Moments of self-reflection tend to be disappointing and therefore do not occupy a place in my regular routine. They are not missed. I have managed just fine without them for a very long time and quite honestly see no reason to change. That noted, I must begrudgingly admit to having learned something about myself recently, although most certainly by accident. Since a similar circumstance likely applies to other hunters, at least to some degree, this discovery seems worth mentioning.

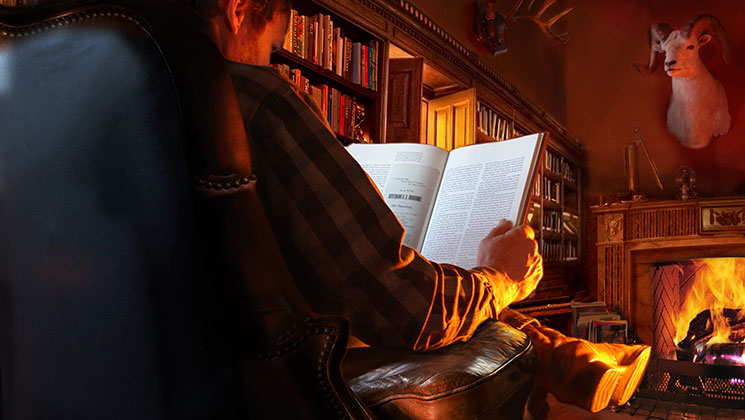

Here’s what happened. A well-traveled hunter stopped by for dinner. While we have known each other for upwards of 30 years and shared nearly a dozen adventures across North America and Africa, he had never been a guest in my home. We got caught up while looking at some trophies and a couple of interesting rifles, then settled in for dinner. Sometime during dessert, the conversation landed on favorite hunting books and we passed the balance of the evening in front of the library cabinet. After he left, I realized that we had discussed books with more enthusiasm and passion than any other subject.

I spent much of the following day pondering just exactly what role books seemed to have played in shaping our interests in hunting. We had both become avid readers while very young. Even though our fathers were primarily bird hunters, if only by circumstance, each of us had maintained an unwavering focus on big game and selected our books accordingly. Finally, as opportunities to participate in big-game hunts did not begin until well into our teens, we both had read continually to keep the fire burning.

Although the desire to hunt is certainly inborn, I couldn’t help but wonder if hunting would have become the driving force in our lives if not for reading about it with such dedication at a young age. Would this desire have become so intense without the continual excitement books provided as we grew older? Might we have focused on another activity with equal enthusiasm absent the matronly librarians who stocked the shelves with appealing titles? Could it be that 799.26, the Dewey Decimal System call number that runs like graffiti along the spines of big-game hunting books, represents something as important to the development of a hunter as predisposition, encouragement or even opportunity?

I was captivated by the idea of hunting big game, and in particular Africa’s dangerous game, long before my first day of kindergarten. Since I could not legally hunt birds until 12 and deer before turning 14, and did not even manage to kill a deer until 18, why didn’t the dream fade? My father never encouraged me to plan for Africa, or for that matter even to hunt the great game of North America. Rather, he cautioned that I not “get my hopes up” in order to dodge disappointment if it didn’t come to pass. Instead, we chased birds together every possible day each fall, and he bought BBs and .22 LR ammunition for me with such frequency that the local hardware store offered to give him a private express lane. Always I was reading, and I’m pretty sure that is the reason hunting occupies such an important part of my life.

I was captivated by the idea of hunting big game, and in particular Africa’s dangerous game, long before my first day of kindergarten. Since I could not legally hunt birds until 12 and deer before turning 14, and did not even manage to kill a deer until 18, why didn’t the dream fade? My father never encouraged me to plan for Africa, or for that matter even to hunt the great game of North America. Rather, he cautioned that I not “get my hopes up” in order to dodge disappointment if it didn’t come to pass. Instead, we chased birds together every possible day each fall, and he bought BBs and .22 LR ammunition for me with such frequency that the local hardware store offered to give him a private express lane. Always I was reading, and I’m pretty sure that is the reason hunting occupies such an important part of my life.

All this really isn’t much of a stretch if you think about it. There is no greater adventure to be imagined than hunting man-eating tigers as described by Jim Corbett in Man-Eaters of Kumaon, of calling in the massive Bachelor of Powalgarh or killing the Chowgarh tigress at a distance of 8 feet. Even Marilyn Monroe kept a copy of this book in her collection. I twice tried to buy it at auction, but all things Marilyn command a great price. In retrospect, I should have kept bidding. My daughter’s teeth weren’t all that crooked.

If Corbett’s tale has an equal, it would probably be Patterson’s quest for the pair of lions who stopped the construction of a railroad as related in the first portion of Man-Eaters of Tsavo and Other African Adventures. After reading Corbett and Patterson tirelessly as a boy, is it any wonder that I became a hunter?

I made it to Alaska several times before finally touching down in Africa, a chronology that speaks to the influence of Russell Annabel. His ability to tell a story shot through with thrills, humor and hardship makes for some of the finest hunting books ever published. He is probably most famous for Tales of a Big Game Guide, but his Alaskan Tales is the better book. A wonderfully inscribed copy of the latter is the centerpiece of my library today, and I still remember the glare of a grade-school teacher when I suggested Annabel’s often-used “cheechako” and “siwash” should be considered for extra credit on an upcoming spelling test. The impact of his words has even taken a tangible form in my family. My son likes his writing so much that my granddaughter’s name is Annabel.

It’s mostly the fault of Jack O’Connor that I love fine rifles and costly sheep hunts. He also finished what Russell Annabel started when it came to grizzly bears and moose, and along the way made me realize that there were things in the Southwest and Mexico worth hunting. My interest in ballistics and appreciation of trophy quality, that’s all from Jack. His Sheep and Sheep Hunting is certainly among the finest books ever penned in celebration of mountain game.

Finally, there’s Buster. If Robert Ruark is the poor man’s Hemingway then I’m indeed a poor man. Proud of it, too. I read Ruark until the pages were tattered and latticed with so much yellowing tape that the covers bulged in the middle, all the while imagining myself the Old Man’s boy. Ruark came from humble stock, more or less, and managed to find adventure within walking distance. That rang true. Even his hometown seemed similar to mine, sort of a Mayberry with guns where the good boys barefooted down Main Street on their way to fish the lake and the delinquents peddled out past the town limits to hold their dirt-clod fights. Ruark worked hard, got heeled and flew off to Africa, then he came back and wrote the finest book anyone ever wrote or ever will write about hunting or anything else for that matter. Nothing approximates Horn of the Hunter, although the very best of Ruark might appear in the final pages of Use Enough Gun where he masterfully describes shooting an old elephant bull and the collision of emotions that followed.

There were other authors. Bell, Taylor, Hunter and Selous painted vivid pictures of the old Africa that was already 50 years gone by the time I discovered their tales. More contemporary stories by Page, Jobson and Gresham sent me rushing to the world map as if placing a finger on the spot of their latest adventure would somehow take me there so I could experience it for myself.

Books are one of the primary reasons I became a hunter, and a whole bunch of others will probably admit to the same thing if they let their guard down long enough to consider how much reading influenced their interest. In this case it may even prompt a visit to the library, which someone given over to puns might suggest is long overdue. Remember, the hunter’s number is 799.26. Seeing it again is a wonderful homecoming.