I knew we were in good hands when Freddy broke out the pepper—not a shaker, but a pound of the stuff in a wide-mouthed container. He held it overhead and waved it through the smoke of our lunchtime fire before offering it to me.

“Want some for your kippers?” he joked. “Keeps the flies off ’em. Keeps flies off moose meat, too, but it’s not bad on kippers.”

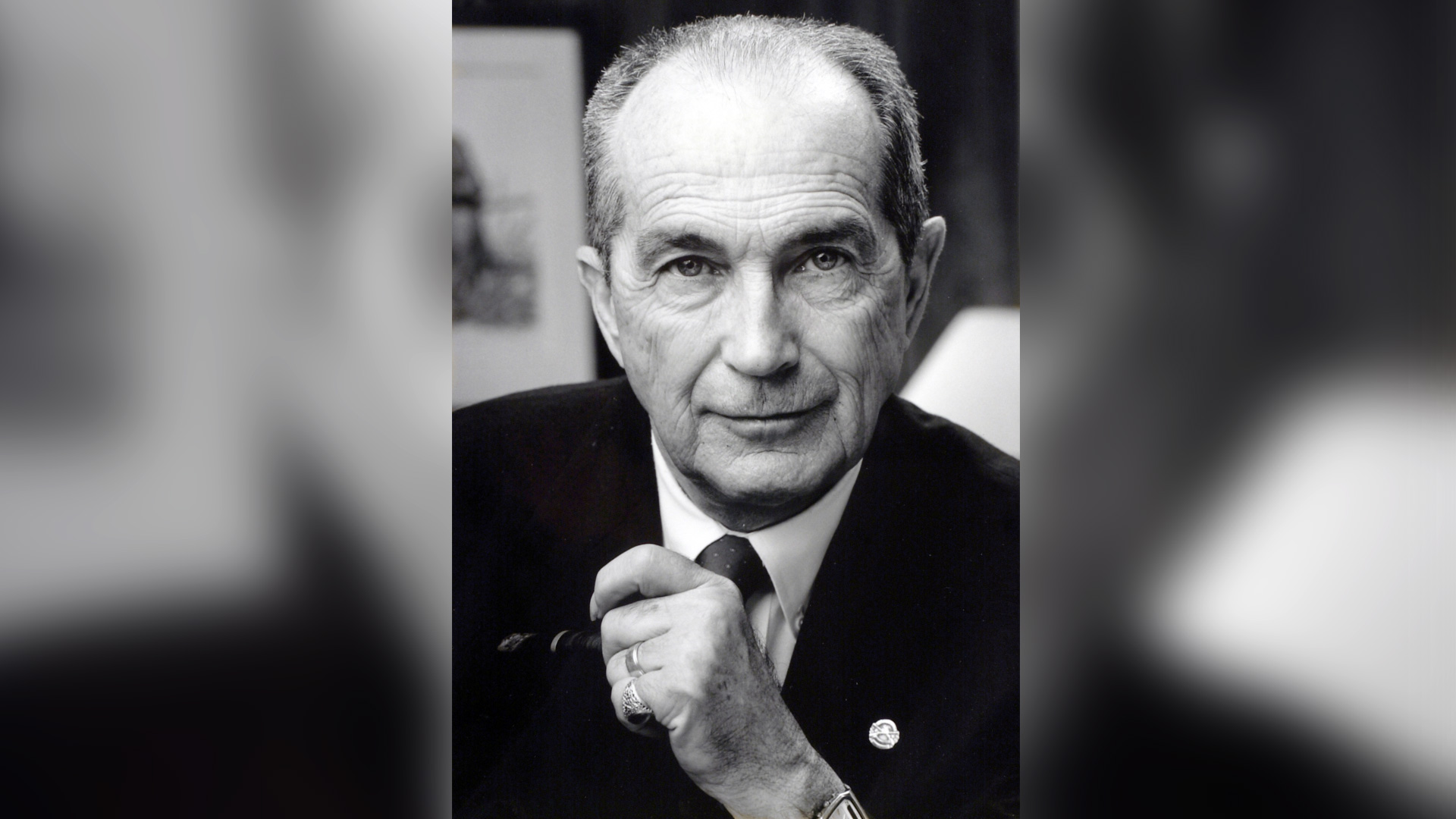

Freddy, 66 years old and tough enough to not care about an extra pound of pepper in his bulky pack, was clearly old-school. The best woodsmen usually are.

It had been raining steadily for a night and half a day, yet Freddy Youden and Derek Mollon, our moose guides, had needed only a few minutes before healthy flames were curling around the small pile of soggy spruce branches. On that dripping, dreary day in Newfoundland, both knew where to find the perfect tinder.

“It’s the pitch,” said Derek as he stuffed another wad of birch bark into the fire to help it along. “Best fire-starter around. Of course, you need to be in the birches to get it. I usually carry some with me in case I’m not.”

Freddy folded a few paper-like sheets of bark and shoved them in a pocket of his jacket. I peeled some from the birch I was leaning against and stowed it, too. When you see an old trick work as well as everyone claims, you make plans to use it the next chance you get.

The two guides and Danielle Sanville, my hunting partner from Thompson/Center Arms, skewered the kippered herring on sharpened twigs. I soon had Vienna sausages warming over the fire while my gloves and hat dried in the smoky heat. It’s true that food tastes better when you’re hungry, but it tastes best when you’re hungry and hunting. No pepper required.

We had been hiking and calling for moose since shortly after daybreak, following a timbered ridge that ran above an expanse of bogs broken by snarled patches of stunted spruce and fir trees known as tuckamore. Fog had kept most of the lowland shrouded from sight, but a brief late-morning break in the heavy gray air had allowed us a glimpse at a bull a half-mile below.

He appeared as a black rectangle that seemed to float above the yellow-tan grass of the bog. At first he was just movement; I caught the shifting of a shape through my binocular and studied it for long moments before I recognized it as a bull moose. When he turned his head, his light antlers broke the dark, boxy outline of his body.

“Bull down in the bog,” I said. “Look between the two tallest trees straight below us. He’s close to the one on the right.”

I kept my bino on the moose and heard shuffling as the others moved to find the view through the spruces. The slope below us was thick with timber, and we could see only small areas of the bog between the triangular treetops. I just happened to be glassing through the right hole at the right time.

“Looks like a nice bull,” Derek affirmed. “He has some long points.”

“Think he heard the call from down there?” I asked. It seemed far, and a crosswind blew along the ridge.

“He may have,” Derek replied as the bull disappeared behind the wall of spruces. “This sound carries a long way, and moose hear very well. Let’s sit for a while and we’ll call a little more.”

Derek’s moose call was a microphone-shaped speaker that played a recording of a bull grunt. It was a hollow, guttural “huh-whuh” sound that equated to bull moose trash talk. Being mid-September, the bulls were staking out their territories for the upcoming rut. The peak of breeding was a couple weeks away, and no bull would accept another bragging to the cows. While Derek played the call, Freddy whacked and thrashed nearby trees with a branch to mimic an egotistic bull tearing up the timber with his rack. Sometimes our resourceful guide used a plastic quart oilcan with its bottom cut off to scrape a tree trunk and simulate the sound of a bull rubbing his antlers.

Although the pair created quite a ruckus over the next hour, the bull didn’t reappear. With the fog and rain returning and the wind bringing a chill, Derek’s suggestion of a fire and some lunch sounded like a good idea. As we rested next to the flames eating kippers and sausages, I asked Freddy about the oilcan. I’d heard about using a canoe paddle to scrape trees and attract moose, but his homemade rig, with the spout of the can lashed to a short piece of axe handle for leverage via numerous wraps of electrical tape, seemed purpose-built for the job. The oilcan probably came from the supply used to maintain the generator back at camp. It was a notable example of backcountry ingenuity: Dozens of kilometers from the nearest road, our moose guides made the fullest use of what was available. There were no canoes in camp; this was strictly an overland hunt.

“A paddle works, but this is easier to carry and hold,” Freddy said. “Louder, too. Bulls make a lot of noise when they scrape.”

That afternoon Freddy’s oilcan saw plenty of use. We continued along the ridge, stopping every few hundred yards to scrape and call for 20-30 minutes. Seldom did the guides have to communicate to each other the strategy for a setup. They made an efficient team, but the bulls were unresponsive in the rain and increasing wind.

We climbed the ridge toward its end and topped out on a rolling plain covered in tall grass, tuckamore and hundreds of carnivorous pitcher plants. The water-filled vessels that the plants used to trap insects for food were turning scarlet with the coming fall. Although we were well above the bogs, the ground was saturated with water. It pooled in depressions that ranged in size from buckets to bathtubs, many of them hidden by the thigh-high grass. Walking across the spongy surface was difficult, but then Derek directed us toward a small piece of surveyor’s tape that marked a relatively solid trail back to camp. Years of crossing this top had shown him the best route, and he followed the trail with a precision no GPS could match. Having already sunk nearly up to my knees several times earlier in the day, I appreciated his knowledge with each firm step.

Our days started and ended in two large wall tents pitched on a wooden deck so their doors faced one another. The sides of the tents were fortified against the wind by 6-foot wooden walls, which also provided a backer for an assortment of screws, nails and hooks on which we hung our sodden clothing to dry. A camp stove in the corner of each tent put out more heat than we could handle if we didn’t keep it damped down.

One tent was our sleeping quarters and dining room, while the other housed the guides’ bunks and the kitchen. Next to the tents stood a large metal shipping container, which served as the camp’s pantry and supply closet. A third, smaller tent enclosed the toilet and shower facilities, the latter being hot water pumped from a 5-gallon bucket. Showers were an infrequent luxury, though, as the pump’s main duty was to supply the camp with drinking water from the brook that flowed beside the tents.

About 100 yards from the cluster of tents was another deck that served as a helipad—the key to the entire operation. Liverpool Camp, as our hunting base was known, is practically accessible only by air. Located near the western coast of Newfoundland at the southern end of the Long Range Mountains, and bordered by Gros Morne National Park to the east and north, the area contains no roads. The nearest two-track is a 20-minute helicopter ride over the mountains. From there, it’s an hour drive to the town of Corner Brook.

Shane Mollon, Derek’s son and the owner of Next Ridge Outfitters, contracted with a local helicopter service to bring in the supplies he needed to build the camp when he started hunting Liverpool Valley and the surrounding area eight years ago. At the end of the season Shane and his guides pack the tents and other large equipment such as stoves and mattresses inside the shipping container for the winter, which becomes buried under 8-10 feet of snow. The wooden structures remain in place from year to year (some requiring repair depending on winter’s severity), but the rest of the camp comes via helicopter throughout late summer and early fall.

Of course the arrival of supplies and hunters in camp during moose season is never a guarantee with the ever-changing Newfoundland weather. Wind and rain had nearly forced the pilot to ground his helicopter before the four hunters in our group made it to Liverpool.

The remoteness of the country and the planning it requires to hunt there keeps pressure on the moose low. In more accessible parts of Newfoundland, most hunters are satisfied with just about any bull. At Liverpool Camp, hunters look for bulls with a spread of at least 40 inches, wide palms and long points.

By the end of the second day, Danielle and I had passed on several small bulls—including two that Derek and Freddy called to within 50 yards. From the ridge we’d also spotted another big bull feeding in a bog and went after him. It took nearly an hour to descend the slope and break out of the timber, and once we lost the advantage of elevation it was difficult to tell where we were in relation to the bog in which we’d seen the bull. The tuckamore and lines of taller firs created a confusing maze. We climbed trees for a better look and soon spotted moose, but it was yet another small bull with a cow.

It was a long slog back to camp that afternoon, but our spirits were lifted by the return of the other two hunters in our group. Chuck Wahr from Trijicon and Eddie Stevenson from Driftwood Media crossed the footbridge to camp with smiles wide enough to see in the fading light.

They had spent the day on another ridge a few miles from camp with guide Chris Baldwin. A bull responded to Chris’ calls in mid-afternoon, and by waving the wide section of a canoe paddle over his head as a challenge, the guide brought the moose in close. Almost too close, said Chuck, as he took his shots at 20-30 yards.

The bull was a brute with a spread approaching 50 inches and broad slabs for palms that carried more than 20 points. We celebrated Chuck’s fortune, but not before he paused to remember a recently deceased co-worker who had planned to be on the hunt. Chuck said his only regret was that his friend wasn’t there to share in the moment. All of us in camp that night did our best to make up for the absence.

■■■

“If you think it’s bad going down, wait till we have to climb back up,” Chris said two mornings later as we slid through the mud, dodging rocks and deadfalls on our way to the bottom of a ravine. We were a couple miles from camp, and anticipation had us in a hurry. Chris knew where a big bull was hanging out. The day before as he, Chuck and Eddie were hiking back from quartering Chuck’s moose and preparing it for an airlift to the processor, they stopped for a break at the top of the ridge we’d just descended and glassed the face of the opposite hill. They spotted a bull worth pursuing, but it had been too late in the day to go after him. Chris was confident we could find the bull this morning, and he wanted to get over to that hillside as fast as we could manage.

Just as we approached the hill, the weather shut us down. Thick fog rolled in, and at times we could see no farther than a dozen yards.

“We’re going to have to wait this out,” said Chris. “That bull’s around here somewhere, and I’d hate to bump him. Let’s hold tight until this clears.”

A half-hour later the fog started to thin and we moved up the hill. Our first setup was on the edge of a small clearing surrounded by spruce and birch trees. Chris placed a remote speaker slightly downhill from us, and alternated between playing bull grunts and aggressively scraping trees with his sawed-off canoe paddle. The sounds carried along the hillside and echoed in the valley below.

“We want to make him think there’s another big bull on his hill,” explained Chris. “He’ll only be able to stand so much before he comes to take a look.”

We were trying to pick a fight with a 1,000-plus-pound animal. The thought occurred to me that I had been outmatched before when I taunted things bigger than my size. This bull seemed to be immune to insult, though. Our first calling sequence produced no response and neither did our second.

We were nearly at the top of the hill when we stopped for a third time, and it was almost noon. This spot was different in that we could see more than 200 yards of the hillside in front of us. Winter storms had smashed most of the timber flat. Several short, bushy spruce trees clustered in a rough circle about 15 feet in diameter made a perfect natural blind.

Twenty minutes passed with nothing showing up to Chris’ calls, and Eddie and I took a seat in the spruces to have lunch. I had just finished my sandwich when our guide pointed to his ear.

“A bull’s grunting back to us,” Chris whispered. “He’s over there in the trees on the other side of the clear spot. Get ready because when they grunt back, they’re coming.”

I made it to my feet and readied my rifle just in time to see the bull emerge from the timber, rocking his antlers in response to Chris’ calls. The rangefinder said 193 yards and I had a solid rest on shooting sticks, but the bull was closing the distance. I followed him with the crosshair as he swaggered down a little fold in the terrain, expecting him to emerge 50 yards closer. The dip in the hillside was deeper than I expected, though, and all that appeared seconds later were the tops of his palms.

He chose to remain in that fold the whole way across the hillside. I could see nothing in the scope but his antlers as the distance between us decreased to 100 yards … 75 … 50. This was a huge animal, 6 feet tall at the shoulder, and yet I had no shot. Seconds later he disappeared completely. I looked over the scope, baffled at where the moose could have gone. It was like the hillside swallowed him whole.

“Let’s go!” shouted Chris from behind me as he turned to run up the hill. “He spooked. He’s heading for the trees. Get to the top!”

As I sprinted toward the crest I saw the bull trotting up the adjacent hill. Chris blasted a cow call across the speaker, and I dropped to a knee. The bull paused broadside, looking back.

“He’s at 282,” said Eddie, training the rangefinder on the bull.

The moose took a few more long strides and stopped again. The crosshair floated across the upper half of his shoulder, I squeezed the trigger, and the bull fell.

We had lots of time to recount what had happened as we quartered the bull, bagged the meat and hung it in spruces for Shane and the helicopter pilot to pick up. Chris, standing slightly uphill from Eddie and me as the moose closed in, had seen it all unfold. His position had given him a clear view over the tops of the spruce trees that blocked the moose from my sight.

“I couldn’t understand why you weren’t shooting,” the guide said. “That bull was standing there on the other side of those spruces, 30 yards from you!”

We laughed at how I managed to turn a 30-yard shot into one more like 300. I was just glad the bull was a large target, a fact that became more obvious the longer we worked on the carcass. We finished the job by bagging the bull’s heart for packing back to camp.

On our last night in Liverpool Valley, Chris cubed the heart and sautéed it with onions. Danielle and Eddie had also taken bulls, and so the meal became a celebration of our success and a tribute to the game that had provided so much adventure during the week. It was delicious but needed just one thing. Freddy was happy to oblige with the pepper.