When boar raccoons square off in mating-season battles each winter, their roars, growls and hisses could chase Hell’s demons from the woods.

But to other raccoons, those brawling boars must sound like can’t-miss TV, judging by how fast they scurry from warm den trees on cold days to watch, heckle or join the fight. Unfortunately for them, their eagerness dooms them if the sounds of battling boars are actually recorded calls played by rifle-toting hunters like Craig Polensky of Watertown, Wis.

Polensky, 45, has hunted and trapped woodlots near his home in southeastern Wisconsin all of his life during fall and winter. Like most hunters, however, he usually targeted deer, pheasants, waterfowl and other small game when hunting, and focused his raccoon “work” on trapping. After all, hunting raccoons with a scoped rifle is usually best at night when the masked, ring-tailed marauders are most active.

Unfortunately, if deer-hunting landowners or their friends believe nighttime coon hunting puts deer on high alert 24-7, they forbid hunting the night shift, too. Eventually, Polensky found a way to hunt coons in daylight by shifting most of his efforts to December, January and February when most hunters abandon the region’s woodlots. Once the firearm deer seasons end, and brutal cold persuades most bowhunters to forgo the late season, many properties closed to Polensky throughout autumn reopen as farmers and landowners welcome him to cull the coon population through any legal means.

He first experienced the wild excitement of calling coons after buying and wearing out a DVD by Iowa’s David and Mike Sells: “Cold Weather Daytime Raccoon Calling.”

The Sells’ coon-calling expertise is well-known among trappers and fur-trade folks, but most varmint hunters overlook these tactics. Why? Because varmint hunters are usually more interested in fox, coyotes and/or bobcats.

Polensky thinks that will change as more predator hunters learn how fun daytime coon-calling can be. And make no mistake: This tactic can offer nonstop excitement.

“The Sells are really good at sharing everything they know through their DVDs, but you still have to get out there, make mistakes and learn from your mistakes,” Polensky said. “That helps you understand their advice and appreciate their tactics.”

A Hard-Earned Triple

When Polensky took me along in late December 2013, he grew increasingly worried as the morning slipped by without a sight or sound of raccoons—battle-hungry or otherwise. But it wasn’t for want of den trees, fresh tracks or coon trails as we made three long hikes through foot-deep snow to distant woodlots. Each time, though, we returned empty-handed after nothing responded to his electronic game calls. And then, right after we hiked into a fourth woodlot around noon, Polensky zeroed in on a den tree in a woodlot behind an aging barn.

The site had everything he desired for daytime coon calling. A well-worn raccoon trail snaked through the snow from the old barn, ending just yards inside the woods at the foot of a large oak. Raccoon traffic up and down the oak had chipped and flaked bark from the tree trunk, indicating they were denning inside the tree’s rotting core. Even better, a hole 20 feet up the tree looked plenty large for raccoons.

And better yet, no snow framed the hole. “No snow in the hole means they’ve been going in and out,” Polensky said. “When I find a den hole two or three days after a snowstorm and snow’s still rimming the hole, I don’t bother calling. If a coon’s in there, it’s not coming out.”

This old oak, however, not only looked good, it had two other traits. “The hole’s facing south, and the tree’s still alive,” Polensky said.

Why’s that important?

“The most active den holes in winter face the sun,” he said. “That helps coons stay warm. Plus, living wood is dense. It blocks wind and holds heat better than dead wood. Wind can whistle right through dead wood. Dead trees hold coons in October and November, but they’re not as good from December to February.”

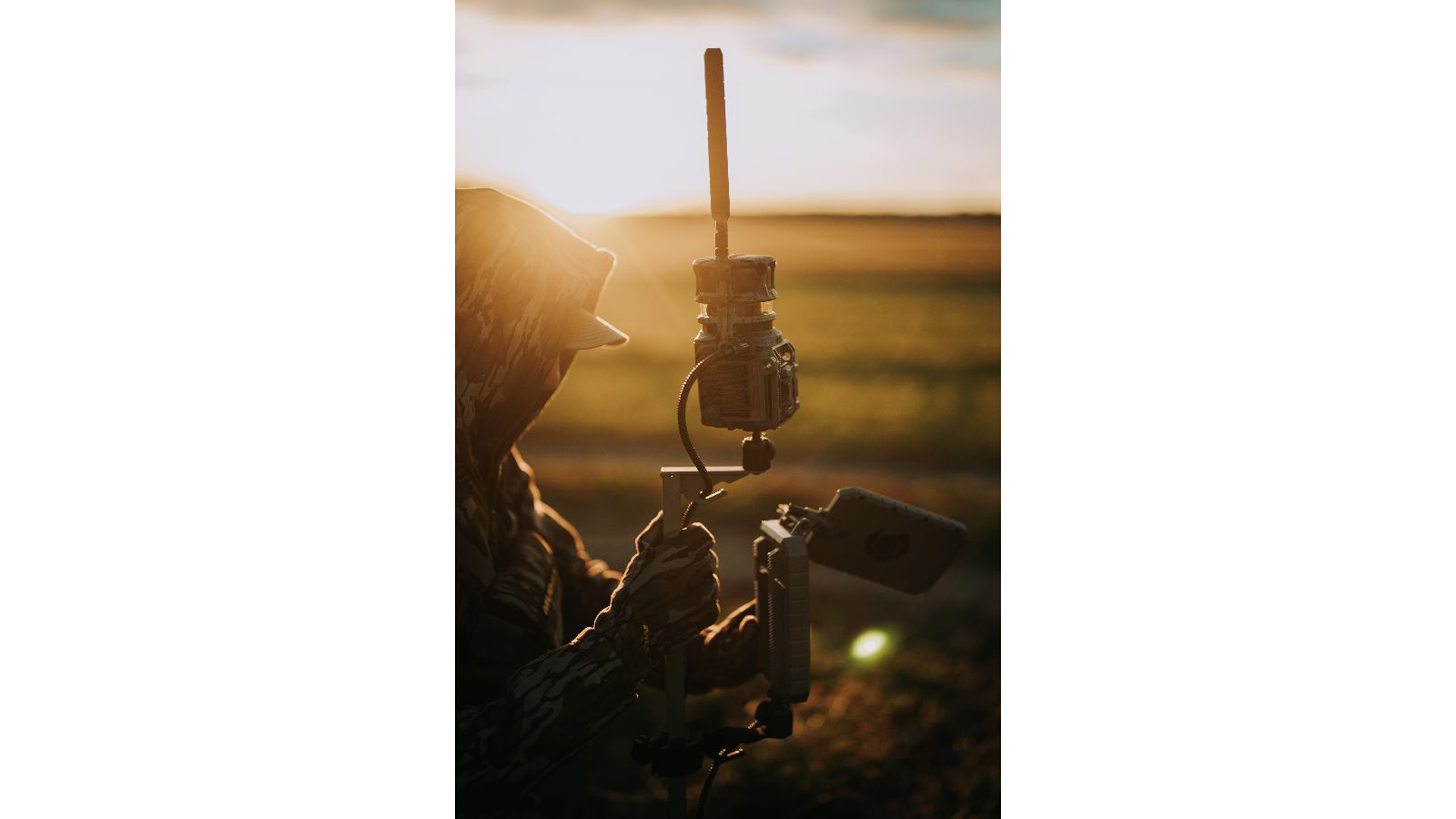

With that, he placed his electronic caller about 5 yards away on the opposite side of the tree from the den hole. Then we walked about 15 yards downwind from the oak, put about 10 yards between us, and hid behind trees the width of 5-gallon buckets.

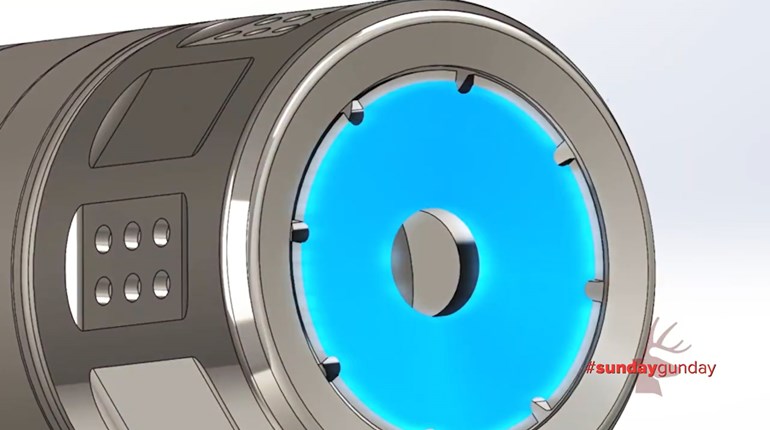

Polensky advised me to keep my camera poised to shoot as he did the same with his .22 Magnum lever-action Mossberg. He then pressed a button on his remote-control fob to activate the electronic caller. Even though I’d already heard the raccoon caterwaul several times that day, I jumped at the unearthly sounds.

Seconds later a raccoon burst from the oak’s den hole, looked around and started down the tree. I snapped photos as Polensky fired and cleanly killed the coon before it was 5 feet below the hole. It fell limply from the thick trunk and plopped into the snow.

I was about to congratulate Polensky when a second raccoon pushed itself from the hole and scrambled down the trunk, bark chipping off in its wake. A third coon followed closely behind. They hit the ground running and bounded through the snow toward Polensky. That was the last mistake they made. His .22 Mag. cracked four times, dropping both coons about 10 yards from the tips of his insulated boots.

Prime Pelts

“That’s the first triple I’ve ever gotten on coons,” Polensky said while admiring them and inspecting their pelts. He explained that raccoon fur hits its prime in early winter after growing thick and full to thwart the cold.

Even then, not all pelts achieve high quality. Raccoons that den inside old trees constantly rub against hard, rough edges inside the hole and the raspy bark at its entrance. Therefore, the pelts of tree-dwelling coons typically show some wear, especially when killed from late January to mid-February.

In contrast, coons that live inside brush piles or the cushy haylofts of old barns usually carry the best pelts. That’s because they usually find larger entryways in brush piles or the barns’ weathered walls, unlike with old trees where they must squeeze through tight, rough openings that wear down their fur.

Therefore, Polensky eyes every kill carefully to assess its fur quality. After he gets the coons home, he skins them and hangs their pelts in his garage, turning it into a crowded curing shed. He expects to receive $20 to $40 per pelt, depending on the fur markets.

He also guts the coons and stores their dressed carcasses in coolers for those who treasure the meat. He not only shares fresh coon flesh with friends, but also pastors and aid officials in nearby Milwaukee who help feed the homeless and other hungry people.

After explaining all that, he returns to more pressing matters: getting the dead coons out of the woods. It isn’t as easy as stuffing squirrels or rabbits into a game pouch and forgetting about them until returning to the truck. Polensky handles individual coons by slinging his rifle over a shoulder and carrying the coon by its hind legs. A double or triple, however, requires both hands and frequent rests, which inspires additional advice.

“Don’t forget to bring a little plastic sled,” Polensky said. “The farther you have to go, the more you’ll like a sled. These guys get really heavy, especially when you’re walking through a foot of snow.”

How heavy are they? “The ones around here average about 10 pounds, but the biggest one I’ve shot weighed 35 pounds,” he said.

Lining Up Woodlots

But to haul out coons consistently, hunters must first invest time, homework and lots of goodwill. For starters, run-and-gun coon hunting requires lots of land.

“It all comes down to finding as many dens as possible, spread over as many woodlots as you can hunt,” he said. “I talk to lots of landowners and hunt wherever they allow. Some of them don’t want you poking around their old barns or near their buildings, but others let you go wherever you can find a coon.

“It’s nice when you can just pull into a woods and walk right over to a den tree, but that’s the exception,” he continued. “You have to be willing to walk a ways, especially when it’s too muddy to drive in or the snow’s too deep to drive through.”

Having multiple sites also ensures you can hunt more than a couple of days. Most small woodlots only hold a handful of den trees, and your best chance will be the first time you hunt each new site.

“You can only hit each spot one to three times because coons get desensitized to calling,” Polensky said. “I figure I get about 50 to 60 percent of the coons to come out and look. If it’s a big woods with lots of dens, you can hunt it more often because they move around. But a small woods has only so many dens and coons don’t go far. If you don’t get them the first time, you might never get them.”

Weather conditions and lighting can also affect how often he hunts a woodlot. Polensky said raccoons usually respond better to calling on cloudy days with moderate temperatures, which means temperatures in the 20s and 30s for his region.

“Super-cold weather really shuts them down,” he said. “They’ll hole up during a cold snap and just not move. They usually don’t respond well on sunny days, either. If I think those factors kept them inactive, I’ll go back on a better day or a different time and try again. When it’s sunny, calling often works better late in the afternoon as the sun starts setting.”

Killer Setups

Size matters, too, in sizing up holes in den trees. “The bigger the hole, the better the chances a big coon is using it,” Polensky said. “And the more holes, the better the tree. Coons can’t fit through a squirrel hole, but they can get into some pretty small holes when they want. I’ve seen them struggle to get out when they want to fight, but just because they got into a hole doesn’t mean they’ll get back out of it. Sometimes they’ll give up and squirt out somewhere else on the tree, so you better stay alert.”

Once he determines a den tree has potential, Polensky takes no chances with his setup because raccoons won’t be fooled twice. He first identifies the hole that looks most heavily used, judging by wear and tear on surrounding bark. Next, he places the electronic caller where raccoons cannot see it from their hole. They pinpoint sounds precisely, and if they see nothing but a loud-screaming, suspicious-looking box, they’ll never come out.

After placing his caller 5 to 10 yards away on the tree’s opposite side, he hides off to the side where he can watch the hole without the coon catching his scent.

“Movement is the most important thing, so pick a big tree and get behind it,” he said. “If he sees you or the caller, it’s game over. Never set up directly in front of the hole. If you have to move your rifle, he’ll see it. Same thing with the wind. Coons have a great nose. They’ve busted me when I didn’t check the wind direction.”

Polensky prefers to wear camouflage, but it’s not as crucial as the setup. For instance, we hunted during a late-season firearm deer season, so we wore blaze-orange coats and hats to comply with state regulations. Even so, we didn’t worry. Raccoon retinas contain only one type of cone, which basically renders them color blind.

Conclusion

Once you’re in place and activate the electronic caller, keep your eyes and ears alert. In fact, Polensky suggests hunting in pairs, which means hunting with his wife whenever possible so they can cover all directions. After all, some den trees are so large it’s possible to overlook active holes.

And whatever you do, don’t assume your hunt is over after shooting the first coon that responds. “Multiple coons can come out of the same hole,” Polensky said. “If you see another one looking out after you shoot, it will likely come out. I’ve had a lot of them sit up there looking around for their partner, and then come charging out.”

Also, realize that coons could be denned farther away in trees you can’t watch simultaneously.

“You have to watch the ground around you because some coons will come running to the call from a long ways off,” Polensky said. “I’ve had my eyes glued to a den hole, and then had a coon come on a death run from the woods behind me. When they come in hissing and growling, looking for a fight, you’d better be ready. The sooner you hear ’em, the better the chance you’ll get ’em.”