After two long nights of searching we are suddenly face to slimy face with our quarry, and if I don’t act fast, this probably won’t end well. The toothy predator is mostly hidden in the tall grass, lying in ambush like a lion, poised to launch an attack at nearly anything that will fit between its muscular jaws. Somehow it has permitted us to close within 10 feet of its lair, although this was certainly by chance as none of us were aware of its presence until seconds ago. There is little time to think about the shot, but as the tip of my middle finger kisses the corner of my mouth at the end of the draw, I hold just long enough to concentrate on a flattened forehead between two bulging black eyes.

The heavy fiberglass arrow punches through a yard of water and a couple millimeters of skull, and for a moment the bright white shaft vibrates with the shudder of death. I grab the heavy line attached to it and haul in the prize of the night, an unlikely trophy cloaked in mystery and feared by some for its voracious nature. The northern snakehead may be a fish, but hunting these finned invaders with a bow during the black of night offers a level of adventure rarely approached by mere angling.

“Watch those teeth!” shouts Capt. Bob Wetherald from the front of the boat. “They’ll cut you bad.” I take hold of the fish just behind its oversized maw and receive another warning: The gill covers are slicing sharp, too. Though the snakehead hangs limply on the arrow and I handle it gingerly, I still suffer a few cuts as I slip my index finger through its gills to free the fish from the shaft.

Blood and watery slime drip on the boat deck as I hoist the snakehead high amidst the glow of the lights surrounding the bow. Shaped like a torpedo with fins running more than half the length of its streamlined, camouflaged body, it is unlike any other fish I have ever boated and certainly an oddity to have skewered with an arrow. Field Editor Jeff Johnston, who set up this trip with Capt. Bob and quickly convinced me to shirk a deadline and join them, slaps me a wet high-five. The snakehead is about 30 inches long and weighs almost 8 pounds—a nice fish, but there are bigger ones here on the middle Potomac River bordering Maryland. Many of them, in fact. It is about an hour past midnight, and we have a few more hours to find them before we dock.

Blood and watery slime drip on the boat deck as I hoist the snakehead high amidst the glow of the lights surrounding the bow. Shaped like a torpedo with fins running more than half the length of its streamlined, camouflaged body, it is unlike any other fish I have ever boated and certainly an oddity to have skewered with an arrow. Field Editor Jeff Johnston, who set up this trip with Capt. Bob and quickly convinced me to shirk a deadline and join them, slaps me a wet high-five. The snakehead is about 30 inches long and weighs almost 8 pounds—a nice fish, but there are bigger ones here on the middle Potomac River bordering Maryland. Many of them, in fact. It is about an hour past midnight, and we have a few more hours to find them before we dock.

That we are bowfishing for snakeheads nearly within sight of our nation’s capital is an unexpected benefit of, and an answer to, the fish’s invasive habits. The northern snakehead is not native to Maryland; its homeland is China, Korea and Russia. How it got here is uncertain. Some point to releases by aquarium hobbyists when captive fish outgrew their tanks, but the Northern Snakehead Working Group of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service says importation of the snakehead for the live-food fish market is a more likely source of introduction. Snakeheads breathe air and can survive out of water for days as long as they are kept moist. Prior to 2002 and the prohibition of snakehead importation under the Lacey Act, tens of thousands were brought to the U.S. mainly from China and sold live at ethnic markets across the country, including those near Washington, D.C. The snakehead is regarded as a delicacy in Asia, and some cultures believe the fish has healing powers that are strongest if the soon-to-be meal is kept alive until just prior to cooking.

Whether snakeheads can heal the afflicted is questionable, but it’s certain they cause hurt. The northern snakehead is a ravenous predator, and it preys on many of the same forage fish that sustain the Potomac’s native species such as largemouth bass. Plus it eats other sport fish—a 30-incher will devour a 10-inch perch without thinking twice—and even makes an occasional meal out of a hapless frog or floundering baby duckling. Being an exotic, it has no natural predators here in the states.

But most concerning to biologists is the northern snakehead’s tenacity and prolific breeding, a combination that allows it to spread throughout watersheds like a plague. It’s a myth that the fish can “crawl” great distances across dry land, but it doesn’t need standing water to survive and can withstand temperatures as low as 32 degrees Fahrenheit. Females produce eggs up to five times a year and release as many as 51,000 eggs during a single spawn.

In 2002, an angler caught a snakehead from a pond in Crofton, Md., not far from the Potomac. Fearing the worst, biologists poisoned the pond and collected more than 1,200 snakeheads from it. Two years later, 20 snakeheads were pulled from the Potomac. The next year, more than 300 of them were taken from the same area. Now they are caught and shot by the thousands in the Potomac and its tributaries in Maryland and Virginia. Both states openly encourage anglers and bowfishers to target snakeheads and kill them on sight.

Captains Bob Wetherald and Jim Rice of Mid River Guide Service in Newburg tell me it’s nothing to shoot a dozen or more snakeheads in a night. Lifelong Chesapeake Bay waterfowlers and striped bass fishermen, the pair takes snakehead eradication efforts seriously but at the same time readily admits bowfishing for the ghastly foreigners is great sport.

“It’s an opportunity to hunt with a bow when most other seasons are closed,” says Capt. Bob. “This is more like hunting than fishing. You have to look hard into the vegetation to find them, and hitting them isn’t easy. It’s a challenge out here on the river at night, plus snakeheads really are good to eat.”

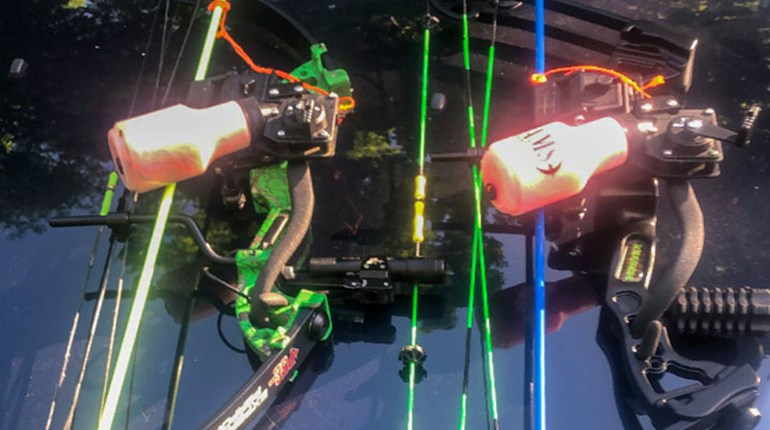

Captain Bob’s snakehead rig is an 18-foot SeaArk flat-bottom with a raised deck and nine 150-watt LEDs that illuminate a 30-foot half-circle of river to the front and sides of the boat. Shooting equipment includes PSE Mudd Dawg and Discovery compounds, and Kingfisher recurves, each set up with a reel or drum to manage and retrieve the thick nylon line attached to the arrow. There are no sights on the bows; aiming is either instinctive or accomplished by relating the barbed tip of the arrow to the fish. Shots come fast. Missing is expected.

We cruise the edges of the Potomac’s expansive weed beds in water 3 feet deep or less and marvel at the diversity of fish that dart through the light. It’s like looking into a giant, ever-changing aquarium. Although snakeheads are our main target, blue catfish—another species not native to the Potomac and therefore loathed in ecological circles—are also on the hit list. By the end of the night we’ve filled two Yeti 75 coolers with cats, some approaching 20 pounds. My fingertips are numb from pulling the bowstring.

We get but two more opportunities at snakeheads and make good on one of them. The northern snakehead seems much like the Eastern coyote: lurking in untold numbers though hardly a sure thing when the hunt is on. The thick, aquatic vegetation works against us to hide the snakeheads well on this mid-August night. Captain Bob says May and early June, when the hydrilla and submerged grasses are still short, is prime snakehead hunting. I remember this a couple days later as I feast on the filets from my fish—firm and mild, something like a cross between grouper and tilapia—and can’t wait until turkey season is over next spring.