This much I knew: Somewhere above me, among the broad, green and yellow leaves of a towering hickory, there was a squirrel. The unmistakable sound of incisors grating against nutshell left no doubt. But whether I would see that squirrel, or get a shot, or hit the tiny target in the treetop was greatly uncertain.

Stock-still I stood, head sharply tilted back, eyes focused upward, arm muscles quivering from the weight of the gun or anticipation or both. The game was just a squirrel, but for 10 minutes while I awaited the gray's next move, hunting was as good as it gets.

Allowing my neck a brief rest, I lowered my head to glance at the rifle and considered my odds. I could have taken a shotgun on that overcast morning in mid-September, or a .22 with a scope. Either one would have improved my chances of adding squirrels to the pot later that night, but the way in which I hunt often means more to me than the outcome. I didn't step into the woods at first light to kill squirrels as much as hunt them, in a way that would both challenge my skills and reward only my best efforts.

Thus, my firearm of choice was a .36-caliber flintlock, a Shenandoah rifle from Traditions Firearms. With both game and gun, I was returning to my roots. Squirrels were one of the first things I hunted as a boy, and flintlocks were among the first rifles carried by pioneer woodsmen in the mid-1700s. Standing in the creek bottom that morning, waiting for the squirrel to show itself and give me a shot, I couldn't help but wonder if one of my ancestors had done the same thing in the same spot more than 250 years before.

A rustle in the leaves overhead followed by the ticking of claws on hickory bark interrupted my thoughts. The squirrel had decided to descend the trunk, where few leaves hid its movements, and things were about to get interesting. I slowly raised the long-rifle while thumbing back the hammer, and the crescent-shaped buttstock nestled tightly against my shoulder. When the squirrel paused on a branch, I curled my finger around the set trigger until it clicked, readying the front trigger for release at the slightest pressure.

I was keenly aware of how steadily the rifle's sights settled on the squirrel and realized, again, why frontiersmen so loved the long barrel. With the gun's front brass blade precisely centered in the rear-sight notch and aimed at the squirrel's head just below its ear, I touched the front trigger.

Flint scraped frizzen, a shower of sparks fell into the priming pan, and my world became a cloud of smoke. Through it I caught a glimpse of the squirrel spinning backward off the branch, the hit confirmed by a dull thud as its body fell to the base of the tree.

Smallbore muzzleloaders or "squirrel guns" put a lot of meat on the table back when the only economical place to get a meal was from the woods.

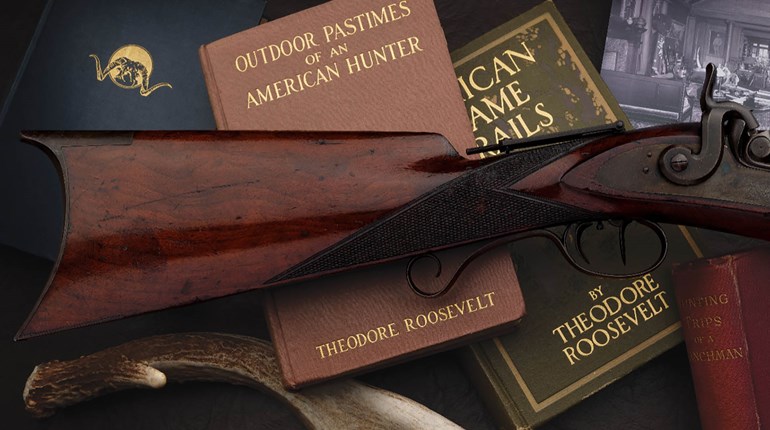

The slim, graceful lines of the Traditions Shenandoah rifle are reminiscent of those that defined the Pennsylvania-style rifles made in early America. Some smokepole scholars will point out that the Shenandoah is made in Spain, and that its 33.5-inch barrel is a bit shorter than typically found on classic Pennsylvania rifles, but the rest of its design hits the mark.

Running the entire length of the octagonal barrel, the Shenandoah's hardwood stock is embellished by several brass inlays, including a hinged patch box on its right side. Brass also highlights the buttplate, trigger guard, ramrod thimbles and fore-end tip. Purists may scoff at the aluminum ramrod, but in truth it's less likely to break than one made of hickory.

With a 1:48-inch twist, the .36-caliber barrel is perfect for patched roundballs. The barrel fits the stock tightly and may require a few taps with a rubber mallet to free it for cleaning. But first, remember to drift out the two pins and remove the tang bolt holding the barrel in place.

Delivering a ball to a squirrel's head-the only place a self-respecting muzzleloader marksman should shoot-requires a fine set of sights and a light trigger. The Shenandoah rifle has both.

Although the wings of the buckhorn-style rear sight may block out the majority of a furred target's body, the open area between them is plenty large enough to see the sweet spot. The square notch below the wings is just wide enough to allow a bit of light around the fin-shaped front blade, helping you make sure it's centered for the shot. Elevation adjustments to the rear sight come by way of a stepped ramp. Slide the sight up the ramp to move the point of impact higher. The front sight is dovetailed into the barrel; drifting it to the right or left adjusts windage. It can be a bit difficult to discern the front sight's brassy color against a squirrel in the shadows, but a dab of white fingernail polish will fix that.

The double-set trigger came from the factory just the way I like it on a flintlock-almost too light. Pulling the rear trigger sets the front to break crisply at a pull weight of 6 ounces. There are many variables when shooting a flintlock, and the trigger should not be one of them. I want the hammer to drop immediately when I command it. Nevertheless, the trigger is adjustable for a heavier pull weight.

If you'd prefer your squirrel gun be percussion instead of flintlock, Traditions offers the Shenandoah rifle in both. The hammer, sideplate and priming pan of the Shenandoah I hunted with is color-casehardened. The spring that powers the hammer is stout, and the sparks really fly when the flint hits the frizzen-after the mandatory flint adjustments, of course.

Even a traditional gun dedicated to squirrel hunting must be accurate, and I'm sure the Shenandoah rifle would get Davy Crockett's approval. When I did my part, shooting from a rest at 25 yards, three of the roundballs formed neat little clusters in an area smaller than a golf ball. On four occasions, the Shenandoah sent back-to-back balls through nearly the same hole!

Small-caliber flintlocks will probably never regain the popularity they held among the squirrel hunters of the past. But those of us who like to slip back in time and do things the old way can find a willing partner in the Traditions Shenandoah rifle. Just keep your eyes in the treetops and your powder dry.

860-388-4656

www.traditionsfirearms.com

Type: flintlock (tested) or percussion muzzleloader

Caliber: .36 (tested); .50

Barrel: 33.5"; octagonal; 1:48" twist (.36 caliber), 1:66" twist (.50 caliber)

Trigger: double-set; 6 oz. pull

Sights: elevation-adjustable, buckhorn-style rear; brass, blade-type front

Safety: half-cock

Stock: hardwood; length of pull: 131/16"

Overall Length: 49.5"

Weight: 7 lbs., 3 ozs.

MSRP: $551 (caplock); $618 (flintlock)