

Hunting itself is changing, too. Dog hunting for deer was never so much about the trophy, but more about the social interaction with the hunters as part of the group. Today, deer hunting is becoming more of a solo event focused, some say too much, on success and antler inches, and less and less on traditions and social interactions. With these new changes in how and why we hunt, the important aspects of family, friends and tradition are fading from the equation.

One of the last bastions of this strong social construct is found with the dog hunters chasing deer in the Deep South. There is constant human interaction and there is always a social structure for those involved. Each hunter has a job and a place in the hierarchy. It’s through these interactions that so many of life’s best lessons are learned.

The loss of dog hunting, when it happens, will in so many ways reflect the loss of traditional America. When we lose those traditions that make us what we are, that instill important values into each generation, then we will lose one of the things that made us strong. I only wish more hunters would understand this and that we could all stand together and find a way to accommodate every aspect of our sport. We only need to remember the famous remark of Benjamin Franklin about the time the Founding Fathers signed the Declaration of Independence: “We must all, indeed, hang together or, assuredly, we shall all hang separately.”

We are humans and have all the faults and frailties that entails. We often can’t or won’t see the reality of a thing until it’s too late to reverse course. It’s evident that dog hunting for deer in the South is in its twilight years. There are many who believe the time has come for it to end, but I see it much differently and will stand with the dog hunters mourning the loss of the sport, but for other reasons. While I admit I love to hunt with dogs, the loss will be much more than just my personal interests. The loss will be one for all hunters, even if many are not able to understand that.

My interest in hunting with dogs has taken me on a lot of adventures. Black bears, mountain lions, coyotes, hogs, rabbits and more. But my deer hunting with dogs had been limited to one rather unsatisfactory day in Alabama two decades ago that lacked any true aspect of the traditions of the sport.

In the Deep South, tradition is a huge part of the hunting experience and I wanted to immerse myself in the true essence of dog hunting at least once before it fades away. When my friend Lee Hawes told me he had a connection in Louisiana and offered to secure an invite for me, I jumped on it like a hobo on a hot dog.

Something came up last minute, and Lee had to cancel, but Shane Vascocu said, “Aw hell, that doesn’t matter. Mr. Lee might not be able to make it, but there is no reason you can’t still come.” I knew right then I was going to like this guy.

The camp was all Southern, a “shotgun” style house evoked so often in Southern literature. In this case it was a “double” with one side of the long structure an open common area, including a kitchen. The other side, sharing a common wall, was for sleeping. Of course, there was a porch in the back for sitting.

When Shane and I arrived late Friday afternoon just a few people were at the camp, but as the evening went on more and more arrived. I know what a privilege it is to be invited to any private hunting camp and tried to keep a low profile without being standoffish. Hunting camps are sacred places, particularly on opening day. Just being invited by a member does not mean you will be accepted, but I found nothing but warm, open hospitality here.

The patriarch and owner of the camp is Joe Juge. This 80-year-old Southern gentleman was a wealth of stories and history regarding this part of the South. Food is always a big part of any Southern hunt. As Joe prepared dinner, I mentioned my attempts at cooking fried chicken never ended well. He then spent an evening instructing me how to properly prepare this traditional Southern dish, sharing all the subtle secrets that make his chicken so damn good. This kind of open sharing is how Southern hospitality is defined.

This is a family camp. Joe’s brother Dick had traveled from California for the hunt, a tradition he never misses. Joe’s son Jared Juge is tall and extremely fit. It turns out he is a physical fitness and nutrition expert who has graced the covers of magazines. His quiet manner covered his successes, and only after I asked did he share this with me. John Thibodeaux is quick with a joke and full of stories about growing up in the South. Scott Clark is the dog man. His son Rustin is the boy that every deer camp should have. They call him Beau, his middle name, and like a pup in training, he represents the next generation and the hope that these traditions will survive. Along with these men, William “Shane” Vascocu and his dad, William (Bill), and Bill’s dad, Troy (now 90 years old), have passed this dog-hunting tradition from generation to generation. Collectively, they all are the heart of this camp. Here, they are all family.

Rather than simply wait on stand, I traveled in a side-by-side with Scott and Beau the next morning so I could see the property and get a feel for the entire process of dog hunting. Once the dogs were out and the chase was on, Scott would drop me off on a stand. As the chase moved past, he would pick me up and we would go to the next stand.

In my mind I had expected this to be a bit like William Faulkner’s 1955 short story, “Race at Morning.” In some ways it was. The camp life reflected some of the bonding and camaraderie of the Southern deer camp. But the chase itself was much different, a victim of the changing times, and a bit stunted from the long, epic chases captured in that story.

This group used to have a huge property farther north where they hunted. There they could spread their wings and let the dogs work out long trails. But the lease was lost to others who wanted to stop the dog hunting and only “still-hunt.” Now they must hunt this smaller property near Bachelor, La.

With a sad understanding that their sport has been targeted, they are always aware of the neighboring property. Time and again Scott would catch his dogs, ending the chase because he was worried they were about to leave the property. Of course this limits their hunting success, but they want to preserve their way of life and know that keeping good neighbors is critical to that goal. They often erred on the side of caution, even at the expense of their own hunting experience.

We didn’t take any deer that weekend, and I suppose the fault rests on my shoulders. I can’t say that I made all that good of a showing for we Yankees in terms of hunting. I had an opportunity that first morning, but blew it with a spectacular rookie mistake.

Scott stopped the buggy at a small footpath and told me to find a good place to watch the opening I would find just down the trail. Before I could reply, he was off again.

I found a tower stand and waited at the bottom. I had already learned a hard lesson about getting into the box blinds. They limit what you can see and how fast you can move. For this kind of deer hunting you need to be aware of everything and to be able to move very fast—a lesson I would learn again in a few minutes.

I could hear the dogs heading my way. The next few minutes defined the essence of dog hunting. The anticipation that builds as you hear the chase closing in is unlike anything else in the world. I stood waiting and ready as the dogs, in full cry, came closer and closer, every nerve on alert, the hair on my arms standing on end, and my muscles quivering like a setter on point.

I felt the wind shift slightly to blow to the dogs. Fifty yards to my right the chase made an abrupt 90-degree turn, and 200 yards in front, it made another 90-degree turn. The deer had caught my wind, and was making a run around me and the long opening I was watching. Soon enough the chase was past me, off to my left and heading away.

I thought about a famous (fictitious) Southerner, Forrest Gump, and what he said just before he met the president: “I must have drank me about 15 Dr. Peppers.” In my case it wasn’t Dr. Peppers, but I had drank me a bunch of coffee. I was in dire straits, and it had not improved during the wait for the dogs. But now that the chase was by me I was safe to attend to my immediate needs. I didn’t want to pollute somebody’s deer stand, so I made my way some distance from it, all the while listening in disappointment to the dogs moving farther and farther away.

About the time I was well into the chore, a stick broke off to my left, and I heard something coming my way fast. A big doe broke cover and all but ran into me. She did one of those flip things that surprised deer do and backtracked about 10 yards. She stopped and stood looking at me, like I was the dumbest critter on earth. I swear she rolled her eyes like a teenage girl, and then ran back into the thick brush that had spit her out a moment before. The deer was gone before I could even think about the rifle hanging on my shoulder.

The dogs broke from the brush hot on her track. Bee Bee overran the track where the deer made the abrupt turn. She stopped at the wet spot on the ground, sniffed it a few times and looked at me as if to say, “You are one stupid Yankee.” Then with a doggy shrug, she picked up the deer track, let out a bawl and headed back into the jungle that passes for woods north of Baton Rouge, La.

That’s the thing about hunting with dogs: You can’t let your guard down for a second. The deer had gone around me, just like I thought, but it also ran into Scott just as he pulled into his stand near the edge of the property line. The deer decided that the only option was to charge back the way it came and take its chances. This happened so fast the deer was on me before I heard the dogs change direction.

The worst part was admitting to everybody at camp what had happened. I felt like a newbie, a rookie, like the guy even the dogs were laughing at.

With predictable Southern politeness, the crew at camp just brushed it off, but I knew none of them would have received the same treatment. I was a guest and Southern tradition dictates guests are treated with extreme graciousness. The members of this hunting club were all old friends who had been doing this dog-hunting thing for generations and no doubt would have been relentless on one of their own. That’s the same in deer camps any place in the country. If you mess up, your buddies will harass you unmercifully. If they screw up, they expect no less. It’s how they show their love. Like deer camps everywhere, there is a bonding with the members that is found in no other segment of modern society. As an outsider, a guest, I was exempt and that was fine; it’s what I expected.

The hunt was short, just a day and a half, and it left me with more longing than it satisfied my quest to experience this fading Southern tradition. But that’s what a good hunt does, it leaves you wanting more.

The sad thing is, with deer hunting with dogs in the South, “more” is a dying concept. Those who applaud its passing simply have not thought this thing through. If we lose dog hunting, we move a step closer to losing a part of what you hold close, too.

Family means looking out for one another. We hunters would do well to look at the close bonds these hunters share and realize we are all family.