“[The Tower’s] remarkable structure, its symmetry, and its prominence made it an unfailing object of wonder … once seen, so singular and unique that it can never be forgotten.”

—Henry Newton, Assistant Geologist, Newton-Jenney Expedition, 1875

Carlile, Wyo.—From afar this landscape appears dried and cracked, as if it could use some rain. This is the northern plains, after all; it never rains as much as it could around here. On the other hand, this northeast corner of Wyoming gets a little more moisture than the rest of the state. Closer inspection reveals thriving agriculture: wheat, alfalfa and barley, and plenty of cattle. And there are plenty of deer. We notice that the first morning as we glass a wheat field bordered by a hardwood creek bottom and note one, two, five specks feeding in the predawn darkness.

This is Black Hills country. The forested region lies mostly in South Dakota, but spills into Wyoming. That is significant to deer hunters looking for adventure because while the Black Hills clearly are mountains, their elevation never tops 7,200 feet. A lot of this country is rolling foothills covered with oak and ponderosa pine, and it abuts ranchland favored by whitetails. That’s right: oak trees. This corner of Wyoming is significant for that, too, for the whitetail likes acorns.

Once upon a time all anyone wanted to hunt in these parts was mule deer. In a state populated by elk, pronghorns, cougars (one was actually bagged during our hunt), bears and even bighorn sheep, the mule deer is symbolic of the West, and cheaper to hunt than elk or sheep. That all began to change in the 1980s when mule deer populations noticeably declined, and game managers were forced to reduce tag allotments for them. Attention shifted to the whitetail.

As we prowl ponderosa-covered hills later in the morning we note deer tracks, and I spy a cottontail hiding beneath a deadfall. Over my shoulder lies Devils Tower. Many, many generations of fauna have come and gone here since the monolithic landmark was formed. It’s true whitetails have roamed this region for as long as anyone can remember, but Devils Tower beats all comers in the age department.

Until last November, I’d seen the tower once but never entered the park created to preserve it and thus never learned its secrets. This time I determined to right that blight in my knowledge. Many stories exist to explain the tower’s origins.

There are at least three geological theories. Scientists agree on two points: the tower is composed of igneous rock, formed about 1.5 miles below the surface of the earth where magma pushed up through sedimentary rock layers about 50 million years ago; over millions of years, erosion stripped away the softer layers of sedimentary rock to expose the tower.

From there, three interpretations diverge. Perhaps the most well-known is the Volcanic Plug Interpretation. Regardless, at some point as magma cooled and solidified, it shrunk to form stress points. To release the stress, the rock cracked. These cracks grew outward from a central point in three directions at 120-degree angles. The cracks continued to grow outward and downward, intersecting with other cracks to form four-, five-, six- and even seven-sided columns; however, many cracks formed six-sided columns, the tightest and strongest fit nature can create. These symmetrical columns, the most unique feature of the tower besides its imminence, are the tallest and widest in the world. Some are taller than 600 feet and 10-20 feet wide. Over the eons, some have toppled onto the pines growing beneath them, to rest like ancient Greek or Roman ruins.

On top the tower is not flat as it appears from afar but rounded, and about the size of a football field. Folks who dare climb up there are greeted by woodrats, mice, ants and a snake or two.

The Black Hills and the tower have been a gathering place for many people for at least as long as 10,000 years, according to archeological discoveries. Arapaho, Cheyenne, Crow, Kiowa, Lakota and Shoshone people all developed cultural and spiritual connections to the tower. Today, they continue to hand down their beliefs to succeeding generations. Tower visitors may see prayer cloths or prayer bundles placed by Native Americans.

A Kiowa legend tells the story of a girl who acquired “bear medicine” then, while playing a game called “bear,” changed into a bear and killed everyone in a camp except her little sister. Their brothers returned from a hunt and helped the little sister escape, aided by the buffalo, a flat rock and a tree. The buffalo slowed the bear long enough for the children to reach the flat rock; the flat rock told them to go around it four times, and stand on top of it; the rock then grew from the ground. The bear could not reach the children, and raked the sides of the rock, gouging deep scars into it. Then a great tree told the children it would save them. Climb on me, it told the children, and it began to grow toward the sky. Thus the Kiowa tell the story of the Tso-i-e, the Rock Tree. Today in the night sky, the children are still pursued by the bear; look for seven stars (the Pleiades).

Clearly, the tower inspires everyone. Folks who have seen pictures of it may regard it only as a fascinating geological formation. Local inhabitants and tourists may appreciate its recreational opportunities. But among ancient cultures, the tower is a traditional and sacred site.

Several Native American languages refer to the tower as a bear’s dwelling. Besides Rock Tree, it is also called Bear Lodge, among other “bear” names. Thus in 1857, it was identified during the first scientific exploration here as Bear Lodge. Then, during his expedition of 1875, Col. Richard Dodge named it Devil’s Tower because, he reported, some Indian tribe called it Bad God’s Tower. The story is suspect, but Dodge’s moniker was widely disseminated about the time European-American emigrants were drawn here by reports of vast natural resources and unlimited land. Then surveyors used the name when they prepared the first official map of Wyoming in 1879.

William Rogers and Willard Ripley were the first to climb the tower, in 1893. They fashioned a crude, 350-foot-tall ladder by hammering stakes into a crack. By 1937, modern climbing techniques were employed, and today hundreds climb the tower annually. However, Native American culture disapproves of the act; to them, hammering pitons into the sides of the landmark is tantamount to dishonoring a place of worship. A plan asks for a voluntary cessation of climbing during June, a time of traditional cultural activities in the park, though not all climbers agree with it.

Perhaps the biggest stunt on the tower occurred in 1941, when George Hopkins parachuted to the summit to “prove that I can hit the impossible.” Well he hit it, and there he sat for six days before a party of technical climbers rescued him.

Photographers and painters accompanied many expeditions into the Black Hills in the 19th century. In 1876, many Americans first glimpsed the tower at the St. Louis Fair, where stereopticon photographs taken by the Newton Jenney Expedition of 1875 were displayed. William Henry Jackson’s photographs of the landmark, taken during an 1872 expedition, were displayed in 1893 at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Painter Thomas Moran displayed drawings of the tower he made during the same expedition in The Century magazine in 1894. At the same time, the tower became a popular gathering place of ranchers and homesteaders who settled here in the 1880s; folks traveled for miles to celebrate Independence Day here.

The Antiquities Act of 1906 called for the preservation of “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic and scientific importance,” and that very year President Theodore Roosevelt designated Devils Tower as a national monument. Coincidentally, the official government proclamation establishing Devils Tower unintentionally dropped the apostrophe, and the mistake was never corrected. With or without the apostrophe, many Native Americans oppose the name to this day based on its negative connotations.

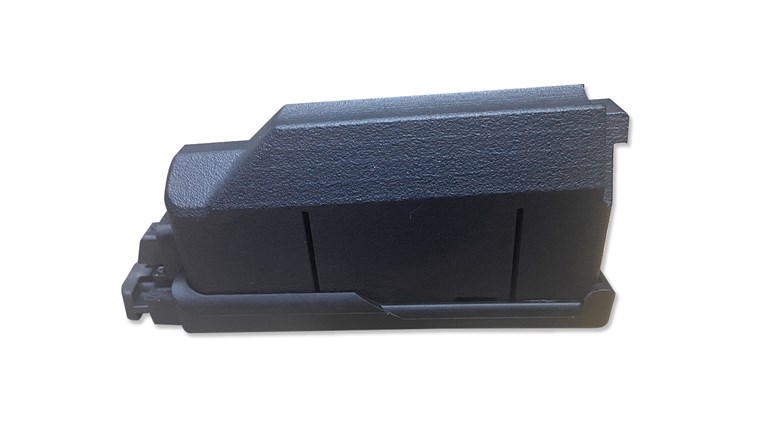

As I scan the landscape, I am reminded that like the whitetail, I am a newcomer here, at least in geologic terms. Like hunters of old, I am mesmerized by the flora, the fauna and the ever-present tower. However, today I am armed with a Browning Hell’s Canyon Speed bolt-action rifle in .30-06, a cartridge adopted by the U.S. Army the same year the tower was protected.

The whitetail continues to expand its range here. Ralph and Lenora Dampman of Trophy Ridge Outfitters know this, and so their guided hunts offer a chance at 130- to 160-class whitetails. (Indeed, one fellow in our party killed a genuine Booner.) To maintain high success rates, the Dampmans take only a limited number of deer from each property they hunt. Depending on the deer and the hunter, they spot-and-stalk in the mornings and stand-hunt in the afternoons.

I did that the first two days, but by now I’m tired of sitting in a box blind as the sun beats down on me. I think about what my guide told me last night: From afar, he’d glassed a big buck prowling the hillside above me; the critter stayed just out of my view. So as the sun sets, I decide to climb down and still-hunt, but not before the guide rolls up quietly in his ATV. “It’s up there again,” he hisses.

We make a plan, not without a problem, I learn later: I am wearing earplugs because the Hell’s Canyon Speed is fitted with a muzzle brake, and I just don’t want to subject my ears to the thunder of its blast. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

We don’t have to go far to find the buck; it and other deer amble in the setting sun about 500 yards uphill. We duck-walk and skulk to no avail—the deer spot us anyway. But they don’t run off harried. It seems they’ll come back if we hunker down and wait, a plan communicated between hunter and guide with hand signals and a little whispering. And indeed the buck does return—and again I just can’t get a shot. Time is getting short: Will the buck appear again? No, but it does stop long enough in a tree line on a bluff to survey the danger it has escaped, almost as if it has inherited a genetic trait from mule deer.

It’s all I need. With the rifle rested in the sticks before me, I quickly line up the reticle of the scope with a patch of brown on the buck’s shoulder and squeeze the trigger. My bullet travels a bit more than 200 yards to anchor the buck where it stands.

After the backslapping, the first thing my guide says is, “You know, there’s a bigger buck up there.”

“What?” I ask. “You mean … ”

Then it occurs to me that the first buck we’d seen was indeed bigger than this fella. Clearly, some of the whispers were muffled too much by the plugs in my ears ... I’d become confused—I’d shot a smaller buck.

I think about that for about five seconds then brush it off. And as we line up a trophy shot with Devils Tower behind me, I resolve that shooting a “lesser” buck really doesn’t matter in the grand scheme of things. This land has been hunted for 10,000 years. I’m sure my deer isn’t the first case of ground shrinkage experienced in the shadow of such an immense presence.